pain management

- related: Medicine

- tags: #literature

1. Assess Pain

- Using functional status as a guide

- 30% improvement as function

Types of pain:

- acute vs chronic

- malignant vs non-malignant pain

- Somatic

- tissue damage, muscle, bone

- aching, deep, dull, sharp, stabbing

- localized

- Visceral

- gallbladder, intestines, liver

- crampy, pressure, bloating, nausea, vomiting, sweating

- referred

- Neuropathic

- cause: somatic/visceral coexisting, injury of nerves

- electric, shooting, radiating, burning

- radicular, stocking-glove

- Opioid Risk tool: highest risk factors for substance abuse

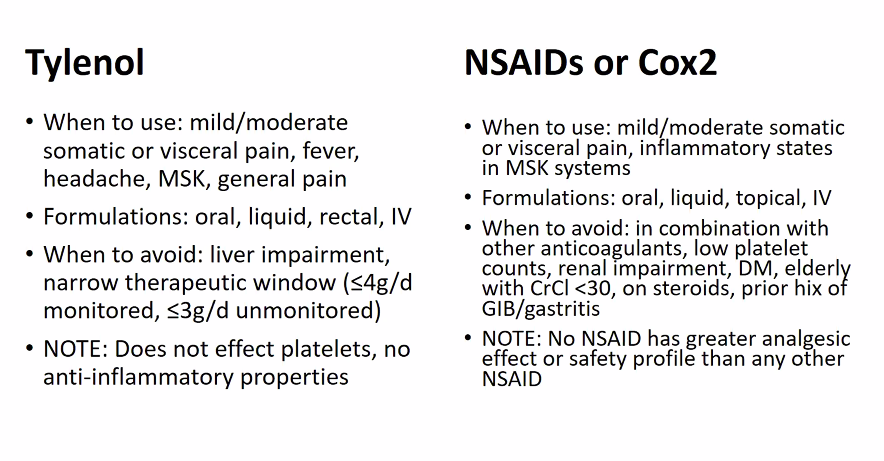

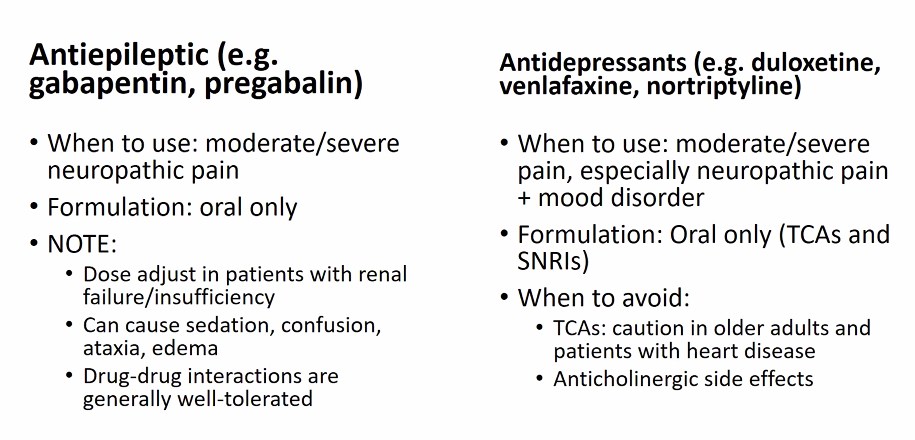

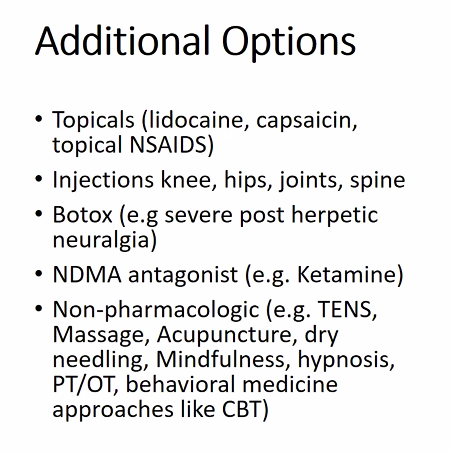

2. Match treatment to pain

Naproxen: 500mg PO BID, unless AA, can increase BP

Tylenol: 1g TID scheduled

Opioids

- PEG scale use for opioids

- chronic nonmalignant: no more than 50 OME/day (oral mili equavalents)

Side Effects

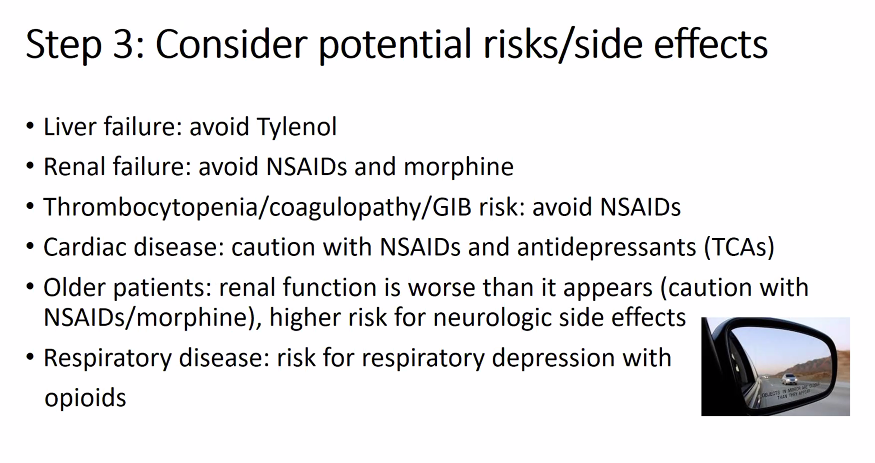

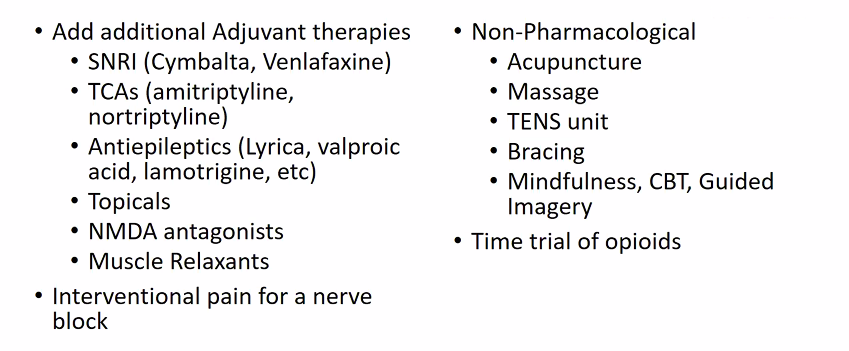

Additional treatment:

Muscle relaxant: use occasionally

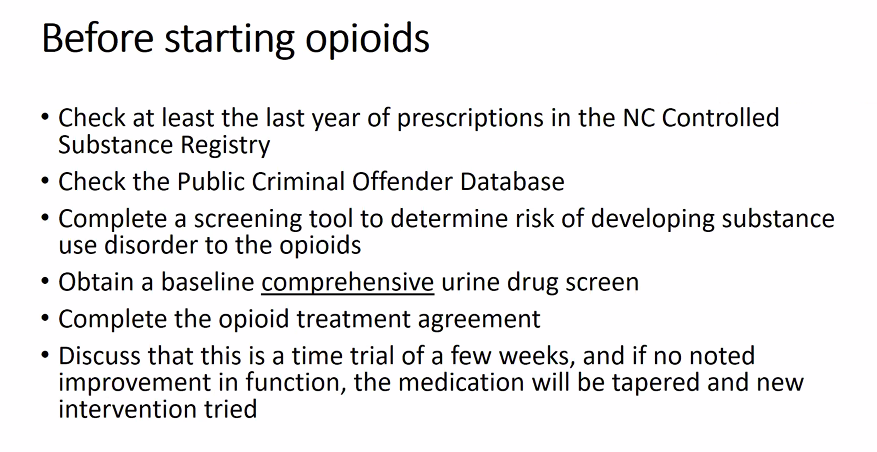

Before starting Opioids

- Do not use opiods and benzos. 10x mortality risks

The standard opiate screens on most commercially available urine drug tests, also known as opiate immunoassays, use morphine to calibrate a positive result. Here’s how various opioids fare on standard urine drug tests:

- The naturally occurring opioid morphine tests positive.

- Synthetic opioids, such as methadone and fentanyl, test negative, as does the semisynthetic opioid buprenorphine.

- The naturally occurring opioid codeine and the semisynthetic opioid heroin are both eventually metabolized to morphine and thus test positive on an opiate screen.

- Oxycodone, a semisynthetic opioid that breaks down into oxymorphone, frequently tests negative at lower concentrations but can test positive at higher concentrations.

In patients taking synthetic opioids or the semisynthetic opioid buprenorphine, the results of an opiate immunoassay do not provide an accurate indication of whether the patient has the drug in their system. A negative result cannot be interpreted as as an indication that the patient is not taking their opioid medication or as a suggestion of a mislabeled or switched urine specimen. If testing for buprenorphine, methadone, or fentanyl is indicated, then specific tests for each of these substances should be ordered.

G tube

Choosing an Alternative ER/LA Opioid The only available ER/LA opioid options to consider in patients with a gastrostomy tube are:

- Methadone via the tube (in crushed tablet or liquid form)

- A fentanyl or buprenorphine patch

- Specific ER formulations of morphine and oxycodone that come as capsules containing pellets; these capsules can be opened, and the pellets can be sprinkled in water and injected via the gastrostomy tube

ER oxymorphone tablets should not be crushed and are therefore not an option. Doing so would disrupt the extended-release formulation, potentially leading to rapid release and the absorption of a potentially fatal dose of oxymorphone.

Although methadone would be a reasonable analgesic to consider for this patient in either crushed tablet or liquid form, it is not recommended in patients who have a corrected QT interval 2500 msec and thus would not be appropriate for this patient.

Of the answer options listed, a transdermal fentanyl patch is the safest and most effective ER/LA opioid for this patient.

Fentanyl patch

How the Patch Works

The transdermal fentanyl patch is changed every 72 hours and consists of a reservoir containing the drug, a rate-limiting membrane through which the fentanyl can diffuse out of the patch, and an adhesive allowing the patch to be placed on the skin. This design allows the release of fentanyl at a near-constant rate into the subcutaneous fat from which it can reach systemic circulation.

Serum fentanyl levels reach a relatively steady concentration 12 to 24 hours after initial application of the patch; when the patch is removed, the levels fall slowly, with a mean 50% decline 17 hours after removal.

Absorption of fentanyl may be diminished in patients with cachexia and anasarca. Of note, fentanyl concentrations are higher in patients taking cytochrome P-450 inhibitors. In addition, increased body temperature can cause increased absorption of the drug, so the patch should be avoided in patients who have high fevers or are using hot tubs or heating blankets.

More buprenorphine

Buprenorphine as an Analgesic

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist and, as such, is associated with a lower risk of severe respiratory depression than full opioid agonists, such as morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, methadone, and hydromorphone. Thus, it has a niche use as an analgesic among patients with chronic pain who are at high risk for respiratory depression based on risk factors such as sleep apnea or their RIOSORD score.

Formulations and Dosing of Buprenorphine for Pain Buprenorphine for pain management is available in two extended-release formulations: a transdermal patch and a buccal film. The transdermal patch is changed every 7 days, whereas the buccal film is applied every 12 to 24 hours. Both are available in a range of doses.

Neither formulation is appropriate as a replacement opioid in patients already taking extremely high daily doses of opioids (>80 morphine milligram equivalents [MMEs] for the patch and 60 MMEs for the buccal film).

In patients whose opioid dose is 30-80 MMEs (patch) or 30—160 MMEs (buccal film), the total daily dose of opioids should be tapered to s30 MMEs daily before switching to the buprenorphine patch or film. This is because buprenorphine preferentially displaces full agonists from the mu opioid receptor and can therefore precipitate opioid withdrawal in patients who are receiving 230 MMEs daily.

Methadone

When a patient taking extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioids for chronic pain requires opioid analgesia for severe acute pain, the ER/LA opioid should be continued, and a short-acting agent can be added temporarily to cover the acute pain that is not responding to conservative therapies, such as nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen.

This particular patient could reasonably have oxycodone added to his regimen at a dose of 5 mg to be taken as frequently as every 4 hours as needed. Although a 5-mg dose may be too low given his opioid tolerance, it is a reasonable starting dose; if there is lack of benefit and no evidence of sedation, it can be quickly increased to 10 mg on the next dose.

Short-acting opioids generally last 3 to 4 hours, so dosing oxycodone only once every 12 hours would probably not provide sufficient pain control between doses.

The prescription for oxycodone should provide the patient with only enough medication to control his pain for a few days. Most causes of acute pain will resolve within that time frame; thus, providing individual patients with only a limited supply of opioids will help treat their pain while reducing the potential for diversion of excess opioids. Prescribing a 30-day supply is therefore not indicated. This patient has a follow-up appointment scheduled with an orthopedic surgeon in 3 days, at which time the patient and the surgeon can determine how best to continue with pain control.

The patient’s current methadone dosing (three times daily) is typical for the treatment of chronic severe pain (whereas once daily is typical for

treatment of opioid use disorder). Methadone has a long and variable half-life and can be difficult to dose for the management of acute pain without the risk of overdose. Short-acting opioids are therefore a safer option to manage this patient’s acute pain.

Given the significant potency of methadone and its long duration of effect, this patient is unlikely to experience adequate and sustained relief of both his acute and chronic pain (the latter of which was well controlled by the methadone) by replacing his methadone with short-acting opioid monotherapy.

Prescribing Opioid Analgesics in Combination with Buprenorphine Therapy for OUD

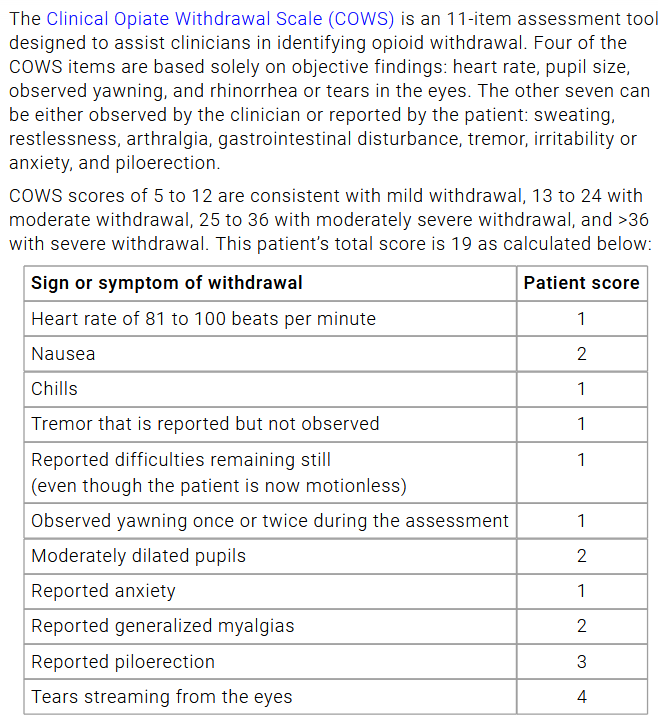

Withdrawal