Adult Congenital Heart Disease

- related: Cardiology and Hemodynamics

- tags: #cardiology

Introduction

Medical and surgical advances have resulted in more adults living with congenital heart disease (CHD) than children with these conditions in North America. All patients with repaired congenital cardiac defects require regular follow-up, specialized screening, and preventive care.

Women with CHD should be provided with reproductive health counseling. The use of contraceptive agents in women with CHD must be balanced against the risks of pregnancy; however, there are no safety data on the various contraceptives to help guide choice. Estrogen-containing contraceptives may pose a risk in women with CHD who are already at high risk for venous thromboembolic disease, including patients with cyanosis, Fontan physiology, mechanical valves, prior thrombotic events, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. In pregnant patients, anticoagulation is associated with maternal risks, including bleeding and thrombosis as well as fetal loss, and in the case of warfarin, teratogenicity. Prepregnancy counseling is recommended for all women requiring long-term anticoagulation to enable them to make informed decisions and to understand the maternal and fetal risks. Women with mechanical valves should be treated according to current guidelines (see Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease).

Adults with CHD are at risk for hepatitis C due to blood exposure during cardiac surgery. Screening for hepatitis C is particularly relevant in those exposed to blood products before universal blood screening was instituted in 1992. Hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for all nonimmune patients at high risk for infection, including patients with repaired CHD.

Anxiety and depression are prevalent but underrecognized in patients with CHD, and screening for these mood disorders should be a routine aspect of care.

In addition to a primary care provider, patients should have an adult congenital heart disease team. Regular care with specialists in adult congenital heart disease is critical for patients born with complex and cyanotic congenital cardiac disease, symptomatic patients, and patients who desire pregnancy. The frequency of follow-up depends on the underlying disorder and patient’s status.

The 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Guideline for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease introduced a new anatomic and physiologic classification system (http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/accj/early/2018/08/09/j.jacc.2018.08.1029.full.pdf). The new classification system is better able to capture issues related to prognosis, management, and quality of life.

Patent Foramen Ovale

The foramen ovale is a passage in the superior portion of the fossa ovalis that allows oxygenated placental blood to transfer to the fetal circulation. It normally closes within the first weeks of life; however, in 25% to 30% of the population, it remains patent (Figure 35). A patent foramen ovale (PFO) is usually found incidentally on echocardiography or during evaluation for a cerebrovascular event.

A PFO is typically diagnosed by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), less commonly by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). Right-to-left shunting of blood across the PFO is demonstrated by color flow Doppler imaging or by using intravenously injected agitated saline and identifying subsequent transfer of the agitated saline through the PFO from the right atrium to the left atrium. No treatment or follow-up is needed in asymptomatic patients with an incidentally detected PFO.

Management of patients with a PFO and cryptogenic stroke has been controversial. Antiplatelet therapy has traditionally been used as first-line therapy; however, percutaneous PFO closure has been shown to be of benefit in the prevention of a second stroke in selected patients. Current guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology recommend PFO closure for patients younger than 60 years with a PFO and embolic stroke of unknown source. Data regarding benefit of PFO closure in patients older than 60 years are lacking. For these patients, and for younger patients who do not select PFO closure, antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation is reasonable. Limited data support PFO closure in an effort to decrease the frequency of migraine. No treatment or follow-up is needed in asymptomatic patients with an incidentally detected PFO.

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is a rare acquired disorder characterized by cyanosis and dyspnea in the upright position as a result of right-to-left shunting across a PFO or, less commonly, through an atrial septal defect. A transient increase in right atrial pressure or change in right atrial anatomy resulting from myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, tricuspid regurgitation, or acute right-sided heart failure may precipitate this syndrome. Device closure of the PFO may improve symptoms and oxygen saturation.

Atrial septal aneurysm is characterized by mobile, redundant atrial septal tissue that is often associated with a PFO. Atrial septal aneurysm with a PFO reportedly increases the risk for stroke compared with a PFO alone. Results of a randomized, open-label trial demonstrated that patients presenting with cryptogenic stroke in the setting of an atrial septal aneurysm with PFO had a lower rate of stroke recurrence when treated with PFO closure combined with antiplatelet therapy than with antiplatelet therapy alone. Rarely, surgical excision and defect closure is considered based on anatomic features.

Atrial Septal Defect

Pathophysiology and Genetics

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a flaw or hole in the atrial septum resulting in a left-to-right shunt with eventual right-sided cardiac chamber dilatation in most patients.

ASDs are generally classified by their location (Figure 36). Ostium secundum defects, the most common type of ASDs (75% of cases), are located in the mid portion of the atrial septum and are usually isolated anomalies. Located in the lowest portion of the atrial septum, ostium primum defects (15%–20% of ASDs) are a component of endocardial cushion defects. Associated abnormalities include mitral valve, ventricular septum, and subaortic anomalies. Sinus venosus defects (5%–10% of ASDs) are located near the superior vena cava or, rarely, the inferior vena cava; anomalous pulmonary venous connection (typically involving the right upper pulmonary vein) is present in more than 90% of patients with this defect. A coronary sinus ASD (<1% of cases) is a communication between the left atrium and the coronary sinus. These defects are commonly associated with a persistent left-sided superior vena cava or complex congenital heart lesions.

ASDs are rarely associated with genetic syndromes. The Holt-Oram syndrome involves bilateral upper extremity abnormalities and congenital heart defects, commonly an ASD. Familial ostium secundum ASDs may be autosomal dominant or linked to chromosome 5. Congenital heart defects are relatively common in patients with Down syndrome; the most frequent abnormalities reported are atrioventricular septal defects, including ostium primum ASD.

Clinical Presentation

ASDs may be suspected in patients with unexplained right heart enlargement or atrial arrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation is a common finding in adults with an ASD. The atrial fibrillation risk decreases but does not normalize after ASD closure. ASD size and associated defects influence the age of presentation; symptoms include fatigue, exertional dyspnea, arrhythmias, and paradoxical embolism. Rarely, patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) are found to have isolated ASDs.

Clinical findings in patients with an ASD include a parasternal impulse, fixed splitting of the S2, and a pulmonary outflow murmur. A diastolic flow rumble across the tricuspid valve can occur with a large left-to-right shunt.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The electrocardiographic and radiographic findings in patients with an ASD are presented in Table 32.

TTE is the preferred imaging modality for identification of ostium secundum and primum ASDs. TTE also measures associated features, such as right-sided cardiac chamber enlargement, tricuspid regurgitation related to annular dilatation, and right ventricular pressure elevation. Agitated saline contrast injection (microcavitation study) in a peripheral vein during TTE may help identify an atrial-level shunt. Sinus venosus and coronary sinus ASDs are less readily diagnosed by TTE in adults and often require other imaging modalities, such as TEE, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging, or CT. CMR imaging and CT are rarely used as the primary imaging modality when an ASD is suspected but can identify anomalous pulmonary veins and quantify right ventricular volume and ejection fraction.

Cardiac catheterization is the only method for accurately calculating pulmonary-to-systemic blood flow ratio (Qp:Qs) but is rarely required for uncomplicated ASDs. Cardiac catheterization may be recommended in patients with an ASD and PH when ASD closure is being considered.

Treatment

The main indications for ASD closure include right-sided cardiac chamber enlargement or symptoms of dyspnea; closure is reasonable for orthodeoxia-platypnea syndrome and also before pacemaker placement because of the increased risk for systemic thromboembolism. In asymptomatic patients with a small ASD and no right heart enlargement, periodic clinical monitoring and echocardiographic imaging are recommended.

Percutaneous device closure is indicated for patients with an isolated ostium secundum ASD causing functional and hemodynamic consequences and is a reasonable option for asymptomatic patients with shunt-related hemodynamic consequences. Surgical ASD closure is indicated for nonsecundum ASDs, large secundum ASDs, unfavorable anatomy for device closure, and coexistent cardiovascular disease that requires operative intervention, such as coronary artery disease or tricuspid regurgitation.

Patients with an ASD and PH require specialty care; ASD closure may be considered for persistent left-to-right shunting without fixed PH. Medical therapy targeted at PH should also be considered.

Patients with an isolated anomalous pulmonary venous connection may present with clinical findings and TTE features similar to an ASD. Surgical redirection of the pulmonary vein is the only feasible treatment and requires surgical expertise in congenital heart disease.

Patients with small ASDs do not require physical activity limitation. Large left-to-right shunts result in self-limited exercise restriction. Patients with severe PH are advised to avoid isometric or competitive exercise.

Pregnancy is generally well tolerated in patients with an ASD in the absence of PH. The risk for congenital heart disease transmission with a sporadic ASD is estimated to be around 5%. Holt-Oram syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, and other genetic syndromes have variable inheritance; genetic counseling is suggested if a syndrome is suspected.

Follow-up After Atrial Septal Defect Closure

Follow-up is recommended for patients after surgical or percutaneous ASD closure. TTE and clinical assessment are recommended within the first year after closure and then periodically after that. Atrial fibrillation risk persists after closure, and frequency increases related to age at the time of ASD closure. Rare complications after device closure include device migration, erosion into the pericardium or aorta, and sudden death.

Ventricular Septal Defect

Pathophysiology

Ventricular septal defects (VSDs) are defined by their location on the ventricular septum (Figure 37). They are common at birth, but many small VSDs close spontaneously, resulting in lower prevalence by adulthood. Perimembranous VSDs are most common (80% of cases) and are usually isolated abnormalities. Muscular VSDs (10% of cases) can be located anywhere in the ventricular septum and often close spontaneously. Subpulmonary VSDs (also called outlet or supracristal VSDs) account for approximately 6% of defects in non-Asian persons and 33% in Asian persons and are associated with aortic regurgitation caused by aortic cusp distortion. Inlet VSDs (4% of cases) occur in the superior-posterior portion of the ventricular septum adjacent to the tricuspid valve. They occur as part of the atrioventricular septal defect complex, characteristically seen in patients with Down syndrome.

Clinical Presentation

The presentation of an isolated VSD depends on the VSD size and pulmonary vascular resistance. A small VSD without PH presents with a loud (often palpable) holosystolic murmur located at the left sternal border that may obliterate the S2. Small VSDs do not cause left heart enlargement or PH.

A VSD with a moderate left-to-right shunt may cause left ventricular volume overload and PH. Patients are asymptomatic for many years but eventually present with heart failure symptoms. A displaced left ventricular apical impulse suggests volume overload. A holosystolic murmur at the left sternal border is noted; the pressure gradient between the ventricles determines the murmur quality and duration. Progressive PH results in shortening of the murmur.

VSDs associated with large left-to-right shunts are usually detected by the presence of a murmur, heart failure, and failure to thrive in infancy. Failure to close the defect early in life usually causes fixed PH within several years with subsequent development of Eisenmenger syndrome (see Eisenmenger Syndrome) and shunt reversal.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The electrocardiographic and radiographic findings in patients with a VSD are presented in Table 32.

TTE is the imaging modality of choice for identification of VSD location, size, and hemodynamic impact. Rarely, TEE, CMR imaging, or CT is needed to delineate cardiac anatomy when TTE is unsatisfactory. Cardiac catheterization is primarily performed to delineate the Qp:Qs ratio and pulmonary pressures.

Treatment

VSD closure is indicated when the Qp:Qs ratio is 2.0 or greater with evidence of left ventricular volume overload or a history of endocarditis. Most patients are treated surgically, but percutaneous device closure is an option for select VSDs.

VSD closure is not indicated for patients with a small left-to-right shunt and no chamber enlargement or valve disease, but periodic clinical evaluation and imaging are recommended. Large VSDs with shunt reversal (right-to-left shunting) and PH (Eisenmenger syndrome) should not be closed because this causes clinical deterioration owing to reduced cardiac output.

Patients with small VSDs do not require activity restrictions. If the pulmonary artery pressure is greater than 50% of systolic blood pressure, isometric or competitive exercise is discouraged.

Pregnancy in women with VSDs is generally well tolerated in the absence of PH; women with VSDs and associated fixed PH should be counseled to avoid pregnancy.

Follow-up After Ventricular Septal Defect Closure

Residual or recurrent VSD, arrhythmias, PH, endocarditis, and valve regurgitation are recognized complications following VSD closure. Clinical assessment and TTE are recommended within 1 year of VSD closure. Subsequent follow-up frequency depends on clinical and cardiac status.

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Pathophysiology

A patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a persistent fetal connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery. Prematurity and maternal rubella predispose to a PDA. It may be an isolated abnormality or associated with other congenital cardiac defects.

Clinical Presentation

The typical murmur of a PDA is a continuous “machinery” murmur that envelops the S2, making it inaudible; the murmur is heard beneath the left clavicle. A tiny PDA is generally asymptomatic and inaudible. Patients with a moderate-sized PDA may present with bounding pulses, a wide pulse pressure, left-heart enlargement and dysfunction, and, rarely, clinical heart failure.

A large unrepaired PDA may cause PH with eventual shunt reversal (Eisenmenger syndrome); characteristic features of an Eisenmenger PDA are clubbing and oxygen desaturation affecting the feet but not the hands, owing to desaturated blood reaching the lower extremities preferentially (differential cyanosis).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The electrocardiographic and radiographic findings in patients with a PDA are presented in Table 32.

TTE is the imaging modality of choice for identification of a PDA. The PDA may be difficult to visualize in patients with severe PH owing to equalization of pressures between the aorta and pulmonary artery. In patients with a PDA and PH, cardiac catheterization is used to determine shunt size and reversibility of PH. Angiography confirms PDA morphology and helps determine whether percutaneous closure is feasible. TEE, CT, and CMR imaging may identify a PDA but are not the primary diagnostic techniques.

Treatment

PDA closure is indicated for left-sided cardiac chamber enlargement in the absence of severe PH. Percutaneous or surgical closure may be performed; referral to a congenital cardiac center for consideration of closure options is recommended.

A tiny PDA requires no intervention. PDA closure is reasonable for small PDAs with previous endocarditis. Moderate-sized PDAs are generally closed percutaneously. Large PDAs with severe PH and shunt reversal should be observed; closure may be detrimental, but medical therapy for PH should be considered.

Patients with a small PDA without PH do not require physical activity restrictions, and women should be able to tolerate pregnancy.

Pulmonary Valve Stenosis

Pathophysiology

Pulmonary valve stenosis (PS), an autosomal dominant disorder, causes obstruction to right ventricular outflow and is usually an isolated valve lesion. Isolated PS is associated with Noonan syndrome, which includes short stature, variable intellectual capacity, neck webbing, and ocular hypertelorism (abnormally increased distance between the orbits).

Clinical Presentation

Mild and moderate PS is generally asymptomatic. On physical examination, mild PS is characterized by a normal jugular venous waveform and precordial impulse.

Severe PS can cause exertional dyspnea. Right ventricular hypertrophy caused by pressure overload results in a prominent a wave on the jugular venous pressure waveform and a palpable right ventricular lift.

Auscultatory findings in PS include a systolic ejection click immediately after the S1 (which is the only right-sided heart sound to decrease during inspiration), followed by a crescendo-decrescendo murmur. In severe PS, the ejection systolic murmur at the left sternal border increases in intensity and duration, and the pulmonary valve component of S2 is delayed (splitting of S2) and eventually disappears. A right ventricular S4 is often heard in severe PS.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The electrocardiographic and radiographic findings in patients with PS are presented in Table 32.

TTE is the imaging modality of choice for identification of PS. Severe PS is present when the peak gradient is 50 mm Hg or greater. Treatment options depend on valve mobility, calcification, and the effects of obstruction on the right ventricle. PS causes right ventricular hypertrophy. Right ventricular dilatation should prompt a search for an associated lesion, such as pulmonary valve regurgitation or an ASD. TEE, CMR imaging, and CT are not routinely used in patients with PS. Cardiac catheterization is performed when percutaneous intervention for PS is considered.

Treatment

Pulmonary balloon valvuloplasty is the preferred treatment for valvular PS. It is indicated for asymptomatic patients with appropriate pulmonary valve morphology who have a peak Doppler gradient of at least 60 mm Hg or a mean gradient greater than 40 mm Hg and pulmonary valve regurgitation that is less than moderate. Balloon valvuloplasty is also recommended for symptomatic patients with appropriate valve morphology who have a peak Doppler gradient of greater than 50 mm Hg or a mean gradient greater than 30 mm Hg. Surgical intervention is recommended for PS associated with a small annulus, more than moderate pulmonary valve regurgitation, severe subvalvar or supravalvar PS, or another cardiac lesion that requires operative intervention.

Patients with mild and moderate PS (peak gradient <50 mm Hg) do not require exercise restriction. Patients with severe PS should participate only in low-intensity sports.

Pregnancy is generally well tolerated with PS; percutaneous valvotomy has been performed during pregnancy for severe symptomatic PS. Sporadic congenital heart disease recurrence in offspring is rare. Noonan syndrome should be suspected with PS recurrence in offspring.

Follow-up After Pulmonary Valve Stenosis Repair

Patients with previous PS intervention (balloon or surgical) often have severe pulmonary valve regurgitation; thus, long-term clinical and TTE follow-up is recommended. The frequency of follow-up depends on regurgitation severity and impact on the heart.

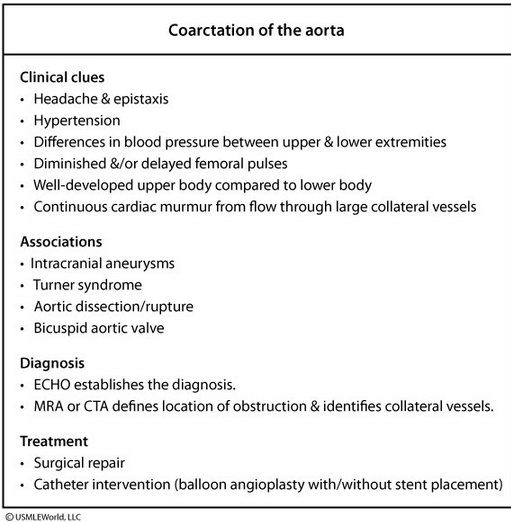

Aortic Coarctation

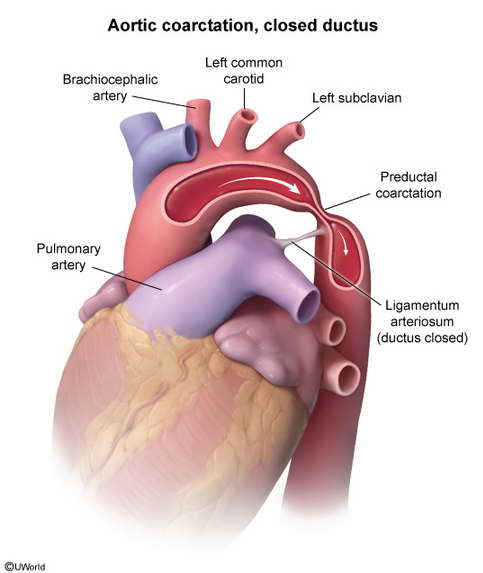

Pathophysiology

Aortic coarctation is a discrete narrowing of the aorta, usually located just beyond the left subclavian artery, causing hypertension proximal and hypotension distal to the narrowing.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with aortic coarctation may present with heart failure early in life. Adults are usually asymptomatic, but exertional leg fatigue or headaches may occur. Upper extremity hypertension and reduced blood pressure and pulse amplitude in the lower extremities cause a radial artery–to–femoral artery pulse delay. A systolic or continuous murmur is heard in the left infraclavicular region or over the back. A murmur from collateral intercostal vessels may also be audible and palpable over the chest wall. Fifty percent of patients with aortic coarctation have a bicuspid aortic valve. Auscultation of the heart may reveal an ejection click, a systolic murmur at the cardiac base, or, sometimes, an S4.

Turner syndrome, a chromosomal abnormality secondary to partial or total loss of chromosome X, is often associated with congenital cardiac disease, including coarctation. Turner syndrome is characterized by short stature, webbed neck, broad chest, and widely spaced nipples. Aortic coarctation is also associated with aortic and subaortic stenosis, parachute mitral valve (Shone syndrome), ventricular septal defect, and cerebral aneurysms.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The electrocardiographic and radiographic findings in patients with aortic coarctation are presented in Table 32.

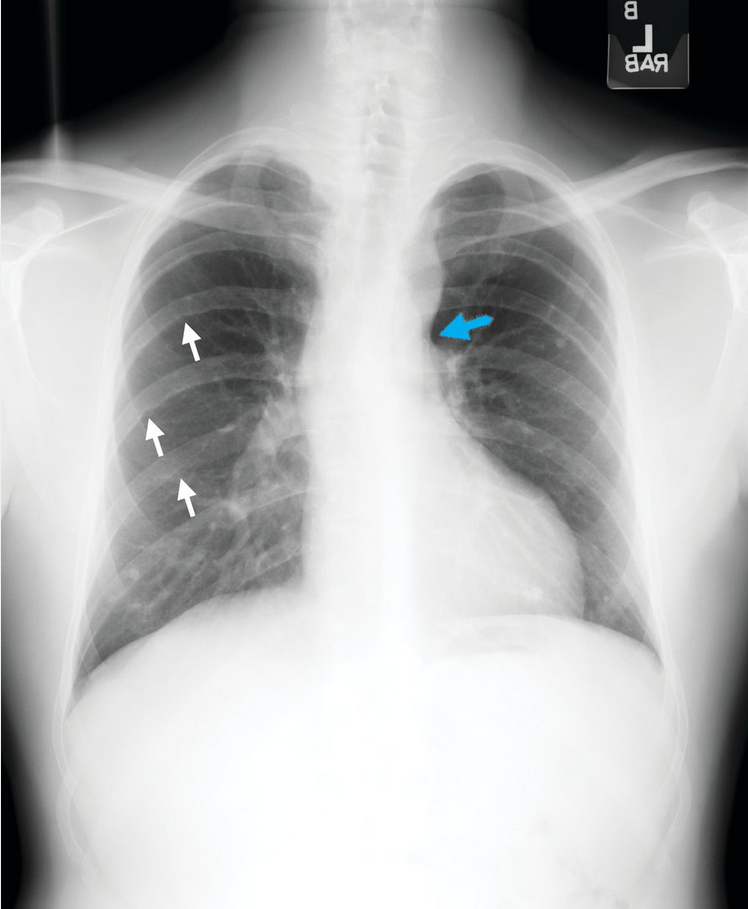

The characteristic radiographic features of aortic coarctation include the “figure 3 sign” (Figure 38), which is caused by dilatation of the aorta above and below the area of coarctation. Dilatation of intercostal collateral arteries as a result of aortic obstruction may lead to the radiographic appearance of rib notching.

TTE is often the initial diagnostic test in patients suspected of having aortic coarctation; it usually identifies the coarctation and associated features, such as bicuspid aortic valve and left ventricular hypertrophy. CMR imaging and CT are recommended to identify the anatomy, severity, and location of the coarctation; the presence of collateral vessels; and associated abnormalities, such as aortic aneurysm. Cardiac catheterization is primarily used in patients in whom percutaneous intervention is being considered.

Treatment

Severe aortic coarctation is associated with excess morbidity and mortality, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, aortic dissection, and heart failure. Age at the time of coarctation repair is the most important predictor of long-term survival.

Indications for intervention in patients with coarctation include a systolic peak (peak-to-peak) pressure gradient of 20 mm Hg or greater or radiologic evidence of severe coarctation with collateral flow. Percutaneous or surgical intervention options are available; selection depends on the length, location, and severity of coarctation and the presence of associated cardiovascular lesions.

Physical activity restriction is recommended for patients with severe postintervention residual or unrepaired coarctation, aortic stenosis, or a dilated aorta; these patients should avoid contact sports and isometric exercise.

A comprehensive preconception evaluation is warranted in all patients with coarctation who are considering pregnancy. Pregnancy is reasonable in women with repaired aortic coarctation without significant residua. Women with mild or moderate residua or unoperated coarctation will generally tolerate pregnancy well but should undergo blood pressure monitoring and cardiovascular evaluation during pregnancy. Pregnancy should be avoided by patients with severe unrepaired coarctation.

Follow-up After Aortic Coarctation Repair

Following coarctation repair, hypertension occurs in up to 75% of patients and should be treated. Additional intervention following repair may be required for bicuspid aortic valve, aortic aneurysm or dissection, recoarctation, coronary artery disease, systolic or diastolic heart failure, or intracranial aneurysm. Regular follow-up should include TTE, periodic aortic imaging, and evaluation by a cardiologist specializing in congenital heart disease.

Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is characterized by a large subaortic VSD, infundibular or valvular PS, aortic override, and right ventricular hypertrophy (Figure 39). It is the most common cyanotic congenital cardiac lesion. Repair is usually performed early in life; adults who have not undergone an operation are rarely encountered.

Genetic screening is recommended for all patients with TOF who are planning reproduction. Approximately 15% of patients with TOF have the 22q11.2 chromosome microdeletion (DiGeorge syndrome). When present, congenital heart disease inheritance is approximately 50%, compared with 5% in unaffected patients. TOF is common in persons with Down syndrome.

TOF repair involves VSD patch closure and relief of PS/right ventricular outflow tract obstruction by transannular patch placement; the transannular patch disrupts integrity of the pulmonary valve, causing severe pulmonary valve regurgitation. Severe long-standing pulmonary valve regurgitation causes right heart enlargement, tricuspid regurgitation, exercise limitation, and arrhythmias and is the most common reason for reoperation after TOF repair. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator should be considered in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and New York Heart Association functional class II or III symptoms. Annual congenital cardiology follow-up is recommended for patients with repaired TOF to determine optimal timing for intervention.

Diagnostic Evaluation after Repair of Tetralogy of Fallot

The electrocardiographic and radiographic findings in patients with repaired TOF are presented in Table 32.

Symptoms, arrhythmias, or right heart chamber enlargement should prompt a search for severe pulmonary valve regurgitation. Prolongation of the QRS complex reflects the degree of right ventricular dilatation; QRS duration of 180 milliseconds or longer and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia are risk factors for sudden cardiac death.

TTE is the imaging modality of choice for identifying valve dysfunction, residual VSD, left ventricular dysfunction, and aortic dilatation. CMR imaging or CT is preferred for assessment of right ventricular size and function, which helps determine appropriate timing for pulmonary valve replacement. Cardiac catheterization may be required to assess hemodynamics and residual shunts and to delineate coronary artery and pulmonary artery anatomy.

Treatment of Tetralogy of Fallot Residua

Indications for pulmonary valve replacement in patients with repaired TOF and severe pulmonary valve regurgitation include symptoms, decreased exercise tolerance, more than moderate right heart enlargement or dysfunction, arrhythmias, and development of tricuspid regurgitation. Tricuspid valve repair may also be needed. Pulmonary valve replacement is reasonable in asymptomatic patients with repaired TOF and ventricular enlargement or dysfunction and moderate or greater pulmonary regurgitation. Percutaneous pulmonary valve replacement is possible in select patients with previous TOF surgery.

Physical activity restriction is recommended for patients with repaired TOF and residual sequelae; contact sports and heavy isometric exercise should be avoided.

Adults with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease

General Management

Right-to-left cardiac shunts, such as palliated or unrepaired TOF and Eisenmenger syndrome, result in hypoxemia, erythrocytosis, and cyanosis. An increased erythrocyte mass is a compensatory response to improve oxygen transport.

Physical features include digital clubbing and central cyanosis. These patients are predisposed to arthropathy, scoliosis, gallstones, pulmonary hemorrhage or thrombus, paradoxical cerebral emboli or abscess, kidney dysfunction, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma, and hemostatic problems. Patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease should be evaluated annually by a congenital cardiac specialist.

Perioperative complications are common in patients with cyanosis, so elective procedures and operations should be performed at specialized multidisciplinary care centers; a congenital cardiac specialist should be consulted when patients are hospitalized. Additional considerations in these patients include antimicrobial prophylaxis for nonsterile procedures; placement of intravenous line filters to prevent paradoxical air embolism; and early ambulation, pneumatic compression devices, and anticoagulation to prevent venous stasis, venous thrombosis, and paradoxical embolism. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis is especially important in these patients because of the risk for paradoxical embolism if a venous thromboembolism were to occur.

Most patients with cyanosis have compensated, stable erythrocytosis. Phlebotomy is recommended for patients with symptomatic hyperviscosity (headaches and reduced concentration) with a hemoglobin level greater than 20 g/dL (200 g/L) and hematocrit greater than 65% in the absence of dehydration. Phlebotomy should be performed no more than three times each year and should be followed by fluid administration. Repeated phlebotomies deplete iron stores and cause iron-deficient erythrocytes or microcytosis, increasing the risk for stroke. Short-term iron therapy is administered for iron deficiency in patients with destabilized erythropoiesis.

Maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality increase related to the degree of cyanosis and pulmonary pressures; thus, pregnancy in patients with cyanosis is considered high risk.

Eisenmenger Syndrome

Eisenmenger syndrome is severe PH with cardiac shunt reversal (right-to-left shunting) caused by a long-standing, unrepaired VSD, PDA, or ASD. TTE evaluation and appropriate intervention has decreased the frequency of Eisenmenger syndrome, but PH related to complex congenital heart disease is increasingly identified.

Conservative medical measures for patients with Eisenmenger syndrome include avoiding iron deficiency, dehydration, acute exposure to excess heat, and moderate or severe strenuous or isometric exercise. Phlebotomy is rarely performed. Additionally, long-term altitude exposure should be avoided or limited because it results in a reduced partial pressure of oxygen. Air travel should be undertaken in pressurized aircrafts; supplemental oxygen may be beneficial with prolonged air travel.

All patients with Eisenmenger syndrome should undergo annual evaluation by a congenital cardiac specialist. Noncardiac surgery should be performed at centers with expertise in the care of patients with complex congenital cardiac disease. Patients with progressive cardiovascular symptoms may benefit from pulmonary vasodilator therapy or, in rare cases, heart and lung transplantation.

Women with Eisenmenger syndrome should be cautioned to avoid pregnancy because of the high risk for maternal mortality.