carbon monoxide poisoning

- related: Occupational Lung Disease, toxicology and toxic ingestions

- tags: #literature #pulmonology #icu

Cause

CO is a tasteless, odorless, and colorless gas that may cause a headache, weakness, dizziness, and nausea, along with tachycardia and tachypnea. Toxicity occurs owing to its effect on oxygen binding to the hemoglobin molecule; the gas binds to hemoglobin, forming COHb, with a much greater affinity to hemoglobin than oxygen. This reduces the oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin and leads to cellular hypoxia. COHb increases the affinity of unbound hemoglobin for oxygen, thus causing a leftward shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve. Additionally, CO binds to the heme moiety of the cytochrome C oxidase in the electron transport chain and inhibits mitochondrial respiration. These effects cause a lower tissue and intracellular PO2 than would otherwise be expected for a given blood oxygen concentration. The hemoglobin concentration and the PO2 of blood may be normal, but the oxygen content of the blood is reduced significantly.

Carbon monoxide, a colorless and odorless gas, can be potentially fatal after exposure if not properly diagnosed and treated. Carbon monoxide poisoning is associated with:

- Automobile exhaust

- Inadequately ventilated heaters (hence most commonly occurring in the winter)

- Methylene chloride ingestion (converts to CO hepatically)

Although it has no detectable odor, CO used in industrial processes is often mixed with other gases, such as ethyl mercaptan, that do have an odor for safety purposes. CO is a common industrial hazard resulting from the incomplete combustion of natural gas or any other carbonaceous material such as gasoline, kerosene, oil, propane, coal, or wood.

Pathophysiology

Carbon monoxide has several pathophysiological consequences on oxygen transport and utilization:

- Carbon monoxide binds to heme with 240x the affinity of oxygen forming carboxyhemoglobinemia

- Allosteric changes of the heme moiety prevent oxygen unloading peripherally

- CO binds to various proteins affecting oxidative phosphorylation

Symptoms

In addition to a history consistent with CO exposure, patients with mild CO poisoning present with:

- Headache (most common symptom)

- Viral-like symptoms (e.g. dizziness, nausea, vomiting, malaise)

- Altered mental status

Patients severely exposed to carbon monoxide typically present with:

- Neuropsych symptoms: seizures, delirium

- Cardiology symptoms: myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias

- **Mortality **

Physical exam signs of carbon monoxide toxicity may include:

- Tachycardia

- Pallor or Cherry-red skin

- Memory disturbance

- Neuropsychiatric: emotional lability, impaired judgment

- Pulmonary edema

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of carbon monoxide poisoning is dependent upon:

- History

- Physical exam

- Arterial blood gases demonstrating elevated carboxyhemoglobin levels

Following the diagnosis of carbon monoxide poisoning, an electrocardiogram is recommended to detect for ischemia as myocardial infarction is a common complication.

Carboxyhemoglobin shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the left, impairing the ability of heme to unload oxygen at the tissue level. This results in tissue hypoxia. The kidney responds to tissue hypoxia by producing more erythropoietin (EPO). EPO stimulates the bone marrow to differentiate more red blood cells. Chronic CO toxicity is a cause of secondary polycythemia.

Chronic tobacco smokers may have up to 15% carboxyhemoglobin at baseline.

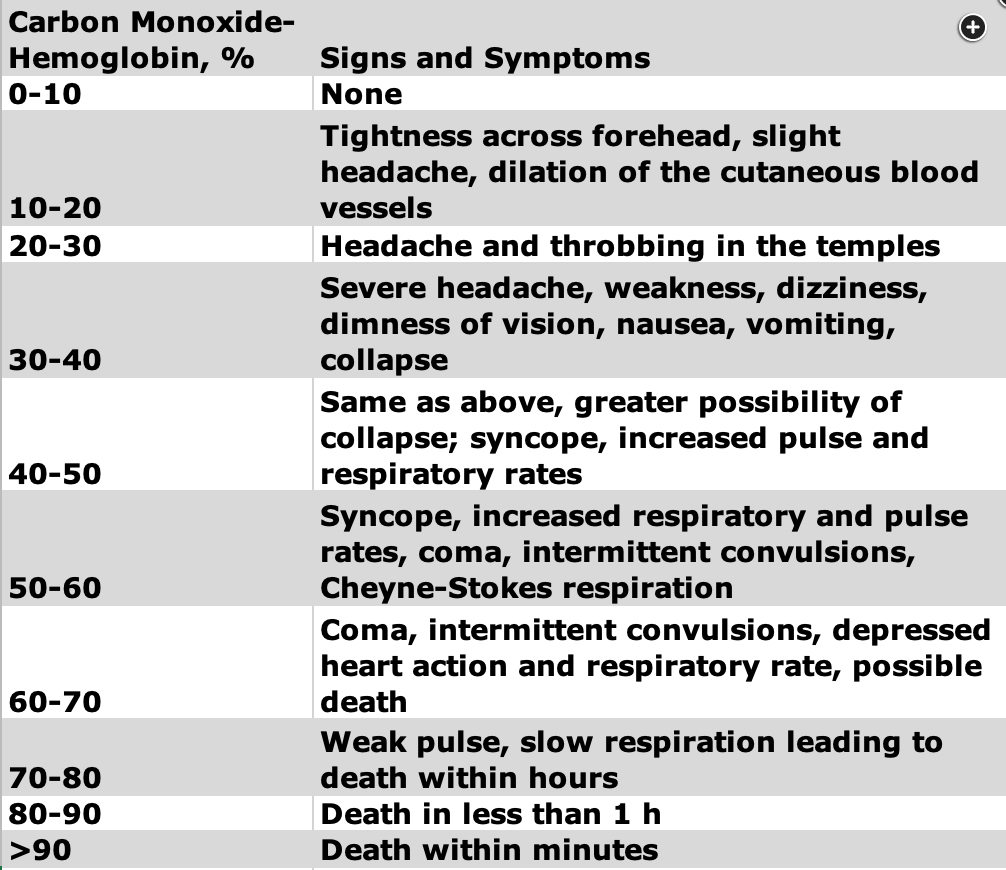

Carbon monoxide saturation levels above 40% is considered to be severe exposure, whereas levels above 55% can potentially be fatal.

Management

The management of carbon monoxide poisoning includes:

- Removal from the carbon monoxide source

- 100% high-flow oxygen or a hyperbaric oxygen chamber (decreases the half life of CO)

- Intubate if necessary

This patient has carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning as evidenced by headache, nausea, and dizziness in the context of a risk factor for CO exposure (power outage) and elevated carboxyhemoglobin level. Clinical manifestations of CO poisoning are nonspecific and can range from dyspnea, dizziness, and headaches to arrhythmia, cardiovascular collapse, and severe neurologic impairment. CO exposures are most commonly due to fires, burns, engine exhaust, defective furnaces or heating systems, and motor vehicles running in areas without adequate ventilation. A report in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated a significant increase in emergency department visits for CO poisoning in the days before and after power outages, likely because individuals were using energy sources that emit CO in poorly ventilated areas.

CO is a colorless, odorless gas that binds to hemoglobin with an affinity that is approximately 240 times that of oxygen. As a result, very low levels of CO can result in the development of carboxyhemoglobin. Carboxyhemoglobin impairs oxygen delivery to tissues and, importantly, binds to the cytochrome C oxidase site of mitochondria, which is the primary site of oxygen consumption. This in turn impairs aerobic metabolism and decreases adenosine triphosphate production, which leads to cellular dysfunction and is ultimately fatal.

Because binding of CO to the oxygen-carrying heme sites on hemoglobin is competitive and partially reversible, treatment with oxygen allows oxygen to displace CO and generate more oxyhemoglobin in the RBC. This results in significant reduction of the carboxyhemoglobin half-life. Therefore, oxygen therapy is an essential part of treatment for CO poisoning. The decision between delivering normobaric oxygen or hyperbaric oxygen depends on the severity of illness and the logistics of transferring a patient who is critically ill to a center with hyperbaric oxygen capabilities. Hyperbaric oxygen is recommended if the individual is unconscious, has persistent altered mental status, has severe acidosis with pH less than 7.25, has carboxyhemoglobin level above 25%, or has evidence of end-organ ischemia. Some evidence suggests that hyperbaric oxygen therapy decreases the incidence of delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms in individuals with CO poisoning. Multiple studies have attempted to compare the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen and normobaric oxygen in the treatment of CO poisoning. However, many of these studies have threats to internal validity that limit our ability to draw accurate conclusions from the results. While hyperbaric oxygen should be considered in all cases of CO poisoning, the first step in treatment is use of normobaric oxygen, which is readily available, while awaiting the decision to initiate hyperbaric oxygen.

Note that many pulse oximeters are unreliable in suspected CO poisoning, because the wavelength cannot distinguish between oxyhemoglobin and carboxyhemoglobin. In addition, the CO concentration required to cause poisoning is low enough that it may not affect the partial pressure of dissolved oxygen in blood.

Sodium bicarbonate is the treatment for tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) toxicity in patients with hypotension, cardiac arrhythmia, or widened QRS interval. Although this patient takes amitriptyline, the ECG in Figure 1 shows a normal QRS interval. Individuals with TCA toxicity have a broad range of clinical signs and symptoms that vary based on time of presentation and amount of medication ingested. Because of the antihistamine properties of TCAs, individuals with toxicity may have drowsiness, confusion, delirium, and hallucinations. Anticholinergic effects of the drug may lead to flushing, mydriasis, urinary retention, and hyperthermia. Sinus tachycardia and refractory hypotension are also common owing to α1-adrenergic receptor antagonism.

Methylene blue is a treatment for methemoglobinemia. Acquired methemoglobinemia can be due to ingestion of culprit drugs such as antimalarial agents, dapsone, and sulfonamides. Symptoms of methemoglobinemia are nonspecific and include weakness, dizziness, headaches, metabolic acidosis, and severe neurologic disease. Individuals become symptomatic at methemoglobin levels >10% to 20%, measured by co-oximetry.123456

A 35-year-old man with no previous history is brought to the ED by emergency medical services after a fire. The furnace at his apartment was not working while outside temperatures were -17.8°C. He used a space heater to stay warm, which eventually caught fire.

On arrival to the ED, he has soot on his face. His nose hairs are intact, and there are no burns to his face, neck, or body. His voice is slightly muffled when he tries to speak, and he tells you he feels nauseated and has a slight headache. His pulse oximetry is 95% breathing room air.

After definitive airway management, what is the best next step?

- ABG with co ox

Links to this note

-

fire and smoke inhalation exposures

- related: carbon monoxide poisoning, Pulmonary Diseases

-

seizure can be result of hyperbaric oxygen therapy

- related: carbon monoxide poisoning

-

differentiating between cyanide and carbon monoxide toxicity

- related: cyanide toxicity, carbon monoxide poisoning

Footnotes

-

Rose JJ, Wang L, Xu Q, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning: pathogenesis, management, and future directions of therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(5):596-606. PubMed ↩

-

Thom SR, Taber RL, Mendiguren II, et al. Delayed neuropsychologic sequelae after carbon monoxide poisoning: prevention by treatment with hyperbaric oxygen. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(4):474-480. PubMed ↩

-

Weaver LK, Hopkins RO, Chan KJ, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(14):1057-1067. PubMed ↩

-

Weaver LK. Clinical practice: carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1217-1225. PubMed ↩

-

Worsham CM, Woo J, Kearney MJ, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning during major U.S. power outages. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(2):191-192. PubMed ↩