Dermatologic Emergencies

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Retiform Purpura

Retiform is a descriptive term for a net-like, branching, or stellate configuration, reflecting the vascular structure of the skin. Purpura refers to the nonblanching dark red or purple color resulting from extravasation of erythrocytes into the skin (Figure 127). Retiform purpura signifies total occlusion of cutaneous arterioles with downstream necrosis and hemorrhage in the watershed area of the vessel. Occlusion of several adjacent vessels may result in purpura and necrosis of body segments (Figure 128), particularly in acral regions (digits, ears, genitals).

Retiform purpura is a description, not a diagnosis, and the cause must be determined to preserve life and limb. Because of their devastating consequences, thrombotic and embolic causes should be considered first. Thrombotic causes can be due to unregulated coagulation such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, or warfarinor heparin-induced thrombosis. The heart and large vessels may be sources of emboli as seen with bacterial or marantic endocarditis, atrial myxoma, or cholesterol emboli following an intravascular procedure.

Diagnosis is made by history and examination (Table 26). The evaluation should be directed by the most likely associated disorder. A wide net of testing may be necessary in the critically ill patient without a clearly identified underlying condition. In a stable patient, skin biopsy can further direct the evaluation. Treatment is directed toward the underlying cause.

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) minor is an immune-mediated condition that can be recognized by its classic targetoid plaques with characteristic histopathologic features. The sharply defined circinate plaques feature two differently colored concentric rings (pale inner ring, red outer ring) surrounding a pale, dusky, vesiculated or crusted center (Figure 129). These plaques typically appear on the face and acral sites, such as the back of the hands, the arms, legs, or feet. The palms and soles may also be involved. Crops of lesions persist for approximately 7 days and resolve without scarring. Most cases of EM minor are caused by infections, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 being the most common followed by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, particularly in children. Drug-induced cases of EM minor are less frequent and typically result from NSAIDs, antiepileptic agents, or sulfonamides. Mucosal involvement is rare, but if present, is trivial.

Targetoid lesions of erythema multiforme characterized by two concentric rings (pale inner ring, red outer ring) surrounding a pale or dusky center.

EM major has severe mucosal involvement and systemic symptoms in addition to typical skin findings found in EM minor. Lesions in the mouth blister and become painful erosions. They are often polycyclic and involve the buccal mucosa and lips, where the edges may suggest the concentric rings of EM. The eyes, nasopharynx, and genitals are less commonly affected. Fever and malaise may precede rash, and joint pain and swelling have been described. Internal organ involvement should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis. Skin biopsy can be helpful when the diagnosis is unclear, and direct immunofluorescence can be used to exclude the possibility of autoimmune blistering disease. EM can recur, and in approximately 70% of patients this is associated with herpes simplex virus infection. These patients may benefit from suppressive antiviral therapy. Antimicrobial therapy is helpful if M. pneumoniae is the trigger of EM. If a drug is implicated, the immediate first step is stopping the drug. Systemic glucocorticoids are highly effective for decreasing inflammation and pain, even when patients have an infectious trigger, and short courses (3-4 weeks) should be considered early in the disease.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) refers to the rapid onset of a pustular rash following a medication exposure in a patient without a history of pustular psoriasis. Onset may be as soon as 1 day after exposure to the medication or a few days at most. Patients present with fever, erythema, and eventually develop myriad dense non-folliculocentric pustules, primarily in skin folds and on the trunk (Figure 132). A total of 80% of cases are caused by antibiotics. Most cases are self-limited and resolve within 2 weeks. Treatment consists of cessation of the causative agent and supportive care, but topical and systemic glucocorticoids may be helpful for symptomatic relief. The condition carries a mortality rate of less than 5%.

Erythroderma

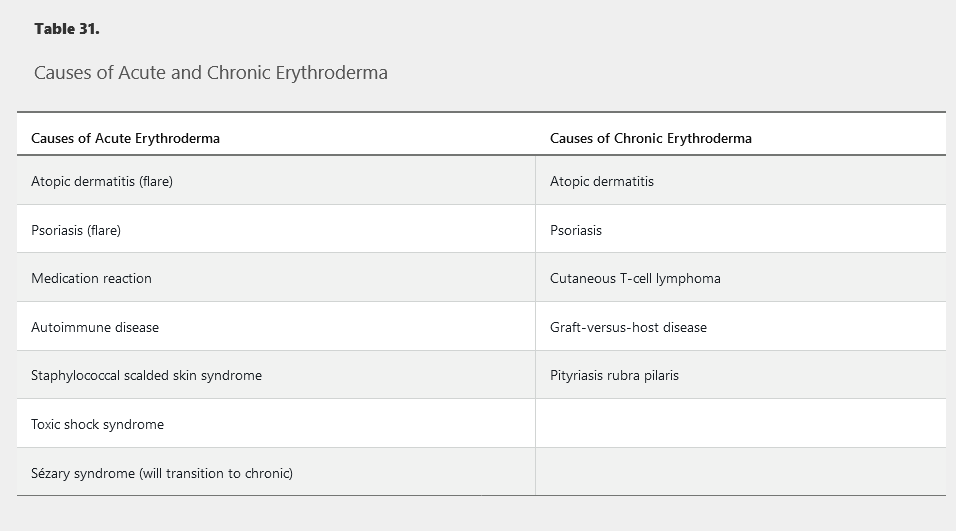

Erythroderma is defined as diffuse erythema covering 80% to 90% body surface area and is commonly associated with pruritus, peripheral edema, erosions, scaling, and lymphadenopathy (Figure 133). The most common causes are idiopathic (up to 40%), exacerbation of a preexisting rash, or medication reaction (Table 31). Atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare to erythroderma following injudicious usage and abrupt cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. Alopecia, nail dystrophy, and thickening of the palms and soles are indicative of a long-standing cause such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, graft-versus-host disease, psoriasis, or pityriasis rubra pilaris. Drug reactions, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and autoimmune bullous diseases often have a more acute onset without a long-standing history of preceding dermatosis. When erythroderma is acute, thick scaling of the palms and soles or nail changes do not occur. Complications may result from heat and fluid loss across the inflamed skin.

Psoriasis vulgaris can flare to erythroderma following use of systemic glucocorticoids. The most common cause of erythroderma, or redness over 80% body surface area, is a preexisting condition. Peripheral edema, erosions from excoriations due to severe pruritus, and scaling are common findings. Owing to compromise of the skin barrier, affected patients are at risk for dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, protein loss, heat loss, and infection, which can be fatal. Short courses of systemic glucocorticoids in a patient with psoriasis can result in a striking increase in skin disease upon abrupt cessation. The presence of lamellar scale that bleeds when peeled away (Auspitz sign) and nail pitting support the diagnosis of erythrodermic psoriasis.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) can also present with erythroderma. This represents a delayed response to a medication several weeks after initiation. Patients present with rash, striking facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia (or less common atypical lymphocytosis), lymphadenopathy, and evidence of organ involvement such as acute kidney injury or abnormal liver chemistry tests.

Management of erythroderma involves treatment of infection and managing fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Emollients will help to restore the skin barrier, and topical glucocorticoids and systemic antihistamines will improve pruritus.

Erythroderma with redness and scaling secondary to pityriasis rubra pilaris.