Peripheral Artery Disease

- related: Cardiology

- tags: #cardiology

- Asymptomatic (20%-50%)

- Physical examination findings

- ↓ or absent pulses below the level of stenosis

- Occasional bruits over stenotic lesions

- Poor wound healing in areas of diminished perfusion

- Cool extremity with prolonged venous filling time

- Shiny, atrophied skin with nail changes

- Foot pallor with leg elevation (Buerger test)

- Specific pain patterns

- Buttock & hip pain (aortoiliac disease)

- Bilateral diminished or absent groin pulses, occasional bruits over iliac & femoral arteries, muscle atrophy & slow wound healing in legs

- Leriche syndrome: Triad of erectile dysfunction, buttock & hip pain, absent femoral pulses on examination

- Thigh pain (aortoiliac or common femoral disease): Normal groin pulses but decreased distal pulses

- Calf pain (most common): Increasing pain with exertion & decreased with rest

- Upper 2/3 of calf (superficial femoral artery disease)

- Lower 1/3 of calf (popliteal artery disease)

- Foot pain (tibial or peroneal artery disease) This patient’s pain with walking uphill and relief with rest suggest intermittent claudication due to occlusive peripheral artery disease (PAD) (Table). Localized hip or buttock area pain suggests aortoiliac occlusive disease. Patients typically present with aching pain and thigh or hip weakness while walking. Leriche’s syndrome is a triad of claudication, diminished femoral pulses, and erectile dysfunction due to severe aortoiliac occlusive PAD.

- Buttock & hip pain (aortoiliac disease)

This patient’s atherosclerotic risk factors of diabetes and hyperlipidemia place him at high risk for PAD. Physical examination in PAD patients may show diminished or absent femoral pulses, bruits over femoral or iliac arteries, cool extremities, prolonged venous filling time, skin or muscle atrophy, prolonged wound healing, and foot pallor with elevation of the affected leg (Buerger’s test).

Lumbar spondylosis or degenerative arthritis of the lumbosacral spine can lead to decreased lumbar spine mobility due to disc bulging or spinal stenosis compressing the nerve roots. Patients may present with neurogenic claudication or pseudoclaudication (worsening pain with standing or erect posture, but relieved with sitting or lying down), focal weakness, or sensory loss in the distribution of 1 or more spinal nerve roots.

Epidemiology and Screening

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is most commonly characterized by narrowing of the aortic bifurcation and arteries of the lower extremities, including the iliac, femoral, popliteal, and tibial arteries. Stenosis in the upper extremity arteries, typically at the origin of the subclavian arteries or at branch points of other major vessels, can also occur. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause. Risk factors for PAD include smoking (current or past), diabetes mellitus, and increasing age. PAD occurs at a later age in women than in men, and because women have a longer lifespan, the overall prevalence of PAD is higher in women. The incidence of PAD begins to increase around age 40 years and rises to approximately 10% at age 70 years.

PAD is considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent, and both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with PAD are at increased risk for ischemic events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death. Patients with atherosclerotic risk factors (smoking, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, advanced age) who have atypical limb symptoms (leg weakness, paresthesias), exertional leg discomfort, and/or nonhealing ulcers should undergo initial testing with ankle-brachial index (ABI) measurement. According to guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, a screening ABI is reasonable in asymptomatic persons with one of the following characteristics that signify increased risk: (1) age 65 years and older, (2) age 50 to 64 years with risk factors for atherosclerosis or family history of PAD, (3) age younger than 50 years with diabetes and one additional risk factor for atherosclerosis, or (4) known atherosclerotic disease in another vascular bed (coronary, carotid, subclavian, renal, or mesenteric artery stenosis, or abdominal aortic aneurysm). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support screening for lower extremity PAD with an ABI in all patients, especially those without risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Measurement of bilateral arm pressures is indicated in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with atherosclerotic risk factors to assess for upper extremity PAD.

Clinical Presentation

Because lower extremity PAD is defined by an abnormal ABI value rather than by symptoms, there is a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Patients may present with exertional leg pain relieved by rest (intermittent claudication), atypical exertional leg pain, rest pain, nonhealing wounds, ischemic ulcers, or gangrene. Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with lower extremity PAD present with intermittent claudication, and less than 5% of patients present with critical limb ischemia. Most patients with upper extremity PAD have no symptoms, although patients may present with arm claudication, arm ischemia, or dizziness with arm activity (subclavian steal syndrome).

Patients with intermittent claudication often have reduced exercise capacity and functional status compared with ageand sex-matched controls. Their annual risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death is approximately 5% to 7%. Most patients with intermittent claudication have stable symptoms; however, symptoms worsen in approximately 25% of patients, and 10% to 20% of patients will undergo lower extremity revascularization procedures over a period of 5 years.

Critical limb ischemia, the most severe form of PAD, manifests as ischemic rest pain, tissue ulceration, and gangrene. Patients with critical limb ischemia often have reduced exercise capacity and functional status, and these patients have a 30% rate of major amputation and 20% mortality rate within 1 year of diagnosis.

Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

A detailed history, review of symptoms, and physical examination are critical in the evaluation of patients suspected of having vascular disease. Patients should be asked about walking impairment, atypical limb symptoms, intermittent claudication, and ischemic rest pain. In patients with exertional leg symptoms, intermittent claudication should be differentiated from pseudoclaudication (symptoms that arise from spinal stenosis) (Table 36). Patients should be questioned about skin breakdown and foot ulcers, and clinicians should educate patients on the importance of foot protection and wearing shoes (specifically, hard-soled shoes) when walking outside the home.

Elements of the physical examination of patients suspected of having PAD are listed in Table 37. Vascular examination of patients suspected of having lower extremity PAD should include comprehensive pulse examination, auscultation for bruits, and inspection of the feet for skin and toenail changes. Patients with PAD may exhibit diminished, absent, or asymmetric pulses, and bruits may be heard at or near sites of arterial stenosis. Patients with critical limb ischemia may have decreased temperature or lack of hair growth in the affected extremity, as well as evidence of poor wound healing or active ulceration (typically involving the digits, plantar aspect of the foot, or heel). Clinicians should distinguish between signs of chronic venous disease (leg edema; pigmented, brawny induration of the gaiter zone; ulceration of the shin or ankle) and critical limb ischemia when evaluating patients with leg ulcers because venous leg ulcers are treated differently than ulcerations in patients with critical limb ischemia (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology).

In patients with upper extremity PAD, a characteristic finding on physical examination is a difference in systolic blood pressures between the arms, typically more than 15 mm Hg.

“Venous claudication” is occasionally used to describe the lower-extremity discomfort in patients with chronic venous disease. These patients usually have associated findings of venous disease with leg swelling and varicosities, and the symptoms are worse with the limbs in a prolonged dependent position.

Diagnostic Testing

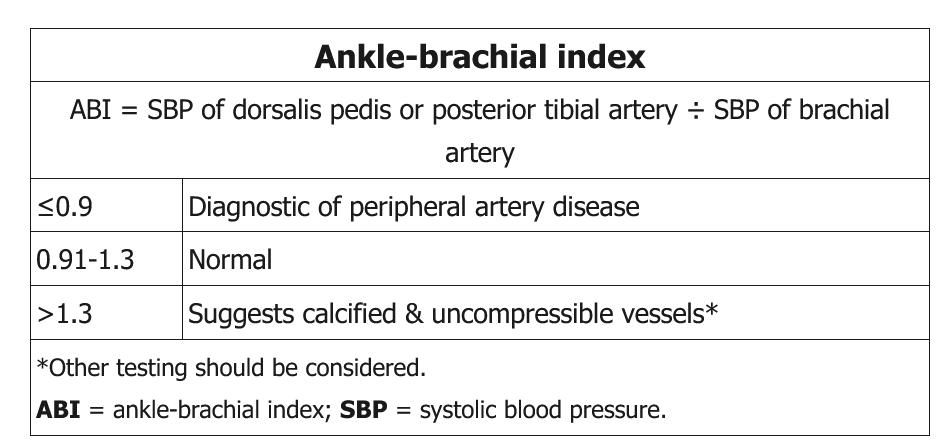

The most frequently used diagnostic modality to identify lower extremity PAD is measurement of the ABI, which is the ratio of lower extremity to upper extremity systolic blood pressures. ABI measurement is simple, inexpensive, and noninvasive, with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 90%. When undergoing ABI testing, patients should rest for 10 minutes in a supine position before the clinician measures the ankle pressures and brachial pressures with a Doppler machine. Blood pressures should be measured in both arms and in both legs at the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial ankle locations. To calculate the ABI for each leg, the higher ankle pressure in each leg is divided by the higher brachial artery pressure. In healthy persons, the ankle pressure should be the same as or slightly higher than the brachial pressure; therefore, a normal resting ABI is between 1.00 and 1.40 (Table 38). In the presence of atherosclerotic narrowing of the limb arteries, the downstream blood pressure and concomitant ABI value is lower. A resting ABI of 0.90 or less is diagnostic for PAD and correlates with abnormalities seen on imaging of the arterial tree. A resting ABI greater than 1.40 indicates the presence of noncompressible, calcified arteries in the lower extremities and is considered uninterpretable. In patients with an ABI greater than 1.40, a toe-brachial index is used for diagnosis. A toe-brachial index less than 0.70 is diagnostic for PAD.

Some patients with PAD and arterial calcification have non-compressible vessels, which can lead to falsely elevated ABI (>1.3). This is usually seen in the setting of diabetes mellitus and/or chronic renal failure. In such patients, further vascular studies, with measurement of toe-brachial index, pulse volume recordings, or arterial duplex ultrasound, should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis of PAD. The presence of high ABI >1.3 (similar to low ABI) is associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

An exercise ABI test is useful when resting ABI values are between 0.91 and 1.40 and the pretest probability of PAD is high. It requires ABI measurements at rest and after treadmill walking or plantar flexion exercises. The American Heart Association has proposed a postexercise ankle pressure decrease of more than 30 mm Hg or a postexercise ABI decrease of more than 20% as a diagnostic criterion for PAD. Other organizations have proposed a postexercise ABI of less than 0.90 and/or a 30–mm Hg drop in ankle pressure after exercise.

Segmental pressure measurements may be performed in a vascular laboratory to localize diseased vessels. This procedure involves pulse volume recordings (measurement of the magnitude and contour of blood pulse volume in the lower extremities) and blood pressure measurements at several locations in the lower extremities (high thigh, low thigh, calf, posterior tibial artery, and dorsalis pedis artery) (Figure 44).

Hemodynamic measurements (ABI, toe-brachial index, exercise ABI, and segmental pressure measurements) remain the most commonly used diagnostic tests for patients suspected of having lower extremity PAD. The ABI does not correlate with the patient’s perception of symptom severity or functional limitations; however, lower ABI values are associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death.

Other imaging tests used to delineate the anatomic location and severity of lower extremity PAD include arterial duplex ultrasonography, CT angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography (Table 39). These imaging modalities are most often used to plan for endovascular or surgical revascularization procedures. Invasive angiography is often preferred because endovascular revascularization procedures can be performed concurrently.

Duplex ultrasonography, CT angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography are also appropriate in patients with upper extremity PAD to confirm the diagnosis and plan for intervention, such as revascularization.

Medical Therapy

Treatment of PAD focuses on reducing cardiovascular risk; improving functional status, quality of life, and claudication symptoms; and preventing tissue loss and amputation.

Cardiovascular Risk Reduction

Cigarette smoking is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of PAD. Smoking cessation is associated with decreased risk for major amputation, improved patency rates following revascularization, and less disease progression. Smoking cessation is imperative to lower the risk for myocardial infarction and stroke and improve overall survival in patients with PAD.

Diabetes is also a strong risk factor for PAD; however, intensive glucose control has not been demonstrated to reduce macrovascular complications, including myocardial infarction, stroke, or amputation. Regardless, patients with PAD and diabetes should adhere to American Diabetes Association recommendations on diabetes management, with particular attention to foot care.

Dyslipidemia has a mild effect on the development of PAD. Patients with symptomatic PAD should be treated with high-intensity statin therapy, and patients with PAD who are older than 75 years or intolerant of high-intensity statins should be treated with moderate-intensity statin therapy (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine).

Hypertension also has a mild effect on the development of PAD, and control of blood pressure has been associated with reduction of cardiovascular events in patients with PAD. The 2017 high blood pressure guideline from the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and nine other organizations recommends a blood pressure target of less than 130/80 mm Hg in patients with PAD. There is no consensus on the antihypertensive therapy of choice in patients with PAD; therefore, thiazide diuretics, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers remain first-line agents in patients with PAD and hypertension. In patients at high risk for cardiovascular events or with comorbid conditions (such as diabetes), ACE inhibitors are effective in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Antithrombotic Therapy

Current guidelines recommend antiplatelet monotherapy in patients with PAD to reduce risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral arterial events. Despite little supporting evidence, aspirin has been recommended by experts as the primary antiplatelet agent in patients with PAD. In patients who are aspirin intolerant, clopidogrel is recommended as an acceptable alternative. There is no compelling evidence for the use of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin plus clopidogrel in patients with PAD alone. In the CHARISMA trial, patients with PAD who were treated with aspirin plus clopidogrel had a reduced rate of hospitalization for myocardial infarction and ischemic events, which was mitigated by a higher rate of bleeding.

Evidence from the TRA 2P–TIMI 50 trial demonstrated that vorapaxar, a thrombin receptor antagonist, was associated with improved limb endpoints (specifically, hospitalization for acute limb ischemia) when compared with placebo in patients with PAD. However, most patients in the TRA 2P–TIMI 50 trial were treated with aspirin, and 30% of patients were treated with aspirin plus clopidogrel. Vorapaxar was also associated with an increased risk for moderate or severe bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage.

In a large secondary prevention study of patients with prior myocardial infarction receiving aspirin therapy, ticagrelor was superior to placebo in reducing the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke and major adverse limb events in the subset of patients with PAD. Major bleeding was increased in patients randomly assigned to ticagrelor. However, the absolute risk for major bleeding in patients with PAD was lower than in patients without PAD.

There is no evidence that oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (such as warfarin) is more effective than antiplatelet monotherapy in patients with PAD, and anticoagulant therapy is associated with an increased risk for major bleeding. There is also no evidence that non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants are superior to antiplatelet agents in patients with PAD.

Symptom Relief

Improving functional status and improving quality of life are critical goals for patients with PAD. In patients who can exercise, supervised exercise training has been associated with improved functional performance and is recommended for patients with intermittent claudication. Systematic reviews comparing supervised exercise with home exercise have reported improvements in maximal walking distance and initial claudication distance that favor supervised exercise; however, no statistically significant differences in quality of life were observed. Despite its effectiveness and safety, supervised exercise training is limited by lack of insurance coverage and unavailability of these programs for patients with claudication.

Medical therapy for patients with intermittent claudication consists of cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with antiplatelet and vasodilator activity. Cilostazol has demonstrated increases in pain-free walking distance and overall walking distance in patients with claudication, and clinical guidelines recommend that patients with claudication be considered for a therapeutic trial of cilostazol. As with other oral phosphodiesterase inhibitors (for example, inotropes such as milrinone), the FDA has placed a black box warning on the use of cilostazol in patients with heart failure. There is no approved pharmacotherapy for patients with critical limb ischemia.

Interventional Therapy

Endovascular or surgical revascularization procedures are effective in improving symptoms, increasing functional capacity, and improving wound healing in patients with intermittent claudication or critical limb ischemia. Referral for revascularization is indicated in patients with lifestyle-limiting claudication, rest pain, ulceration, or gangrene, especially if there has been an inadequate response to exercise training, cilostazol, and/or wound treatment. Patients with critical limb ischemia (ABI <0.40, a flat waveform on pulse volume recording, and low or absent pedal flow on duplex ultrasonography) should be considered for urgent revascularization. Endovascular or surgical revascularization should also be considered in patients with a favorable risk-benefit ratio, which is determined by patient factors (age, frailty, comorbid conditions), anatomic factors (severity and burden of atherosclerotic disease, location of disease in lower extremities), operator expertise, and type of procedure. Revascularization is not recommended in asymptomatic patients.

Endovascular revascularization has dramatically increased in recent years because the procedure is minimally invasive and confers a lower risk for perioperative adverse events compared with surgical revascularization. Endovascular revascularization procedures include balloon angioplasty (standard, cutting, drug-coated), stenting (nitinol [nickel-titanium] bare metal and drug eluting), and atherectomy (laser, orbital, rotational, directional). In patients with isolated iliac disease, endovascular revascularization is favored over surgical revascularization owing to lower morbidity and mortality, high procedural success, and high patency rates over time. Most patients undergo balloon angioplasty and stenting of the iliac arteries, given the significantly higher long-term success rate with stenting compared with angioplasty alone.

In patients with femoral, popliteal, or tibial artery (infrainguinal) disease, the patency rates of endovascular revascularization are not as high as in the iliac arteries. Although infrainguinal disease was traditionally treated with angioplasty alone, the advent of atherectomy devices and nitinol stents has changed management. Recently, FDA-approved drug-coated angioplasty balloons and drug-eluting stents have demonstrated superior efficacy compared with standard angioplasty balloons in these patients.

The use of surgical revascularization has declined in the United States; however, patients with complex anatomy that may limit percutaneous procedural success and long-term patency (for example, long chronic total occlusions, multisegment disease) should still be referred for surgical revascularization. The two most common techniques of surgical revascularization are endarterectomy and surgical bypass.

Hybrid revascularization is the concomitant performance of surgical revascularization and endovascular revascularization in a single setting or finite time frame. Hybrid revascularization has increased in conjunction with the rise in endovascular revascularization; however, there are currently no clinical guideline recommendations for hybrid revascularization.

Acute Limb Ischemia

Acute limb ischemia is an infrequent but life-threatening manifestation of PAD. Classically, patients present with at least one of the “6 Ps”: paresthesia, pain, pallor, pulselessness, poikilothermia (coolness), and paralysis. Acute limb ischemia is most commonly caused by acute thrombosis of a lower extremity artery, stent, or bypass graft. Other causes include thromboembolism, vessel dissection (usually occurring periprocedurally), or trauma. The presentation of acute limb ischemia represents a true medical emergency; 10% to 15% of patients undergo amputation during initial hospitalization, and 20% of patients die within 1 year.

Anticoagulation, typically with unfractionated heparin, should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Specialists with expertise in revascularization should be consulted, and diagnostic angiography should be performed immediately to define the anatomic level of occlusion. In addition to surgical and endovascular revascularization options, catheter-directed thrombolysis improves outcomes in patients with acute limb ischemia.

Careful monitoring is required after limb reperfusion because of frequent reocclusion, limb edema, and the possibility of compartment syndrome. Signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome include severe pain, hypoesthesia, and leg weakness. If compartment syndrome occurs, surgical fasciotomy is indicated to prevent irreversible neurologic and soft-tissue damage.