Travel Medicine

- related: Infectious Disease ID

- tags: #id

Introduction

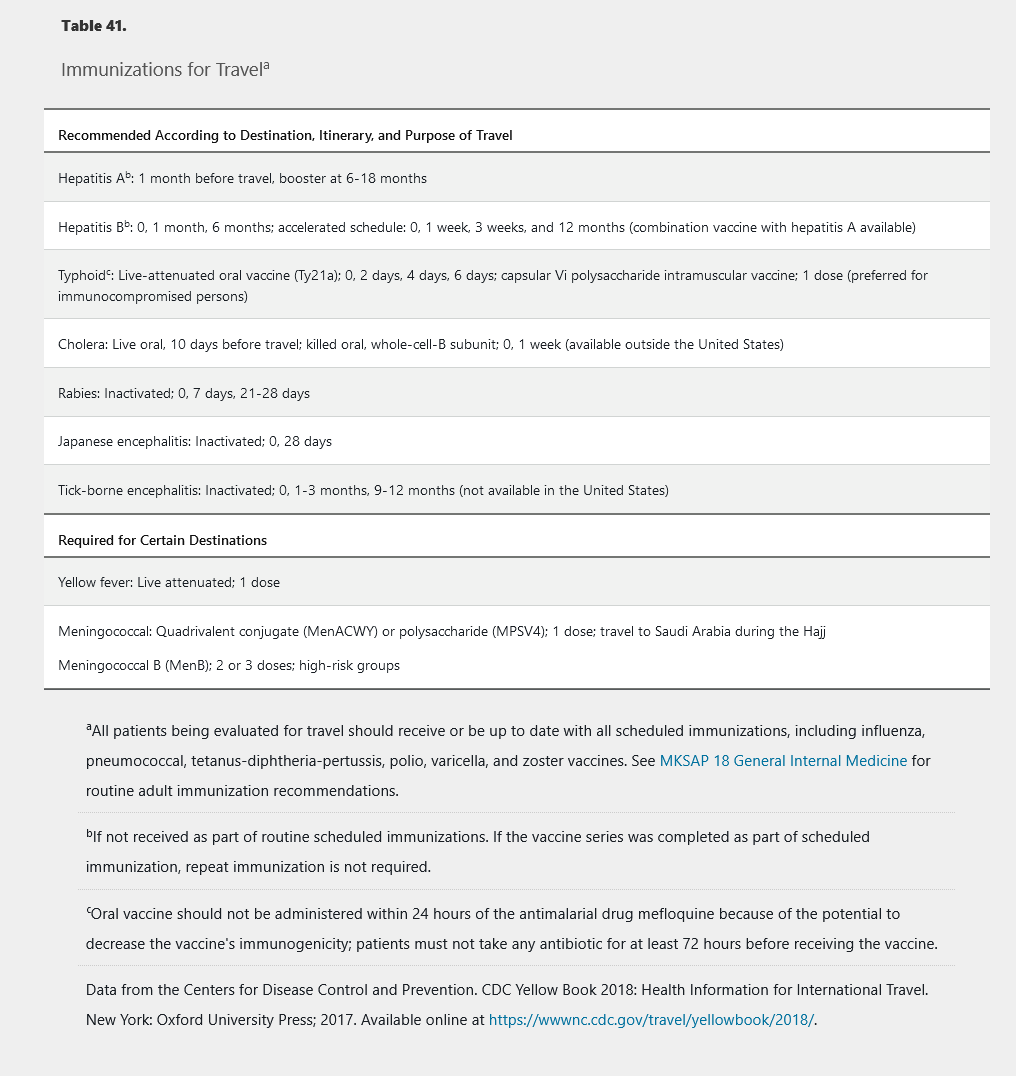

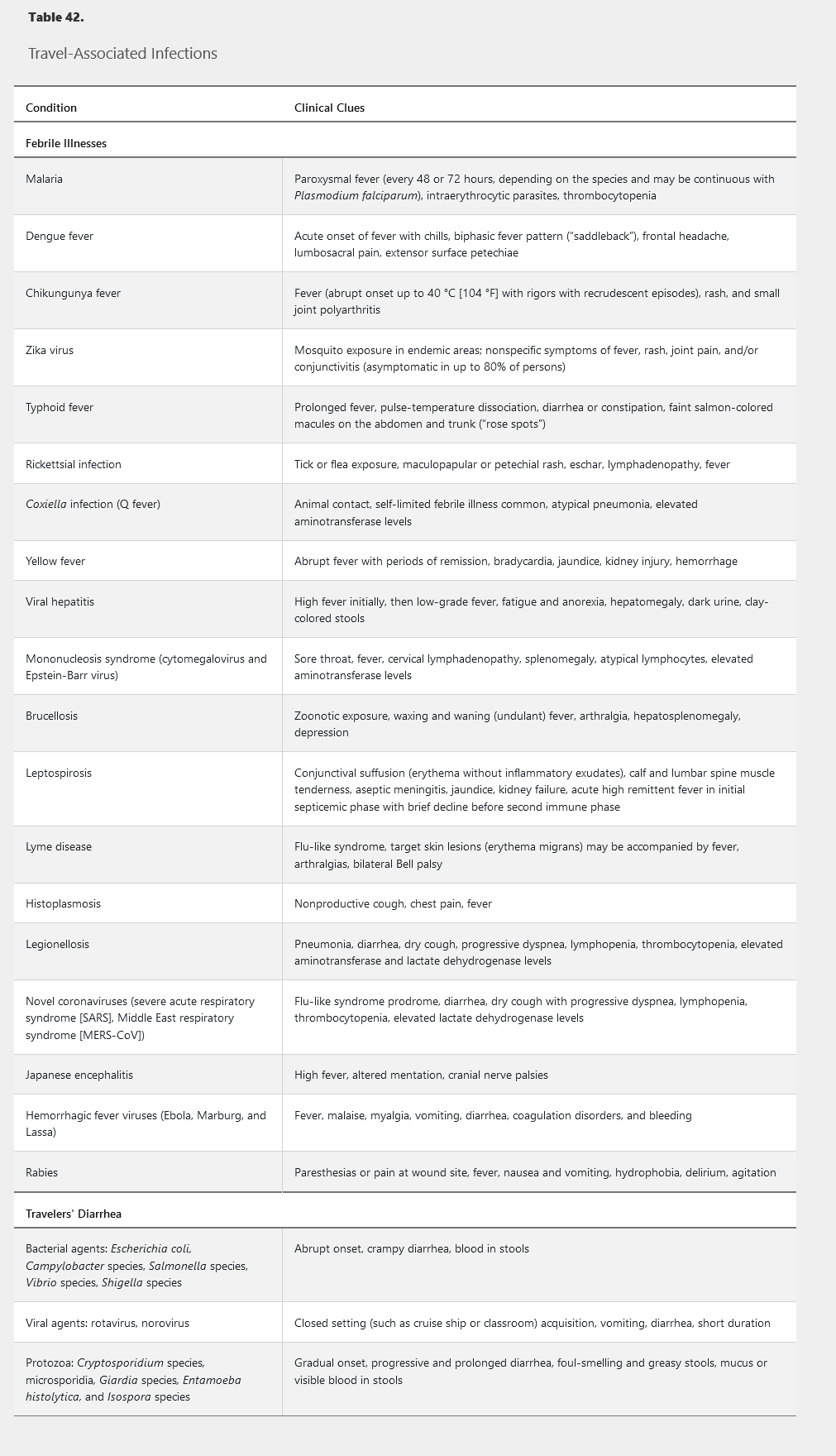

Pretravel consultation should occur no less than 4 to 6 weeks before departure. Regularly updated information by country is available on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) websites (http://www.cdc.gov/travel and http://www.who.int/ith). Travel-related illnesses (mostly febrile, diarrheal, respiratory, and cutaneous infections) are reported in 20% to 60% of returning travelers; many of these are vaccine preventable. Required and recommended pretravel immunizations are listed in Table 41. Potentially severe travel-associated infections are listed in Table 42, the most significant of which are reviewed here.

Malaria

Malaria is transmitted to humans by the female Anopheles mosquito. It is the most common cause of febrile illness in returning travelers, particularly from sub-Saharan Africa and large parts of Asia. Preventive measures include limiting outdoor exposure between dusk and dawn, using insecticide-impregnated bed nets and insect repellents containing 20% N-diethyl-3-methylbensamide (DEET), and using antimalarial chemoprophylaxis.

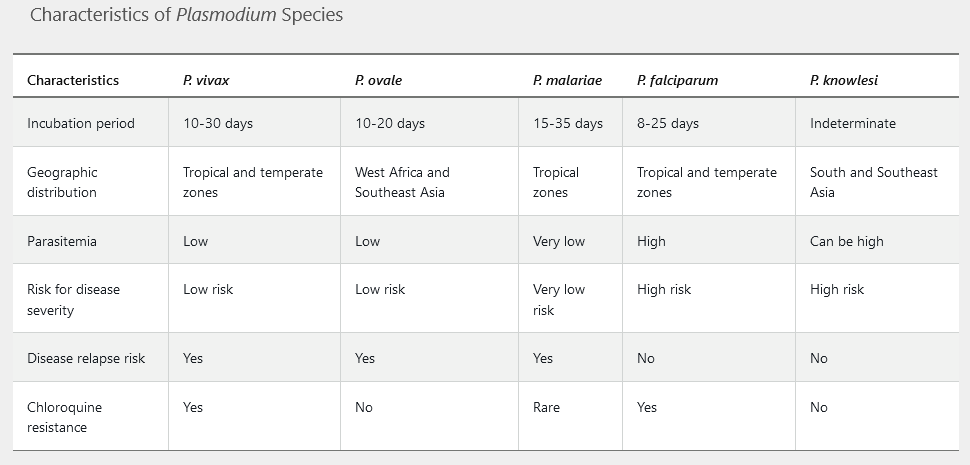

Incubation periods vary by species and range from 1 week to 3 months in semi-immune persons or those taking inadequate prophylaxis. Symptoms include fever (characteristically paroxysms in 48or 72-hour cycles), headache, myalgia, and gastrointestinal symptoms. More severe disease occurs with hyperparasitemia (5%-10% parasitized erythrocytes) leading to adherence in small blood vessels causing infarcts, capillary leakage, and multiorgan system dysfunction. Serious disease primarily occurs with Plasmodium falciparum; manifestations include mental status alterations, seizures, hepatic failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, brisk intravascular hemolysis, metabolic acidosis, kidney disease, hemoglobinuria, and hypoglycemia. Subsequently, patients may develop anemia, thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, and elevated aminotransferase levels. See Table 43 for specific features of the five Plasmodium species.

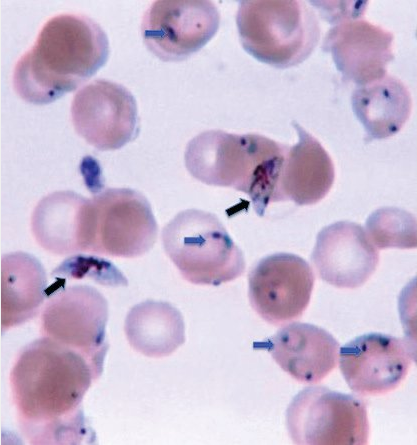

Diagnosis is made by identification of malarial parasites on the peripheral blood smear. Morphologic features help determine the specific species. Rapid tests that detect malaria antigens are available but may lack sensitivity and specificity. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serologic assays exist, although each has limitations.

It is critical to identify P. falciparum and P. knowlesi because of their potential for severe infection. The onset of malarial symptoms shortly after returning from travel to endemic zones, such as Africa, and recognition of a high level of parasitemia and distinctive morphologic characteristics (Figure 18) should raise suspicion for P. falciparum infection. P. knowlesi is an emerging human pathogen found in South and Southeast Asia; high levels of parasitemia may occur, and examination of the peripheral blood smear reveals all stages of the parasite.

Thin, often multiple rings (blue arrows) (signet ring) on the inner surface of young and old erythrocytes as well as banana-shaped gametocytes (black arrows) are distinctive morphologic characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum species.

Malarial chemoprophylaxis and treatment depend on possible drug resistance and individual contraindications to specific medications (Table 44 and Table 45). Additional detailed information about malaria is provided in the CDC Yellow Book or by calling the CDC malaria hotline (855-856-4713).

Typhoid (Enteric) Fever

Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi (A, B, and C) cause prolonged febrile and often serious infection (typhoid fever). Infection is acquired by consuming food or water contaminated by organisms shed in the stool of infected humans. Travel to South, East, and Southeast Asia (Indian subcontinent) and portions of sub-Saharan Africa pose the greatest risk of infection. Unlike other nontyphoidal Salmonella (see Infectious Gastrointestinal Syndromes), the causative agents of enteric fever are human-only pathogens. Oral and parenteral vaccines (see Table 41) afford temporary protective immunity in 50% to 80% of recipients.

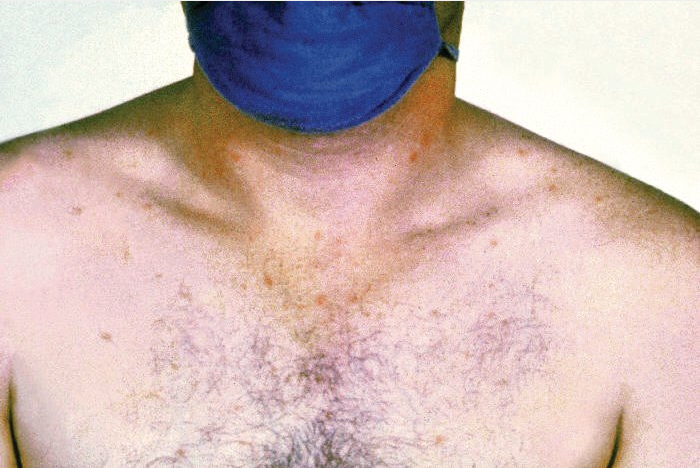

The gradual onset of fever with headache, arthralgia, myalgia, pharyngitis, and anorexia follows a 1to 2-week incubation period. Abdominal pain and tenderness can be accompanied by early-onset diarrhea, which may spontaneously resolve or become severe late in disease. One fifth of patients have constipation at diagnosis. In untreated illness, temperature progressively increases and may remain elevated (up to 40 °C, 104 °F) for 4 to 8 weeks. A pulse-temperature dissociation (relative bradycardia) and prostration are common. During the second week of illness, discrete, blanching, 1to 4-mm salmon-colored macules, known as rose spots (Figure 19) develop in crops on the chest and abdomen in about 20% of patients. Moderate hepatosplenomegaly, leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated aminotransferase levels are common. Secondary bacteremia may cause pyogenic complications such as empyema, muscle abscess, and endovascular infections. Intestinal hemorrhage or perforation may occur 2 to 3 weeks after infection onset. Encephalopathy occurs in more severe cases.

Rose spots on the chest of a patient with typhoid fever caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi.

Invasion of the gallbladder by typhoid bacilli may result in a long-term carrier state with shedding of organisms in the stool for more than 1 year. Those with gallstones and chronic biliary disease are at greatest risk.

Diagnosis is made through isolation of S. typhi or S. paratyphi from blood, stool, urine, or bone marrow; isolation success declines after the first week of illness. Rapid serologic tests are available to distinguish Salmonella enterica serotype typhi antibodies.

Antibiotic treatment decreases mortality and shortens the duration of fever. The emergence of antibiotic resistance in many geographic areas necessitates that in vitro susceptibility testing be performed on all clinical isolates. Ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolones, and azithromycin are preferred treatments. Dexamethasone has been shown to decrease mortality in severe illness, such as in patients with shock and encephalopathy. A 28-day course of ciprofloxacin is effective in eradicating chronic carriage, although cholecystectomy may be needed in cases of cholelithiasis.

Travelers’ Diarrhea

The most common travel-associated infection is diarrhea, defined by the sudden onset of three or more loose or watery stools per day with at least one additional gastrointestinal or systemic clinical sign or symptom (fever, cramps, nausea, abdominal pain, or blood in the stools). Risk factors, including geographic location (greatest in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America), type and duration of travel, and host characteristics, contribute to the 30% to 60% occurrence rate.

Most travelers’ diarrhea episodes occur within the first 2 weeks of travel. Episodes are usually self-limited, lasting approximately 4 days; however, life-threatening volume depletion or severe colitis with systemic manifestations can occur. Some travelers develop chronic diarrhea or a postinfective irritable bowel syndrome.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is the most common causative agent (see Table 42). Younger age, use of gastric acid–reducing medications, abnormal gastrointestinal motility or altered anatomy, O blood type, and other genetic factors increase risk. Immunocompromised travelers may experience more serious and protracted illness with typical pathogens and are more prone to infection with opportunistic infectious agents. Chronic gastrointestinal conditions (such as inflammatory bowel disease) do not increase risk of infection but do predispose travelers to more severe symptoms.

Pretravel advice includes avoiding consumption of tap water (through drinks, ice, or when brushing teeth), undercooked meats, unpasteurized dairy products, and fruits that are not peeled just before eating. Water disinfection can be accomplished by boiling for 3 minutes or by chemical means using chlorine and iodine. Two drops of sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or five drops of tincture of iodine per liter of water are equally effective. Commercial water filters are not as dependable.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea is effective but is generally not recommended because of the potential for adverse effects. Prophylaxis should be considered in persons with coexisting inflammatory bowel disease, immunocompromised states (including advanced HIV), and comorbidities that would be adversely affected by significant dehydration. Bismuth subsalicylate can be used to prevent diarrhea, but the doses required are inconvenient and can lead to salicylate toxicity. Evidence is insufficient to recommend the use of probiotics in the prevention or treatment of travelers’ diarrhea.

Fluid replacement is the mainstay of treatment. Antimicrobials reduce the duration of diarrhea by 1 to 2 days and are recommended when diarrhea is distressing or interferes with planned activities (Table 46). Self-treatment with a fluoroquinolone, azithromycin (preferred in South and Southeast Asia), or rifaximin is usually sufficient. Bismuth subsalicylate in large doses can be beneficial in decreasing the frequency and duration of diarrhea in milder cases. Antimotility drugs such as loperamide may be given as monotherapy in milder disease or in conjunction with antimicrobial therapy but should not be used in cases of dysentery or bloody diarrhea because of increased risk of colitis and colonic perforation.

Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, and Zika

Arboviruses are spread by arthropod vectors. Mosquitoes spread most travel-related arboviral diseases. Some arboviruses, such as yellow fever, are endemic throughout the tropics, and several countries require proof of vaccination before allowing entry by travelers. Other viruses, such as Japanese encephalitis, have more restricted geographic areas. The dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika arboviruses are all spread by Aedes species mosquitoes and will be discussed here (Table 47).

Dengue fever is the most prevalent arthropod-borne viral infection in the world. Endemic areas include Southeast Asia, the South Pacific, South and Central America, and the Caribbean. The incubation period is 4 to 7 days. Patients may be asymptomatic or present with an acute febrile illness associated with frontal headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, and arthralgia, with or without minor spontaneous bleeding. Gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms may predominate. Severe lumbosacral pain is characteristic. As the fever abates, a macular or scarlatiniform rash, which spares the palms and soles, may develop and evolve into areas of petechiae on extensor surfaces (Figure 20). Fever resolves after 5 to 7 days; however, some patients experience a second febrile period (saddleback pattern). A prolonged period of severe fatigue may follow. In patients with severe infection, life-threatening hemorrhage (dengue hemorrhagic fever) or shock may ensue, with liver failure, encephalopathy, and myocardial damage. This syndrome appears to be related to previous infection of a different serotype and is unlikely in travelers who have not had dengue fever previously. Abnormal laboratory findings include leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated serum aminotransferase levels.

Diagnosis of dengue fever is based on clinical suspicion in a patient who traveled to an endemic area and presents with fever and other typical signs, symptoms, and abnormal laboratory findings. Diagnosis is confirmed by serology (IgM and IgG) or reverse transcriptase PCR. Therapy is supportive. A live attenuated dengue vaccine was approved by the FDA in May 2019. However, it is for use only in persons aged 9 to 16 years. Recipients must have laboratory-confirmed previous dengue infection and live in an endemic area.

Historically, chikungunya virus was limited to Southeast Asia and Africa but has recently emerged in the Americas, with outbreaks in Central and South America and the Caribbean. No vaccine is available. Symptoms resemble dengue fever, including abrupt onset of fever (≥39.0 °C [102.2 °F]) and severe bilateral and symmetrical polyarthralgia, often involving the hands and feet. A maculopapular rash on the limbs and trunk is common. Rarely, central nervous system, ophthalmologic, hepatic, and kidney manifestations are present. Abnormal laboratory findings include lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated aminotransferase levels. Definitive diagnosis relies on serologic assays or detection of viral RNA by reverse transcriptase PCR testing. Disease is generally self-limited, resolving in 7 to 10 days. However, some patients may experience relapsing and chronic rheumatologic symptoms for months or even years. Symptomatic treatment includes NSAIDs and aspirin avoidance (risk of bleeding complications and potential risk of Reye syndrome in children).

Before the 2015 Zika virus epidemic in Central and South America, human infection occurred chiefly in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. More than 5600 infections have been reported in the United States since the epidemic, of which greater than 225 are presumed to be from local transmission (Florida and Texas) and 55 acquired by sexual or laboratory transmission. This flavivirus is closely related to dengue, yellow fever, and Japanese encephalitis viruses. Intrauterine and perinatal maternal-fetal spread and sexual transmission from an infected male partner are other less common modes of transmission. An estimated 18% of those infected demonstrate clinical symptoms, which are similar to dengue and chikungunya virus infections, with the additional finding of conjunctivitis in most Zika infections. Most patients recover uneventfully after a mild illness lasting about 1 week, but some develop Guillain-Barré syndrome. Of most concern are risks to fetal development in pregnant women infected with Zika, including microcephaly, other severe brain and eye defects, and impaired growth and fetal loss. Women who are pregnant must be advised against travel to areas where Zika virus is known to be present. Likewise, women and men who are planning to conceive in the near future should consider avoiding nonessential travel to areas with risk of Zika infection; it is recommended couples wait to conceive until at least 3 months (for men) or 8 weeks (for women) after the last possible Zika virus exposure or from the onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Those not planning to conceive should use condoms for all forms of sexual activity together with their chosen birth control method or abstain from sex if Zika virus transmission is a concern.

All pregnant women should be assessed for possible Zika exposure, and those who return from areas with outbreaks should be screened for evidence of infection. For symptomatic, nonpregnant patients, nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for dengue and Zika virus should be performed on serum collected within 7 days of symptom onset. IgM antibody testing should be performed on NAAT-negative serum or serum collected more than 7 days after symptom onset. For symptomatic pregnant women, serum and urine specimens should be collected as soon as possible for dengue and Zika virus NAAT and IgM antibody testing. Women who are pregnant and those who are planning to conceive should consult the CDC website for the most updated information when considering travel. No specific medications are available for treating Zika virus. Active vaccine development is ongoing.

RNA nucleic acid amplification testing for the presence of Zika virus in serum and urine has a greatly diminished sensitivity if performed more than 2 weeks after symptomatic or asymptomatic exposure. In this case, Zika virus IgM antibody testing is preferred.

Hepatitis Virus Infections

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is acquired through ingestion of food and water contaminated with fecal waste from another infected human in geographic areas with poor sanitation practices. Travel to Central and South America, Mexico, South Asia, and Africa poses the greatest risk of infection (for further information, see MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology).

Hepatitis A vaccination is recommended for persons traveling to developing countries who are not already immune (see Table 41). Protective antibody titers develop within 2 to 4 weeks in almost 100% of healthy recipients. A booster dose is given 6 to 12 months after the initial injection and provides protection for at least 10 years. Serum immune globulin is indicated for persons aged 12 months or younger and for those who decline vaccination or are allergic to its components. It has also been recommended for immunocompromised persons (who are less responsive to hepatitis A vaccine) and patients with chronic liver disease. Concurrent administration of hepatitis A vaccine and immune globulin is no longer recommended for those planning to depart within 2 weeks.

The risk for travel-associated acquisition of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is low. Previously unvaccinated persons traveling as health care workers, seeking medical care, or likely to engage in sexual activity with local residents in countries where HBV is prevalent warrant pretravel vaccination. Persons with insufficient time before travel to receive the standard three-dose/6-month vaccination series can complete an accelerated vaccination schedule (0, 7, and 21-30 days); these persons require a booster dose at 12 months to ensure long-term protection. A combined hepatitis A/B vaccine is also available for this rapid three-dose schedule.

No vaccine prevents hepatitis C virus infection, and immune globulin offers no protection (see MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology).

Rickettsial Infection

Rickettsial infections occur worldwide. They usually belong to the typhus or spotted fever groups and are transmitted by small vectors (fleas, lice, mites, and ticks). Outbreaks have been associated with war and natural disasters and are promoted by suboptimal hygiene conditions and tick infestation. Rickettsia typhi is prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. Rickettsia prowazeki is the only rickettsial species transmitted by human body lice and has a worldwide distribution.

Fever is the most common presenting symptom; African tick typhus (Rickettsia africae) is second only to malaria as the cause of febrile illness in those who have journeyed to Africa, especially South Africa. Clinical presentation also includes headache, malaise, conjunctivitis, and pharyngitis often accompanied by a maculopapular, vesicular, or petechial rash. Following the bite of an infected tick or mite, an eschar with regional lymphadenopathy develops at the site of inoculation with R. africae, Rickettsia conorii, and Orientia tsutsugamushi. Endothelial damage in the microcirculation leads to increased vascular permeability and is the hallmark of rickettsial infections, with extensive vasculitic-appearing lesions. Severe complications may include shock, meningoencephalitis, and significant damage to the kidneys, lungs, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Recrudescent attacks designated Brill-Zinsser disease are known to occur months and even years later.

Diagnosis is confirmed by PCR, immunohistochemical analysis of tissue samples, or culture during the acute stage of illness before antibiotics are initiated. Confirmatory serologic assays often do not detect antibodies until the convalescent phase of illness, limiting their utility with acute disease. When clinical suspicion is high, empiric therapy is warranted. The treatment of choice for all rickettsial infections is doxycycline for 7 to 10 days.

mediterranean Spotted Fever

Mediterranean spotted fever is one of the most severe forms of the spotted fever group of rickettsial diseases likely to be contracted during international travel. Signs and symptoms of illness usually begin following an incubation period of 2 to 14 days after a tick bite, which frequently goes unnoticed. The risk of infection is greatest in northern and southern Europe but also occurs in Africa, India, and the Middle East. Characteristically, fever, myalgia, and headache mark the onset of infection followed shortly by the appearance of a maculopapular and oftentimes petechial rash, generally beginning on the ankles and wrists and typically involving the palms and soles. A distinct eschar (shown) is classically present at the site of inoculation along with the development of localized regional lymphadenopathy. Disease is usually mild to moderate; however, vascular dissemination can lead to severe complications, of which neurologic manifestations are the most common. Laboratory findings are nonspecific, but diagnosis may be aided by polymerase chain reaction and serologic assays. A 7to 10-day course of doxycycline is the treatment of choice.

Brucellosis

Human brucellosis may follow ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products or undercooked meat, by direct contact with fluids from infected animals through skin wounds or mucous membranes, or by inhalation of contaminated aerosols. Brucella is present in animal reservoirs worldwide, but the highest prevalence is found in the Mediterranean countries, Balkans, Persian Gulf, Middle East, and Central and South America. Brucella melitensis (from sheep and goats) has the highest pathogenicity and is the leading cause of human brucellosis.

After a variable incubation period, patients develop fever, myalgia, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, and night sweats. Focal infection may occur, commonly affecting the central nervous system and osteoarticular, cardiovascular, and genitourinary systems. Depression is frequent. Hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy may be apparent on physical examination with granuloma formation in reticuloendothelial tissues and organs. Disease relapse and chronic infection may occur owing to persistent foci of infection or inadequate antibiotic treatment.

Diagnosis relies on isolating the organism from cultures of blood, bone marrow, other body fluids, or tissue. The serum agglutination test is the most widely used available serologic test. An initial elevated titer of 1:160 or greater or demonstration of a fourfold increase from acute to convalescent titers is considered diagnostic. The Rose Bengal slide agglutination test, if available, is a convenient, simple, rapid, and sensitive point-of-care screening test.

The treatment of choice for uncomplicated brucellosis is a combination of doxycycline, rifampin, and streptomycin (or gentamicin), often given for several weeks. Neurobrucellosis requires several months of combined ceftriaxone, doxycycline, and rifampin.