aerospace industry is associated with berylliosis

- related: Occupational Lung Disease

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

Beryllium is a rare light metal extracted from beryl ore. With its high melting point and low density, it is suited well for heat shielding, rotational blades (because of resistance to the heat of friction), radiograph tubes, parts for microwave equipment, and certain parts of nuclear reactors. Cohorts of workers making dental prostheses and case descriptions of dental technicians developing chronic berylliosis have also been reported.

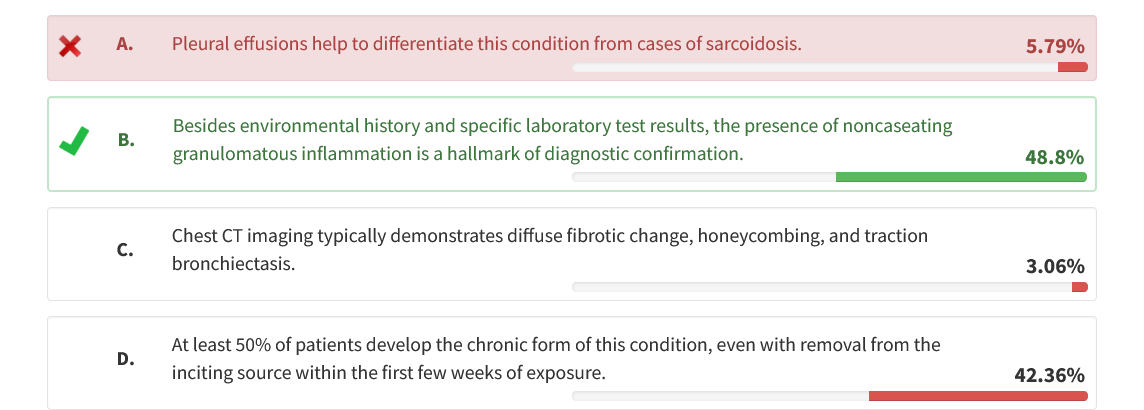

The clues provided of occupational exposure to heat-resistant and presumably lightweight parts used in the aerospace industry with radiographic features of sarcoidosis are suggestive of berylliosis. In the case of suspected chronic berylliosis, the presence of noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in conjunction with a compelling occupational and environmental history and beryllium lymphocyte transformation test results showing sensitization are the cornerstones of a confirmatory diagnosis.

Acute exposures often appear as an irritant reaction to the mucosal membranes and can result in acute pneumonitis. Chronic berylliosis refers to long-term respiratory changes encountered with repeated exposure to the metal and is more of a granulomatous disease. Berylliosis is not typically associated with other systemic effects such as that found in cases of sarcoidosis (eg, skin lesions, eye lesions, and cardiac arrhythmias).

Although thanks to increased regulatory rules and improved environmental hygiene techniques, with implementation of effective personal protective equipment, the prevalence of chronic berylliosis has declined significantly overall, it remains problematic, especially for certain smaller businesses that have not necessarily enforced or required use of personal protective equipment or engineering controls to reduce the concentration of potential exposures.

Chest radiographs may be normal or demonstrate bilateral hilar adenopathy or parenchymal abnormalities such as dense parenchymal nodules or ground-glass, linear, or alveolar opacities. The parenchymal abnormalities may be diffuse or occasionally demonstrate upper lobe predominance. Pleural thickening may be observed adjacent to areas of dense subpleural parenchymal nodules, but pleural effusions are uncommon.

High-resolution CT (HRCT) scans are more sensitive than plain chest radiographs for identifying the changes of chronic beryllium disease, although HRCT scans may be normal in up to 25% of patients with biopsy-proven chronic berylliosis. The HRCT findings include parenchymal nodules of varying sizes, thickened septal lines, ground-glass opacities, and adenopathy involving the hilum or mediastinum. Hilar lymphadenopathy develops later in the course of the disease compared with sarcoidosis. Pneumothorax has been reported but is uncommon. Chronic berylliosis is often mistaken for sarcoidosis because the radiographic presentation is similar and the occupational history is often omitted by clinicians in diagnostic considerations. Diffuse fibrotic change, honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis are not features seen with chronic berylliosis.

Latency is often noted from months to as long as 10 years, but unlike other occupationally related lung conditions affecting the parenchyma, such as the pneumoconioses, asbestosis, and silicosis, which have a latency of 2 to 3 decades, chronic berylliosis has a much shorter latency time frame. Long-term forms of beryllium exposure have a variable clinical course, with cough, fever, night sweats, and fatigue being the most common symptoms.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidelines set the permissible exposure limit for beryllium at 0.2 μg/m3 averaged over 8 h or less than 2 μg/m3 over a 15-min period. It is an incurable occupational lung disease, but symptoms can be treated and often mitigated. With removal from the exposure and treatment using corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive agents, most patients experience recovery, although up to 25% go on to develop chronic berylliosis despite removal from the known source.1