asbestosis

- related: Occupational Lung Disease

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

- pleural plaques

- benign pleural effusion

- pleural thickening

- rounded atelectasis

- bronchogenic carcinoma

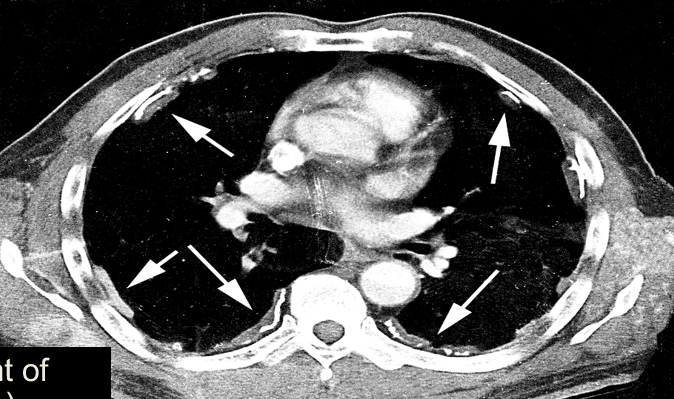

- mesothelioma

- BAPE benign asbestos related pleural effusion

Occupations that involve work in and around boilers and brake linings or work in the shipping industry are commonly associated with exposure to asbestos insulation or other asbestiform products.

For example, firefighters, construction workers, industrial and power plant workers, brake mechanics, and shipyard workers have traditionally been noted to handle asbestos-containing materials in clinically relevant volumes and are at greatest risk for development of asbestosis. An automobile mechanic working in a brake servicing department would be more likely to develop asbestosis as opposed to silicosis.

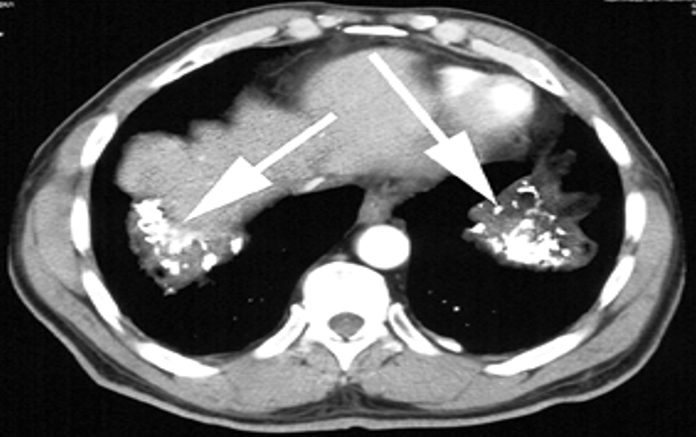

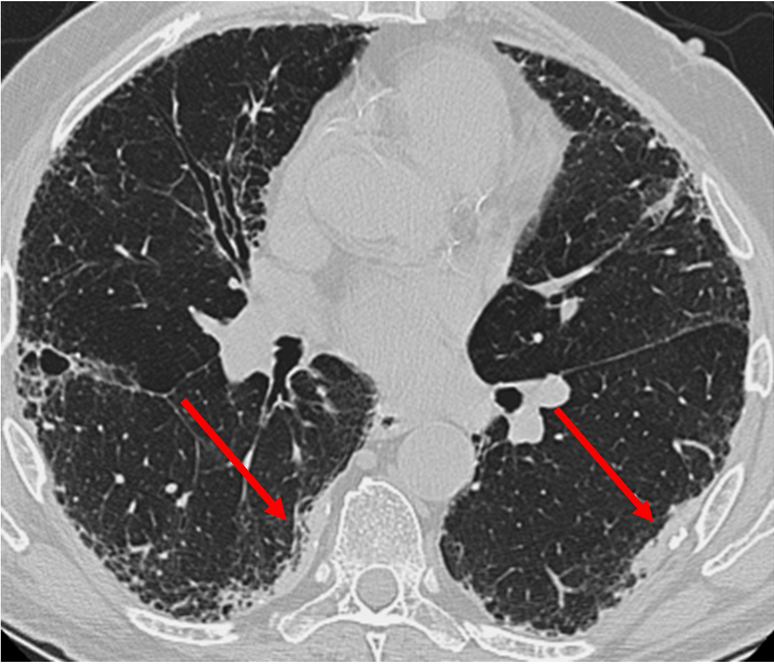

Asbestosis is a general term for a heterogeneous group of hydrated magnesium silicate minerals that may be inhaled and displaced by various means to lung tissue, resulting in a spectrum of diseases including cancer and disorders related to inflammation and fibrosis. Common radiographic findings in asbestosis include honeycombing and thickening of septa and interlobular fissures suggestive of interstitial fibrosis, diffuse pleural thickening, parenchymal bands, rounded atelectasis, and pleural plaques. Poorly defined centrilobular nodules and ground glass opacification are seen more commonly in hypersensitivity pneumonitis, while parenchymal congestion and transudative effusions may be seen with heart failure or volume overload. Cavitary lesions involving the pulmonary apices are not associated with asbestosis.1

Asbestos-Related Lung Disease

Asbestos includes a group of minerals that, when crushed, will break into fibers. These fibers are chemically heterogeneous hydrated silicates that are used in industry because of their high tensile strength, heat resistance, and acid resistance. In the past, asbestos fibers were widely used in insulation, brake linings, flooring, cement paint, and textiles. Because of the known toxicities associated with asbestos, these compounds are used far less frequently today.

Asbestos-associated diseases have a prolonged latency period (15 to 35 years), resulting in continued identification of new cases despite the decreased use of asbestos in the United States. Continued exposures within the United States and the developed world occur through updating, demolition, and abatement of older construction. Asbestos exposure remains an occupational hazard for workers in developing nations.

Risk Factors

Duration and extent of exposure are key risk factors for the development of disease. Asbestos-related lung diseases are common in mine workers who procure the asbestos and in industries that make use of the products. In the United States, workers in construction, naval shipyards, and the automotive service industries are particularly at risk. Exposure is also possible in areas where manufacturing of asbestos leads to environmental contamination. Similarly, there are reports of people who develop asbestos-related lung diseases after exposure to asbestos dust from family members working in an asbestos-related industry.

Pathophysiology

Inhaled asbestos fibers deposit deep within the lung, reaching airway bifurcations; respiratory bronchioles; and the alveolus, where they promote alveolitis. Type I alveolar epithelial cells take up the fibers, which migrate to the interstitium. Lymphatic channels transport asbestos fibers to the pleural surface. Although activated macrophages phagocytose and remove fibers, remaining fibers stimulate the macrophage to produce inflammatory mediators. These and other cell mediators stimulate fibroblast proliferation and chemotaxis, resulting in collagen deposition and development of fibrosis.

Asbestos exposure increases the risk for development of lung cancer regardless of smoking status, but the risks are substantially higher in smokers. This risk of cancer is apparent when any form of asbestos-related lung disease is present; however, for those with a history of asbestosis (that is, diffuse parenchymal lung disease secondary to asbestos), the risk of lung cancer is 36 times higher than in those with no history of smoking. Smoking cessation is essential. Findings of parietal pleural calcifications or plaques on chest radiograph should alert the clinician to the possibility of asbestos exposure. Although most patients with pleural plaques are asymptomatic, the most common symptom is exertional dyspnea. Additional evaluation including evaluation for lung cancer or mesothelioma should be considered.

- silocosis: sand blasting, rock quarries

- asbestosis: ship yards, construction, mesothelioma, barbell bodies

- berylliosis: aeronautics, electronics

- pneumoconiosis: coal worker lung, caplan syndrome/arthalgia

- talc exposure

- bird’s lung disease: HP2