biliary leak after cholecystectomy

- related: GI gastroenterology

- tags: #literature #GI

Collection bottles with typical, green-colored fluid drained via large-volume paracentesis in patient with choleperitoneum.

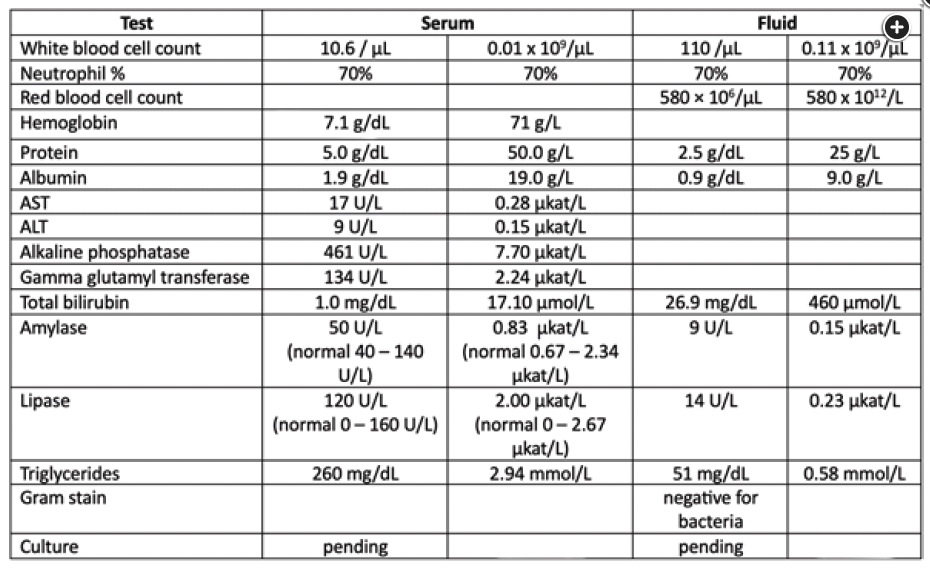

The presence of increasing volume of ascites in the first few days after cholecystectomy, high bilirubin level in the ascites fluid (>6 mg/dL [102.62 µmol/L]), and fluid-to-serum bilirubin concentration ratio greater than 1 indicate the presence of a biliary leak into the peritoneum (choice D is correct).

Biliary leaks complicate approximately 1% to 4% of open cholecystectomies. Patients with biliary leaks typically develop abdominal discomfort and distention—and, occasionally, fever or jaundice—2 to 10 days after surgery. Less frequently, choleperitoneum may lead to peritonitis either via chemical irritation or due to secondary infection. Peripheral leukocytosis may be present, and elevations of alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyltransferase are commonly seen. Transaminase levels are often normal. Serum bilirubin levels may be normal or slightly elevated as the body reabsorbs the third-spaced bile over time.

The presence of ascites can be confirmed by ultrasound. If an operative drain was left in place, it may drain bilious fluid. Alternatively, fluid can be removed via paracentesis for sampling and for symptomatic relief if there is a large volume of ascites fluid. The fluid of choleperitoneum is typically dark green, or bilious, in appearance (Figure 2). Laboratory testing of the fluid can confirm the presence of bile via the criteria above. Sometimes cholescintigraphy (also known as hepatic iminodiacetic acid scan) may be used to demonstrate a leak from the remaining biliary tree into the peritoneal cavity. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be diagnostic, by confirming a leak, as well as therapeutic, via sphincterotomy and/or stent placement that reduces the resistance to flow of bile into the duodenum, diverting it away from the leak. Other treatment options include percutaneous drainage for management of ascites. Sometimes small leaks can be self-limiting. When less invasive measures fail, operative exploration may be needed. The management of biliary leaks usually requires a multidisciplinary approach involving surgery, interventional gastroenterology, and interventional radiology.

Choleperitoneum may also be associated with perforation of proximal bowel, pancreatitis, or rupture of pancreatic pseudocysts. In these instances, the amylase level in ascites fluid is usually high (often >1,000 U/L [16.7 µkat/L]), whereas in choleperitoneum due to direct leak from the biliary tree, the fluid amylase level is not elevated, as bile has a low concentration of amylase. This allows the etiology of choleperitoneum to be distinguished.

Secondary bacterial peritonitis refers to infection in the peritoneal space from an identifiable source, most frequently a perforated viscus. The patient in this question did have a perforated gall bladder from blunt trauma during a motor vehicle accident, but this was identified and surgically treated via cholecystectomy. While infection can complicate abdominal surgery postoperatively, it most frequently presents as intraabdominal abscess associated with prolonged ileus. Patients with secondary bacterial peritonitis are often sicker, with signs of infection and peritonitis, including sepsis and shock. Mortality is high without surgical management. Imaging may reveal fluid and free air in the abdomen in the setting of bowel perforation. Ascites fluid, if sampled, may be green in color but can also be turbid, milky, brown, or feculent. Diagnostic criteria require an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of greater than 250/µL (0.25 × 109/L) in the presence of an intraabdominal source of infection. Gram stain and cultures may be positive and are typically polymicrobial (choice A is incorrect).

The spleen is one of the most frequently injured organs in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma. While the presentation and management can vary based on extent of splenic injury, at least some amount of bleeding is typical. Bleeding may be localized (around the spleen, under the capsule, or in the parenchyma) or manifest as hemoperitoneum and even hemorrhagic shock in the setting of a “shattered” spleen. While ultrasound and CT imaging have largely replaced diagnostic peritoneal lavage, if the abdominal fluid is sampled, it would be consistent with hemoperitoneum (either blood or bloody appearing, with fluid RBC count >50,000 × 106/µL [50,000 × 1012/L]). This patient has an inconsistent timeline (development of new large-volume ascites several days after surgery), discordant laboratory results (stable hemoglobin despite aspiration of over 5 L of fluid from the abdominal cavity), atypical appearance of fluid (green/bilious), and incompatible fluid analysis (fluid RBC count <50,000 × 106/µL [50,000 × 1012/L]) for this to be splenic rupture or shattered spleen (choice B is incorrect).

Blunt abdominal trauma or surgery can result in disruption of lymphatic channels, causing triglyceride-rich lymphatic fluid to leak into the peritoneal space. This results in chylous, milky-appearing ascites. Diagnosis of chylous ascites requires fluid triglyceride level greater than 110 mg/dL (1.24 mmol/L); more typically, it is higher than 200 mg/dL (2.26 mmol/L) (choice C is incorrect). In addition to trauma, chylous ascites can be seen in patients with malignancy including lymphoma, certain infections (eg, filariasis and tuberculosis), and in conditions with high caval pressures, such as cirrhosis and right heart failure, which cause elevated pressures and even rupture of abdominal lymphatics. Pseudochylous ascites, which appears milky but is not rich in triglycerides, can be seen in patients with bacterial peritonitis or perforated bowel. Triglyceride level greater than 110 mg/dL (1.24 mmol/L) and the presence of chylomicrons are hallmarks of chylous ascites and distinguish it from pseudochylous ascites.12345

A 52-year-old patient who was in a motor vehicle accident underwent urgent laparotomy and cholecystectomy for management of a ruptured gall bladder. He was recovering well until the fourth postoperative day, when he developed abdominal distention. The following day, the abdominal distention was worse, and he had mild abdominal pain. He was afebrile with a BP of 112/70 mm Hg and heart rate of 85/min. There was tenderness to deep palpation in the right hypochondrium and dullness in bilateral flanks. Ultrasound confirmed the presence of a large volume of ascites. Paracentesis was performed with removal of approximately 5 L of dark green fluid. Results of laboratory testing are shown in Figure 1.

Which is the most likely etiology of ascites in this patient?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Blank J, Anderson E, Mansoor AM. Biliary Ascites. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(12):3190. PubMed ↩

-

Cárdenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(8):1896-1900. PubMed ↩

-

Runyon BA. Ascitic fluid bilirubin concentration as a key to choleperitoneum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9(5):543-545. PubMed ↩

-

Tinkoff G, Esposito TJ, Reed J, et al. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale I: spleen, liver, and kidney, validation based on the National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(5):646-655. PubMed ↩