small bowel mesenteric ischemia

- related: GI gastroenterology

- tags: #literature #icu

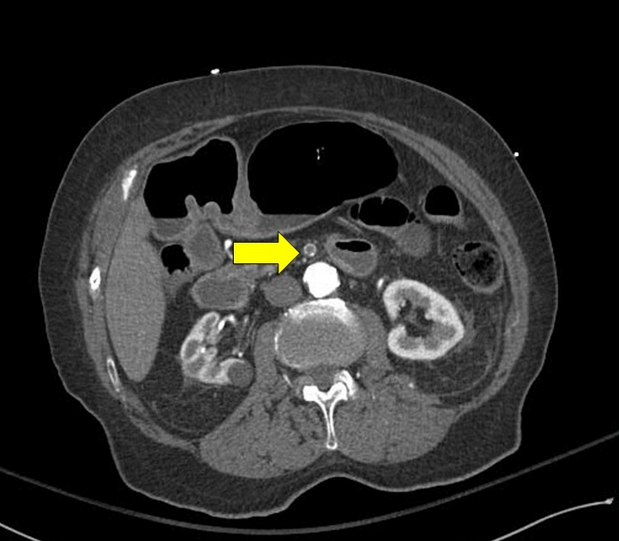

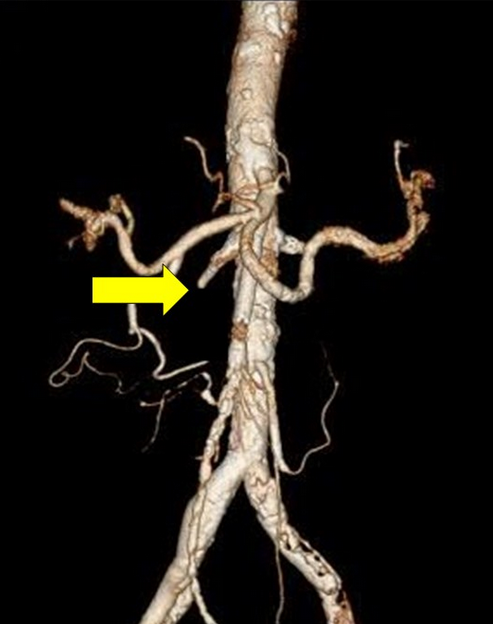

Mesenteric ischemia often presents with vague and nonspecific symptoms and requires a high index of suspicion to avoid delayed diagnosis. The CT angiogram (Figure 4) demonstrates acute thrombosis within the patient’s known superior mesenteric artery stent, with complete obstruction to flow more easily seen on the three-dimensional reconstruction (Figure 5). Emergent exploratory laparotomy is the most appropriate next step to assess bowel viability prior to consideration of revascularization. In this case, extensive small bowel ischemia was present (Figure 6), which progressed to full-thickness necrosis despite successful intraoperative revascularization over the next 24 h. The patient was subsequently transitioned to comfort care.

CT angiogram demonstrating thrombosis within the mesenteric stent.

3D reconstruction demonstrating an acute cut-off at the level of the mesenteric thrombus.

Acute mesenteric ischemia is most commonly associated with arterial embolism or thrombosis, mesenteric venous thrombosis, or nonobstructive mesenteric disease in the setting of critical illness. The typical presentation is an elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, complaining of severe abdominal pain out of proportion to clinical exam. Vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal distension, and hematochezia are also common symptoms. Patients with acute mesenteric ischemia from arterial embolism often have a history of paroxysmal or new-onset atrial fibrillation or a recent history of myocardial infarction or cardiac or vascular surgery. Patients with arterial thrombosis, as in this case, often have chronic mesenteric ischemia or extensive peripheral vascular disease. Venous thrombosis presents more insidiously, and patients commonly have recent venous thromboembolism, abdominal surgery, or a hypercoagulable state. Nonobstructive acute mesenteric ischemia can be seen in the critically ill patient with hypoperfusion, shock, and significant vasopressor requirements in the setting of significant, fixed mesenteric artery stenosis.

Small bowel ischemia typically causes crampy, periumbilical pain, and abdominal tenderness is usually minimal until transmural ischemia and peritonitis develop. Leukocytosis, worsening metabolic acidosis, and elevated lactate are common but nonspecific findings, and findings of pneumatosis (seen in the left upper quadrant of Figure 1), thumbprinting, free air, and portal venous gas on abdominal plain radiographs are both difficult to identify and late findings. CT mesenteric angiography is the gold standard, offering a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 95% in one meta-analysis.

This case offers the opportunity to contrast acute mesenteric ischemia with chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI), the most common vascular disorder involving the bowel. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of this condition, and identification of mesenteric artery stenosis in this era of high-volume cross-sectional imaging is common. Interestingly, despite severe mesenteric stenosis (>50%) being identified in almost 20% of the elderly, less than 1% of these patients develop symptoms requiring intervention due to the extensive collaterals present in most adults. Other causes of CMI include aortic dissection, fibromuscular dysplasia, or vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa, thromboangiitis obliterans). Women account for >70% of CMI cases and typically present with chronic postprandial abdominal discomfort, a fear of eating, and significant weight loss. Other complaints can include vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and lower GI bleeding. Diagnostic testing includes duplex ultrasound or noninvasive CT or magnetic resonance angiography. Symptomatic patients often have significant obstruction of two or more of the three main mesenteric vessels (celiac, superior, and inferior mesenteric arteries). Invasive digital subtraction angiography can be helpful in challenging cases and offers the ability to measure translesional pressure gradients in areas of questionable severity. Patients with symptoms and critical stenosis (≥70%) in multiple arteries are typically referred for percutaneous revascularization with angioplasty and stent placement due to the significant perioperative cardiac mortality following open surgical procedures. Although the short-term risk of complications following percutaneous revascularization is low, long-term restenosis rates are higher than surgery.

Systemic anticoagulation alone is inadequate to provide early and definitive mesenteric reperfusion, which is essential to bowel survival in this setting. Upper endoscopy and mesenteric angiography will not add further diagnostic information given the compelling CT angiogram findings, and vascular intervention should not be performed without an examination of bowel viability to determine if the procedure will be of benefit.123456

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Acosta S. Mesenteric ischemia. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015;21(2):171-178. PubMed ↩

-

Carver TW, Vora RS, Taneja A. Mesenteric ischemia. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):155-171. PubMed ↩

-

Cudnik MT, Darbha S, Jones J, et al. The diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(11):1087-1100. PubMed ↩

-

Schoots IG, Koffeman GI, Legemate DA, et al. Systematic review of survival after acute mesenteric ischaemia according to disease aetiology. Br J Surg. 2004;91(1):17-27. PubMed ↩

-

White CJ. Chronic mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis and management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;54(1):36-40. PubMed ↩