Strongyloidiasis stercoralis symptoms

- related: Infectious Disease ID

- tags: #literature #id

This patient from the Dominican Republic has a raised, erythematous, linear rash with significant eosinophilia, raising suspicion for strongyloidiasis.

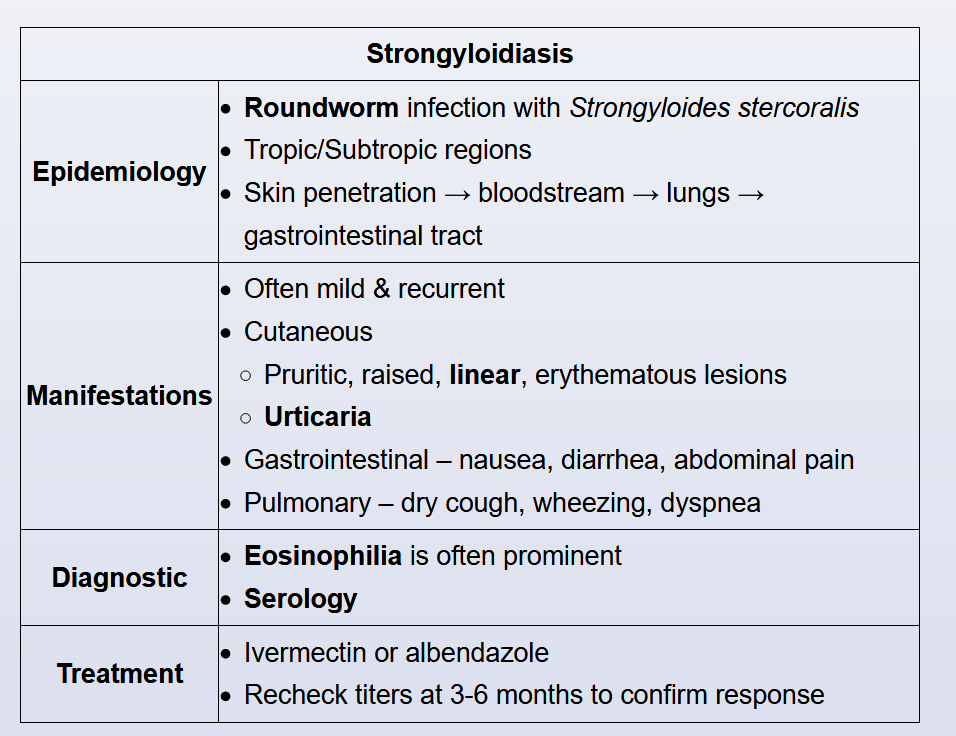

Strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis, a roundworm endemic to tropical and subtropical regions where prevalence can approach 25%. Inoculation occurs when human skin contacts filariform larvae in soil contaminated by human feces (from an infected host). After cutaneous penetration, the larvae migrate hematogenously to the lung where they enter the alveoli, ascend the tracheobronchial tree, and are swallowed. This results in chronic infection of the duodenum and jejunum with periodic autoinoculation through the perianal skin.

Symptoms reflect the worm lifecycle, and patients often have mild manifestations that wax and wane for years. Cutaneous findings include urticarial skin reactions and periodic erythematous, raised tracks on the buttocks or thighs (secondary to autoinoculation); gastrointestinal (eg, nausea, diarrhea, pain) and pulmonary (eg, dry cough, wheezing) symptoms may also occur. Laboratory results usually show prominent eosinophilia.

Stool examination has low sensitivity (<50%) for diagnosis due to periodic shedding of organisms; diagnosis is typically confirmed with serology. Treatment with ivermectin or albendazole is usually curative, but repeat serologies should be performed at 3-6 months as treatment failures can occur.

This patient has polymicrobial bacteremia with enteric organisms without an obvious source, urticaria, and recent corticosteroid use and has time spent in part of the world where Strongyloides is endemic. He should be tested for strongyloidiasis (choice C is correct).

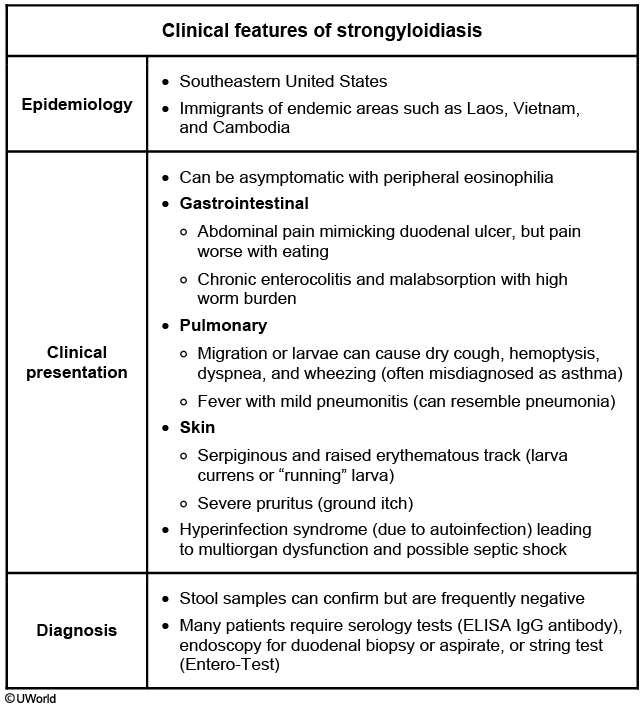

Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasitic infection endemic in many parts of the world, especially in tropical and subtropical climes, and is increasingly prevalent in the United States. Strongyloidiasis can be asymptomatic, and the organisms can persist in the human host for years—or even decades—after exposure. Parasites are present in soil and feces, and they enter the body via the skin, penetrate the venous circulation, pass through the lungs, and are aspirated into the gastrointestinal tract. They persist in the body for a long time via autoinfection, wherein the parasites penetrate the intestinal submucosa, reenter the circulation, and follow the same path back to the gastrointestinal tract. The process of the parasites passing from the gut into the blood creates opportunity for other enteric organisms to enter the bloodstream as well. An amplified process of autoinfection with higher parasite burden, called hyperinfection, can occur in patients who are immunocompromised or on immunosuppressive medications, particularly corticosteroids. Hyperinfection increases the risk of bacteremia and of disseminated strongyloidiasis, in which larvae can be found in many organs. Other symptoms of strongyloidiasis include abdominal pain, discomfort, nausea, and vomiting. Pulmonary migration of parasites can present as cough, wheezing, pneumonitis, and hemoptysis. Skin involvement is common. Larva currens is a migratory rash along the path of the movement of larvae in the skin; while it is pathognomonic for strongyloidiasis, it occurs infrequently. Periumbilical purpura indicates disseminated disease. Most commonly, patients develop an urticarial rash, as in this case. Most patients with strongyloidiasis have peripheral eosinophilia, although it can be absent in the setting of corticosteroid use.

The combination of polymicrobial bacteremia with enteric organisms in the setting of recent steroid use (or other immunosuppression) and presence of respiratory, gastrointestinal, or skin findings in a patient from an endemic area should trigger evaluation for strongyloidiasis. Of note, Streptococcus gallolyticus is part of group D streptococci (Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus equinus group); in addition to evaluation for strongyloidiasis, patients should be screened for colon cancer.

The diagnosis of strongyloidiasis is usually suspected clinically, and if the clinical situation warrants it, treatment may be started even while confirmatory diagnostic tests are pending. Both serologic and stool studies are available but have generally low sensitivity, and repeat testing is often done to increase yield. Testing for antibodies to Strongyloides is frequently performed either alone or in combination with stool testing (by polymerase chain reaction, microscopy, or even culture). Biopsy of rash or lungs in symptomatic individuals can demonstrate larvae.

Ivermectin is the first-line agent for treatment of strongyloidiasis. Duration of treatment depends on symptoms and should be at least 2 weeks for hyperinfection and dissemination. In patients with bacteremia with enteric organisms and no known source, it is reasonable to consider a hepatobiliary source. However, this patient does not have signs, symptoms, or laboratory results that indicate a high likelihood of a hepatobiliary source, and workup for that would therefore not be preferred over workup for strongyloidiasis (choice A is incorrect).

Odontogenic infections have a risk of hematogenous spread—and even endocarditis—but are usually caused by oral anaerobes. Moreover, this patient does not have any symptoms of odontogenic infection. While oral examination should be part of complete physical examination, full dental examination would not be preferred over testing for strongyloidiasis in this patient (choice B is incorrect).

Quantitative immunoglobulin levels may help diagnose conditions such as hypogammaglobulinemia and common variable immunodeficiency, but these are not more likely than strongyloidiasis in this clinical scenario (choice D is incorrect).12345

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Arthur RP, Shelley WB. Larva currens; a distinctive variant of cutaneous larva migrans due to Strongyloides stercoralis. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;78(2):186-190. PubMed ↩

-

Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Jain M, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infestation associated with septicemia due to intestinal transmural migration of bacteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(12):1331-1333. PubMed ↩

-

Krolewiecki A, Nutman TB. Strongyloidiasis: a neglected tropical disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):135-151. PubMed ↩

-

Schulte C, Krebs B, Jelinek T, et al. Diagnostic significance of blood eosinophilia in returning travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(3):407-411. PubMed ↩