tracheal inflammatory diseases

- related: Pulmonology

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

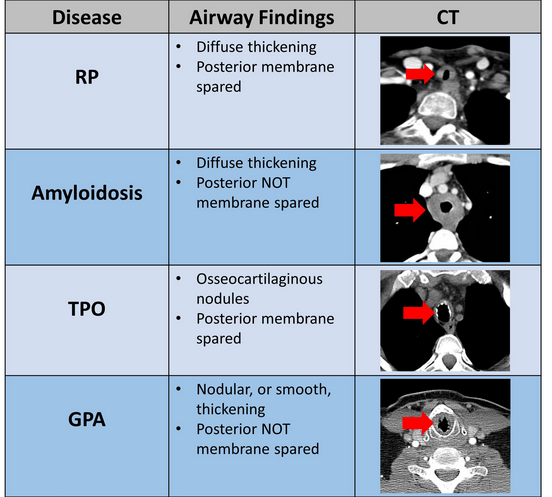

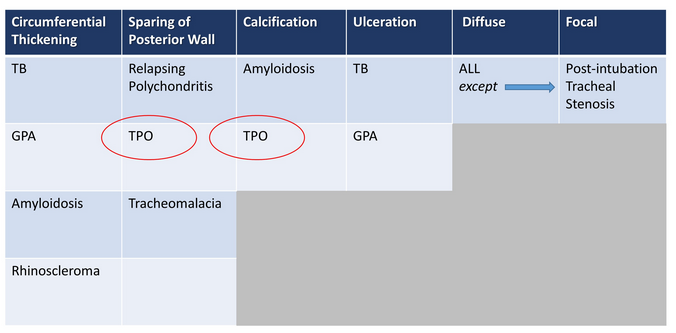

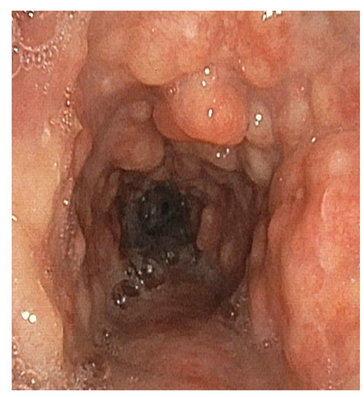

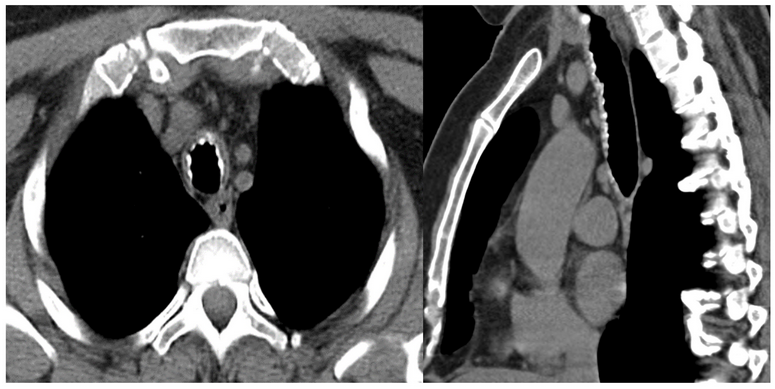

The radiographic and bronchoscopic findings presented in this case are consistent with the diagnosis of TPO, a rare yet benign tracheobronchial disease of unknown etiology (choice C is correct). The disease is characterized by multiple submucosal osteocartilaginous nodules that project into the lumen of the large airways. Nodules generally arise from the anterior and lateral aspect of the inner tracheal and proximal bronchial wall. Since these nodules arise from cartilage, the posterior membranous wall of the trachea is typically spared (Figure 4, Figure 3). Bronchoscopic findings alone are often sufficient to establish a diagnosis. Although most commonly an incidental finding, patients may present with dyspnea on exertion, wheezing, recurrent infections, and hemoptysis. In most cases, the disease progresses very slowly, although more rapid progression leading to respiratory insufficiency has been reported. Treatment is seldom required except in cases of severe airway obstruction where bronchoscopic dilation may be indicated.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a rare multisystem disease characterized by progressive inflammation and destruction of cartilaginous structures. Airway involvement in RP occurs in approximately 50% of cases. Clinical manifestations of RP with airway involvement include dyspnea, cough, wheeze, stridor, hoarseness, and aphonia. Recurrent pneumonia is the most common cause of death in these patients. Chest CT commonly shows diffuse thickening of the tracheobronchial tree, sparing the posterior membrane (Figure 4,Figure 3) (choice A is incorrect). Tracheomalacia, bronchomalacia, or tracheobronchomalacia is associated with a poor prognosis. Corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine, have been used, with varying success in the earlier phases of the disease. In advanced cases, airway interventions—such as balloon dilation, tracheobronchial stents, tracheostomy, or tracheal and laryngotracheal reconstructions—are often required.

Tracheobronchial amyloidosis typically presents in the fifth or sixth decade of life. The tissue distribution and the amount of amyloid deposition largely determine the clinical manifestations. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis is characterized by multifocal submucosal plaques of amyloid deposits distributed in a diffuse way along the airway wall. Similar to TPO, tracheobronchial amyloidosis can result in airway calcifications and airway narrowing, however, unlike TPO, the disease causes circumferential luminal thickening with no sparing of the posterior wall of the tracheobronchial tree (choice B is incorrect) (Figure 4, Figure 3). Commonly associated symptoms include progressive dyspnea, cough, hoarseness, wheezing, hemoptysis, and stridor due to airway narrowing. Systemic chemotherapy is not currently used to treat primary tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Therapeutic bronchoscopic techniques can be effective for the management of this disease, with the primary aim of repermeabilizing the airways.

The tracheobronchial tree represents the second most commonly affected area in the thorax in GPA. Patients can present with nonspecific symptoms such as dyspnea, hoarseness, and stridor. Tracheal involvement can be segmental, unifocal, or multifocal but is usually focal, involving a 2to 4-cm span of the trachea, with the subglottic portion of the trachea being most frequently affected. Tracheal wall thickening is usually circumferential and can be smooth or nodular, and the posterior membrane of the trachea is always involved (choice D is incorrect) (Figure 4, Figure 3). Although systemic manifestations of GPA are often managed with immunosuppressive therapy, most patients with subglottic stenosis due to GPA require surgical management.