value based decision making

- related: palliative care

- tags: #literature #icu

The patient is facing a major treatment decision about initiating a life-sustaining treatment that may be affected by her personal values, goals, and preferences. The recommended approach to this type of decision, known as a preference-sensitive decision, is to engage the patient (when able) or the patient’s surrogate decision maker in shared decision making. A widely endorsed definition of shared decision making is a “collaborative process that allows patients, or their surrogates, and clinicians to make health care decisions together, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, as well as the patient’s values, goals, and preferences.” The standard elements of a shared decision-making process include (1) information exchange about the relevant treatment options and the patient’s relevant values, goals, and preferences; (2) deliberation about which option is best for the patient; and (3) agreement on a decision to implement.

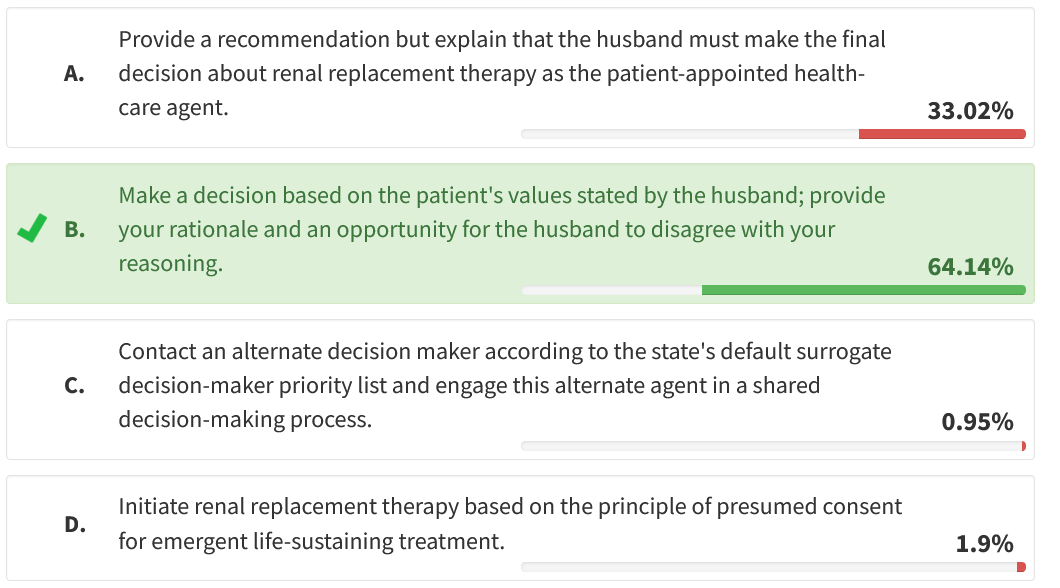

A final key component of shared decision making is to determine the level to which the patient (or surrogate) would like to participate in the decision-making process. In this case, the patient’s surrogate is expressing a desire to follow a clinician-directed decision-making model wherein the decision is deferred to the physician. According to observational studies, most patients/surrogates wish to make preference-sensitive decisions together with the treating clinician. However, some patients/surrogates prefer to be independent in the decision-making process, and approximately 5% to 20% of patients/surrogates prefer to cede decision-making control to the clinician. When a surrogate wishes to defer decision making to the physician, the physician should proceed with the standard elements of shared decision making, including a discussion of the relevant treatment options and eliciting information about the patient’s relevant values, goals, and preferences; based on this discussion, the clinician would then go on to make the decision (choice B is correct).

In clinician-directed decision making, the physician is still responsible for ensuring that the patient or surrogate understands the decision and the rationale. However, in a clinician-directed model, the physician makes the ultimate treatment decision based on his or her understanding of the patient’s values, goals, and preferences (ie, not based on the clinician’s values or other default care options) (choice D is incorrect). It is important to provide an opportunity for the surrogate or patient to disagree with the decision before proceeding with the plan of care. Pursuing a clinician-directed decision-making model is an acceptable approach to preference-sensitive decision-making, so it is not necessary nor appropriate in this case to tell the husband that he must make the decision after he has already clearly deferred the decision to the clinician (choice A is incorrect). Deferring the decision to the clinician does not imply that the surrogate is deferring their role as the surrogate decision maker (choice C is incorrect).1234

A 79-year-old woman with COPD, mild cognitive impairment, stage III chronic kidney disease, and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is admitted to the ICU with community-acquired pneumonia and septic shock. She has been supported with mechanical ventilation and vasopressors for the past 8 days and has now developed anuric renal failure.

She has designated her husband to be her health-care decision-making agent through a durable power of attorney for health care, and she has not designated any alternate agents. She has not previously expressed any specific limitations related to life-sustaining medical treatments. The ICU physician pursues a shared decision-making conversation with the husband, prompted by the consideration of initiating renal replacement therapy. The physician shares information about the current medical condition and explains the available treatment options. The physician elicits the patient’s values, goals, and preferences from the husband. The physician also elicits the husband’s preferred decision-making approach, and the husband very clearly defers this decision to the ICU physician. The husband confirms that he understands the decision at hand and states that he would like the physician to make the decision about whether to initiate renal replacement therapy.

What is the best next step for the ICU physician?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Johnson SK, Bautista CA, Hong SY, et al. An empirical study of surrogates’ preferred level of control over value-laden life support decisions in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(7):915-921. PubMed ↩

-

Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, et al; American College of Critical Care Medicine; American Thoracic Society. Shared decision making in ICUs: an American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):188-201. PubMed ↩

-

Madrigal VN, Carroll KW, Hexem KR, et al. Parental decision-making preferences in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(10):2876-2882. PubMed ↩