abdominal compartment syndrome

- related: Nephrology

- tags: #nephrology

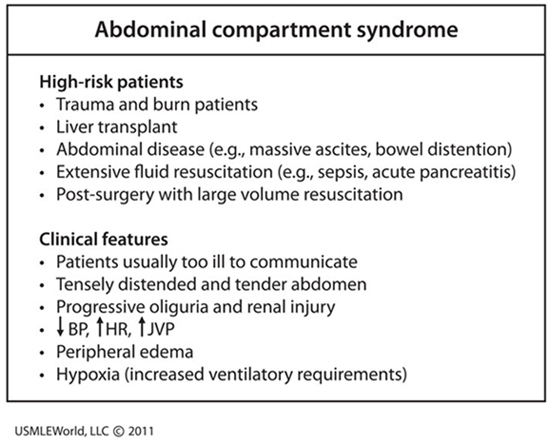

This patient’s presentation is consistent with likely intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) causing abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). Intra-abdominal hypertension is defined as pressure > 12 mm Hg; and ACS is defined as IAH with new organ dysfunction. Primary ACS is due to abdominal pelvic disease, while secondary ACS is usually due to extra-abdominal conditions (e.g., burns). Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs in patients receiving large amounts of fluids and almost any organ can be affected (especially the kidney due to its anatomical position).

While the exact pathophysiology is unknown, acute kidney injury is likely due to decreased renal blood flow and elevated renal venous pressure. A diagnosis of ACS can rapidly be confirmed by measuring hydrostatic pressure within the bladder, which is strongly correlated with intra-abdominal pressure. Lowering intra-abdominal hydrostatic pressure often quickly improves renal function; however, most patients require surgical decompression. Abdominal compartment syndrome has a mortality rate ranging as high as 40-100%.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is defined as a sustained intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) >20 mm Hg associated with at least one organ dysfunction. Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs in the setting of abdominal surgery, trauma, hemoperitoneum, retroperitoneal bleed, ascites, bowel obstruction, ileus, and pancreatitis. It can also occur from capillary leak from massive fluid resuscitation or sepsis. Increasing IAP causes hypoperfusion and ischemia of the intestines and other peritoneal and retroperitoneal structures, leading to hemodynamic, respiratory, neurologic, and kidney impairment. Renal vein compression and renal artery vasoconstriction cause oliguric AKI.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is diagnosed by measuring IAP; measurement of bladder pressure with an indwelling catheter is the standard methodology. Management includes supportive therapy, abdominal compartment decompression, and correction of positive fluid balance.

The respiratory system mechanics in this patient indicate an extremely low compliance circumstance. In this clinical context, it is likely due to an abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) complicating the patient's pancreatitis. Measuring the bladder pressure as a surrogate of the abdominal pressure will make a diagnosis, determine the severity, and guide interventions (choice B is correct).

Measuring the respiratory system mechanics during mechanical ventilation is extremely useful to elucidate causes of respiratory failure. In this patient not making active efforts to breathe, the respiratory system compliance is equal to the tidal volume divided by the inflating pressure (plateau airway pressure minus the PEEP). Since the tidal volume is relatively small, and the inflating pressure very high (44 cm H2O), the respiratory system compliance is very low. That could result from the lungs themselves being stiff, but with only moderately impaired gas exchange and absence of dense infiltrates on the chest radiograph, extremely severe lung injury with diminished compliance, as seen in ARDS, is not likely. Accordingly, the cause of low compliance here is likely the chest wall (including the abdominal compartment). When this patient's bladder pressure was measured, it was 25 mm Hg. Surgical consultation was obtained and when the bladder pressure continued to climb in the ensuing hours, the patient was taken for a decompressive laparotomy.

ACS refers to the development of abdominal hypertension that in turn leads to multiple organ failure. It is caused by many conditions encountered in the ICU, including trauma, burns, obstetric catastrophes, liver transplantation, pancreatitis, post-operative complications, and sepsis. Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) is defined as sustained pressures >12 mm Hg (16 cm H2O) with severe IAH (grade IV) indicated by pressures >25 mm Hg (34 cm H2O). A more useful measurement is the mean blood pressure minus the intra-abdominal pressure since this is a reflection of the perfusing pressure of the viscera. When this pressure falls below 60 mm Hg, the possibility of liver, gut, pancreatic, and renal hypoperfusion exists with a downward spiral of organ function and eventual death. Patients with high intra-abdominal pressures, lactic acidosis, diminished perfusing pressure of the abdominal compartment, and multiple organ failure require early identification and a rapid intervention to reduce abdominal pressure. Decompressive laparotomy is often required to halt this process.

Intra-abdominal pressure can be measured indirectly using intragastric, intracolonic, intravesical, or inferior vena cava manometry but measurement of intravesical pressure from an indwelling catheter is most widely employed. Protocols should be established in all ICUs to make this measurement readily and reliably given the wide range of conditions that may produce ACS.

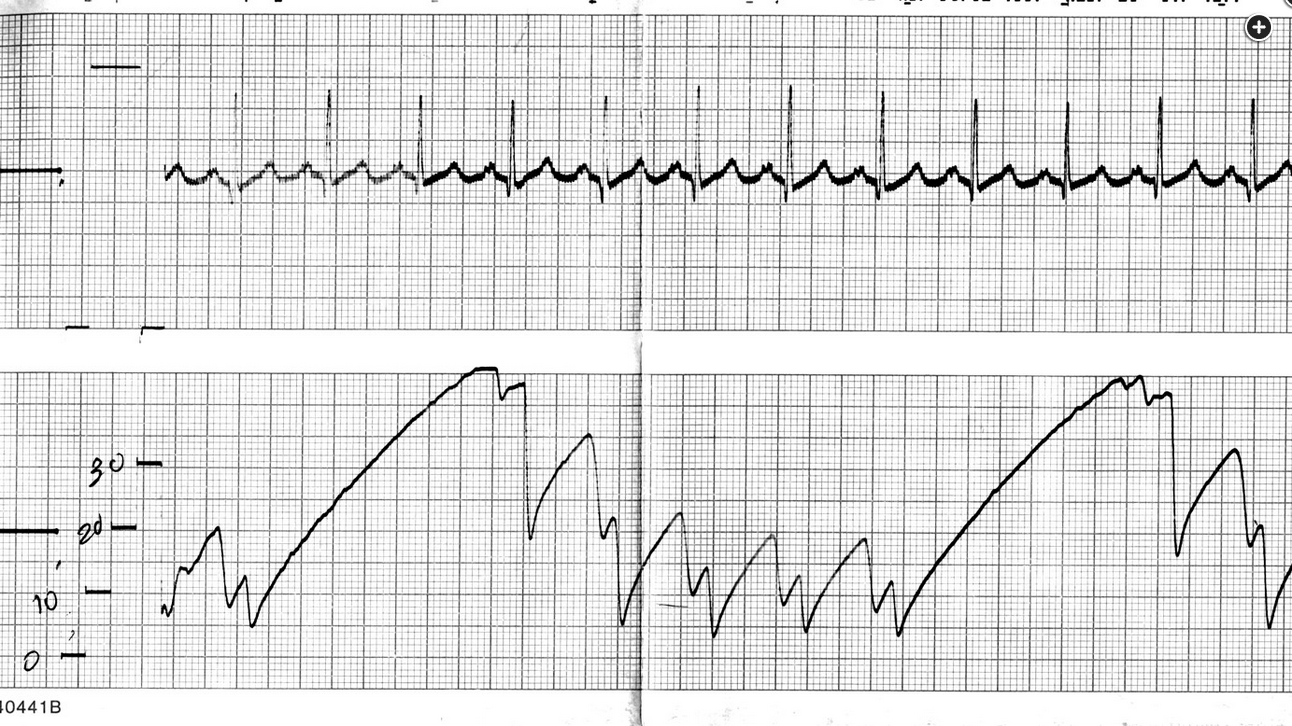

Measuring right atrial pressure would not particularly guide management of a patient with ACS (choice A is incorrect), but a suggestion of the presence of IAH is sometimes seen on a central venous pressure tracing since the intra-thoracic pressure can rise precipitously with each breath delivered by the ventilator, as shown in Figure 1. Measurement of esophageal pressure has been advocated by some to help determine the actual transpulmonary pressure in patients with confounders preventing airway pressure from accurately reflecting lung mechanics alone (eg, obesity, intra-abdominal processes) but it is more cumbersome than measurement of bladder pressure, and it would not directly assess the magnitude of IAH and the need to address it (choice C is incorrect). End tidal CO2 monitoring should be used in most patients undergoing mechanical ventilation but it would not give useful information regarding ACS (choice D is incorrect).

Right atrial pressure tracing in a patient with pancreatitis and abdominal compartment syndrome. Note the relatively high baseline pressure climbs to extremely high levels with each inspiration.