acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease

- related: Pulmonary Diseases

- tags: #literature #pulmonology #icu

The patient has SCD, an inherited single-gene autosomal recessive disorder resulting in the production of hemoglobin S, which results in RBC sickling and hemolytic anemia. Over time, numerous organs may be adversely affected, resulting in a reduced median survival and decreased average life expectancy. Pulmonary complications include asthma, restrictive lung disease, the acute chest syndrome (ACS), venous thromboembolic disease, and pulmonary hypertension. The patient presents with ACS, which is defined as a new pulmonary opacity on chest images, along with two of the following: fever, elevated respiratory rate, hypoxemia, or pleuritic chest pain. ACS is thought to result from multiple factors, including infection, in situ sickling, fat embolism, and venous thromboembolism. In an individual patient, ACS may occur owing to one or more of these processes. ACS is seen in up to 20% of patients hospitalized with SCD, frequently occurring a few days after admission for vaso-occlusive acute pain crisis, as in this patient. ACS is a serious and life-threatening complication of SCD and can result in acute respiratory failure and death.

In situ sickling can be decreased by transfusion of packed RBCs (target Hgb 10?1) or exchange transfusion, which consists of both removal of the patient’s RBCs by means of pheresis or phlebotomy and infusion of packed RBCs. Treatment with antibiotics for respiratory infection is indicated, which is one of the inciting factors for ACS, especially in children. ACS is often precipitated by infection, so empiric antimicrobial treatment for pneumonia to cover bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae along with atypical bacteria (such as Mycoplasma and Chlamydia) should also be started.

Study results have demonstrated pulmonary infection from both viral and bacterial organisms. A course of antibiotics directed against documented pathogens is typically administered in adults, especially if fever or an elevated WBC count is present; if cultures are negative, as in this case, treatment for community-acquired pneumonia is administered, which would not include tobramycin. Anticoagulation is not indicated unless testing reveals macroscopic venous thromboembolism, which was not present in this patient. Incentive spirometry may help reduce the incidence of ACS but will not result in resolution once it has occurred.2345

This patient is presenting with SCD acute chest syndrome (ACS), and simple transfusion has failed. Exchange transfusions are the best next step in treatment (choice D is correct).

ACS is defined as a new opacity at chest imaging with fever and/or respiratory symptoms in an individual with SCD. The presentation includes fever; pain in the chest, extremities, and ribs; dyspnea; and sometimes neurologic symptoms. Severe cases may result in respiratory failure and multiorgan failure and may require noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation. There is a 50% incidence of having ACS in patients with SCD. Severe ACS can be associated with mortality up to 6%.

Standard management of ACS includes adequate hydration; lactated Ringer’s solution is generally preferred over normal saline (the latter may be associated with dehydration and further sickling). Incentive spirometry is often used to reduce and mitigate the ACS episode, although without clear evidence of benefit. Pain control is usually managed with opiates, and supplemental oxygen is suggested to maintain SpO2 of 95% or more. Antibiotics should be initiated with empiric treatment for community-acquired pneumonia, usually with a third-generation cephalosporin and a macrolide. Vancomycin can be considered in severe cases. Patients with SCD are also considered to be hypercoagulable at baseline, and thromboprophylaxis is recommended in inpatients.

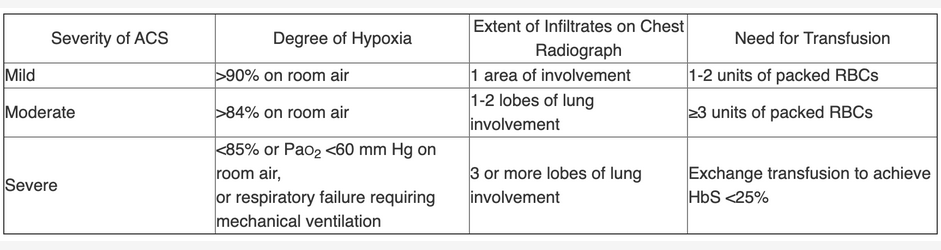

Transfusions are one of the mainstays of treatment for ACS. In severe cases with deteriorating medical conditions and/or multiorgan failure, exchange transfusions are recommended. In patients hospitalized without acute respiratory failure, simple or exchange transfusions can be administered. There are recommendations (mostly consensus based) for simple vs exchange transfusions on the basis of the hemoglobin levels and sickle cell percentages. In general, one should start with simple transfusions until the hemoglobin level is near the patient’s baseline hemoglobin level. Exchange transfusions are then indicated for ongoing crises, worsening conditions, multiorgan failure, or high percentage of sickling (>30%). Exchange transfusions are also indicated for those with criteria for severe disease, characterized by the presence of one of the following features: respiratory failure: SpO2 less than 85% breathing room air or 90% or less despite maximal supplemental oxygen; PaO2 less than 60 mm Hg or PCO2 greater than 50 mm Hg; ARDS; infiltrates in three or more lobes at chest radiography; need for simple transfusion or exchange transfusion to keep hemoglobin A at 70% or greater. This patient meets several of these indications, indicating that exchange transfusions are the best next step. In addition, because this patient’s hemoglobin level is near baseline, additional simple transfusions may result in hyperviscosity (choice C is incorrect).

Inhaled nitric oxide has been studied and has not definitely been found to be effective in ACS (choice B is incorrect). Hydroxyurea is good for maintenance and prevention of ACS but is not indicated as first-line management in an acute crisis (choice A is incorrect). Corticosteroids have also not been found to be effective although they can be of use in patients with concomitant asthma. L-glutamine has been studied with positive preventative results, but again not in the acute setting. Although pulmonary embolism is often in the differential diagnosis of ACS and has not been definitively ruled out in this case, this presentation is so characteristic of ACS that therapeutic heparin should likely not be started without additional supportive evidence of pulmonary embolism. Vaccination is also important in preventative management.

Triggers for ACS in adults include vaso-occlusive pain; fat embolism; infection with organisms such as Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, and viruses; and asthma. Almost 50% of cases have no obvious trigger. Other entities in the differential diagnosis of ACS accounting for dyspnea with or without opacities include pneumonia, severe anemia, other causes of multiorgan failure, vaso-occlusive pain, rib fracture, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure with pulmonary edema, cardiac ischemia, pulmonary embolism and/or infarction, and transfusion-related acute lung injury.678910

An 18-year-old patient with sickle cell disease (SCD) presents to an outside hospital with 2 days of fever to 39.8 °C, nonproductive cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain. The patient has a history of medication nonadherence including hydroxyurea. At admission, the patient’s hemoglobin level is 6 g/dL (60 g/L), with a baseline of 7.9 g/dL (79 g/L). The patient receives a transfusion with 2 units of packed RBCs with minimal improvement and is transferred to your hospital ICU for ongoing treatment.

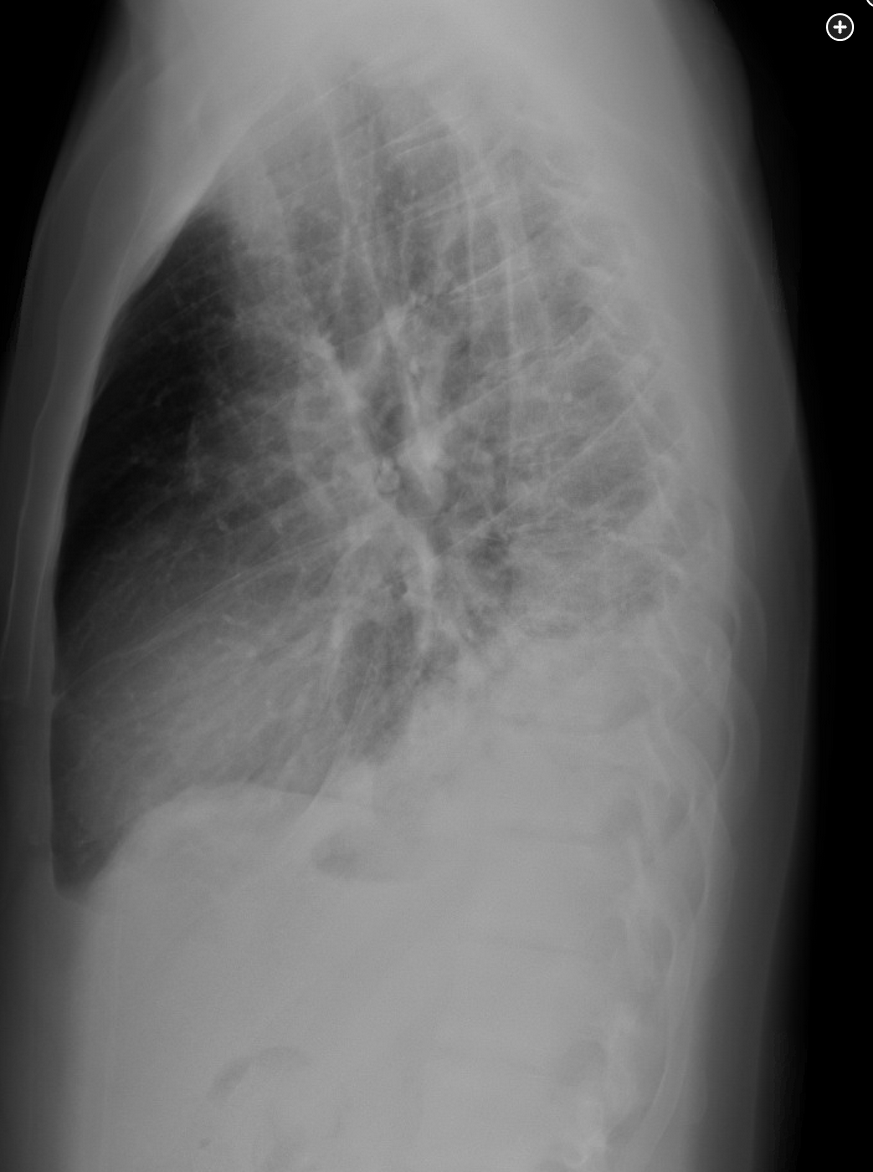

At current examination, the patient’s heart rate is 125/min, respiratory rate is 24/min with accessory muscle use, BP is 100/50 mm Hg, temperature is 39 °C, and SpO2 is 84% breathing room air and 93% with FIO2 of 0.5 breathing oxygen by face mask. Lung examination reveals coarse breath sounds with no wheezing. Laboratory test results are notable for a WBC count of 14,000/µL (14 × 109/L), hemoglobin level of 7.2 g/dL (72 g/L), and platelet count of 210 × 103/µL (210 × 109/L). Peripheral blood smear results show abundant sickled cells (≈40%). Chest radiography shows diffuse bilateral alveolar opacities. Viral polymerase chain reaction results are negative. The patient is receiving empiric antibiotics, analgesia, supplemental oxygen, IV fluids, and respiratory treatments with incentive spirometry.

In addition to the current treatment, what is the best next step for this patient?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Howard J, Hart N, Roberts-Harewood M, et al; BCSH Committee. Guideline on the management of acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2015;169(4):492-505. PubMed ↩

-

Naik RP, Streiff MB, Haywood C Jr, et al. Venous thromboembolism in adults with sickle cell disease: a serious and under-recognized complication. Am J Med. 2013;126(5):443-449. PubMed ↩

-

Novelli EM, Gladwin MT. Crises in sickle cell disease. Chest. 2016;149(4):1082-1093. PubMed ↩

-

Aboursheid T, Albaroudi O, Alahdab F. Inhaled nitric oxide for treating pain crises in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;7(7):CD011808. PubMed ↩

-

Chou ST, Alsawas M, Fasano RM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: transfusion support. Blood Adv. 2020;4(2):327-355. PubMed ↩

-

Kavanagh PL, Fasipe TA, Wun T. Sickle cell disease: a review. JAMA. 2022;328(1):57-68. PubMed ↩

-

Spring J, Munshi L. Hematology emergencies in critically ill adults: benign hematology. Chest. 2022;161(5):1285-1296. PubMed ↩

-

Ware RE, de Montalembert M, Tshilolo L, et al. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):311-323. PubMed ↩