ADEM acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is post infection autoimmune demyelination syndrome

- related: Neurology

- tags: #literature #icu

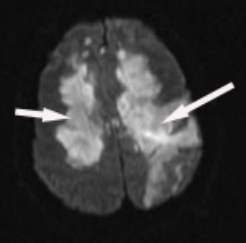

Patients with progressive obtundation can be challenging to evaluate and treat because of the breadth of disease entities that lead to nonfocal encephalopathy. In this patient, his course, the MRI findings, and findings in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) suggest the diagnosis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Specifically, ADEM is a postinfectious autoimmune encephalopathy that causes demyelination of the white matter with typical sparing of the cortical gray matter (Figure 2).

Axial diffusion-weighted MRI image. The findings show areas of patchy and confluent increased signal intensity with sparing of the cortex. There is also evidence of a subcortical hemorrhage in the left hemisphere (right side on screen) with increased signal intensity in the hemorrhage and cortical increased signal intensity, which likely represents perihematomal edema.

The arrow on the right shows the border of the white matter and gray matter. On this fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-weighted) MRI image, the bright signal intensity is evidence of demyelination. Notice how on the left side of the image (right side of the brain), the demyelination respects the border between the cortex and white matter. On the other side (right arrow), the cortex is involved, which represents edema around an area of hemorrhage, which is also a hallmark of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

The typical finding in addition to demyelination on MRI is an elevated CSF WBC count and elevated IgG index, which suggests production of IgG in the CSF in excess of blood. Intracerebral hemorrhage is seen in some patients who have extensive disease. There is a rare variant of ADEM called acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis, which manifests primarily as multifocal hemorrhage with patchy demyelination. In this patient, demyelination is the predominant finding, so ADEM is more likely than acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis. It is also notable that this patient does have cortical edema from the intracerebral hemorrhage but this MRI image does not represent cortical demyelination. The first-line treatment for ADEM is methylprednisolone.

In patients who continue to progress, plasmapheresis (not a choice), is the second-line choice. Although it is likely that IV immunoglobulins have been administered in patients with ADEM, there are few data (in case series) to support this as first-line therapy.

Acyclovir is a treatment for viral infections of the brain, specifically varicella and herpes simplex infections. Varicella and herpes infections cause cortical inflammation not demyelination.

Thiamine and folate are administered to patients with nutritional deficiencies. Thiamine deficiency leads to encephalopathy but not demyelination. Other entities in the differential diagnosis are (1) the first episode of multiple sclerosis, although this is too rapid a course; (2) aluminum toxicity from heroin smoking (“chasing the dragon”), which leads to MRI findings that can be similar but CSF findings that are not inflammatory; and (3) cuprizone toxicity, which involves a copper-binding compound that leads to rapid and complete demyelination. It is used in mouse models of multiple sclerosis, but occasional toxic exposures in humans have been described.123

A 40-year-old man presents to the ICU with progressive obtundation. According to his family, he complained of being excessively tired 3 weeks before. He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 but did not develop serious respiratory disease. He recovered from his symptoms of myalgia and fever after 5 days. Approximately 5 days before admission, he developed fever, headache, and fatigue. The next morning, he was confused and forgetful (such as leaving the shower running after he left the bathroom). He was seen by his family doctor, but his CBC count and chemistry panel were normal, and he was sent home with a diagnosis of prolonged COVID symptoms. On the morning of admission, his wife could not wake him. He was immediately seen in the ED. His physical examination on admission shows an obese man who is obtunded. His chest is clear, his heart is regular, his abdomen is obese but soft, and he has normal extremities without cyanosis. Skin changes are not seen. On neurological examination, he responds to verbal stimuli by opening his eyes but does not track with his eyes or follow commands. He has normal pupils, doll’s eyes response, and gag response. His motor examination is evaluable only with strong stimulation. On stimulation, he localizes to the stimulus on both sides and has bilateral upgoing toes on the Babinski test. He deteriorates after the first day and undergoes intubation because of the inability to protect his airway.

Evaluation for the cause of his encephalopathy includes MRI (Figure 1). He has a cerebrospinal fluid evaluation that shows a WBC count of 60,000/μL (60 × 109/L), RBC count of 5 × 106/μL (5 x 1012/L), protein level of 60 g/dL (600 g/L), glucose level of 75 mg/dL (4.16 mmol/L) (systemic glucose, 110 mg/dL [6.11 mmol/L]), elevated IgG index, and no specific oligoclonal bands. Cultures from the cerebrospinal fluid are negative after 3 days, and polymerase chain reaction tests for varicella, herpes simplex, John Cunningham virus (human polyomavirus 2), and Epstein-Barr virus show no signal. Blood evaluation shows a WBC count of 15,000/μL (15 × 109/L). Blood cultures are negative after 3 days.

What is the best next treatment?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Koelman DL, Mateen FJ. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: current controversies in diagnosis and outcome. J Neurol. 2015;262(9):2013-2024. PubMed ↩

-

Pohl D, Alper G, Van Haren K, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: updates on an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology. 2016;87(9 suppl 2):S38-245. PubMed ↩