cryptococcus pulmonary infection

- related: Pulmonary Diseases

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

- west coast

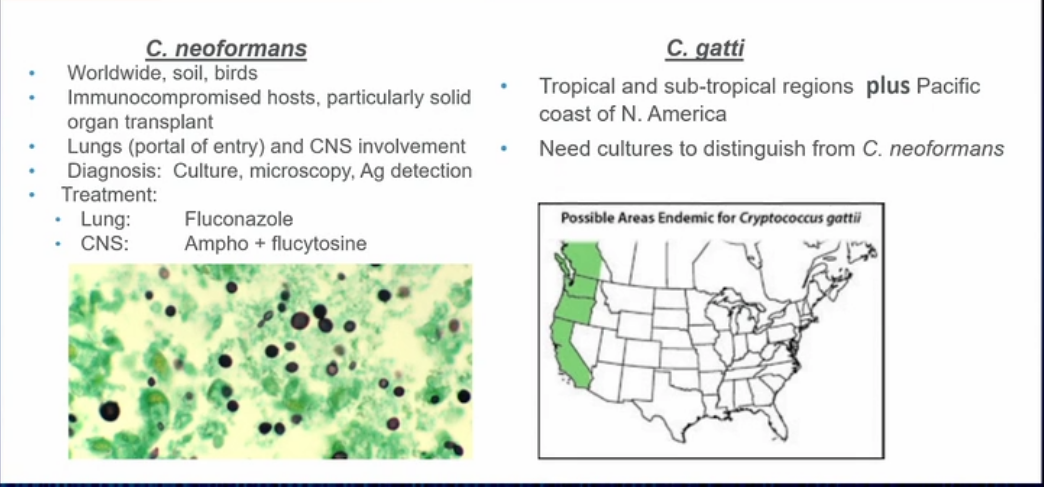

- neoformans of gatti

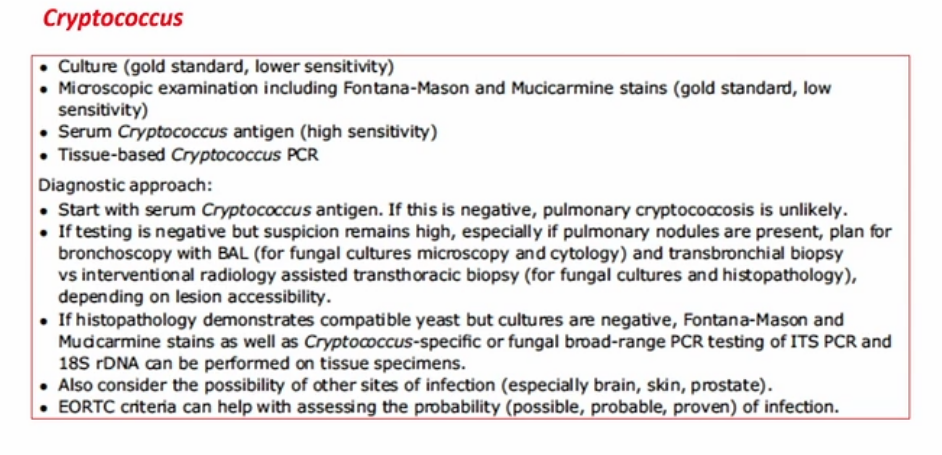

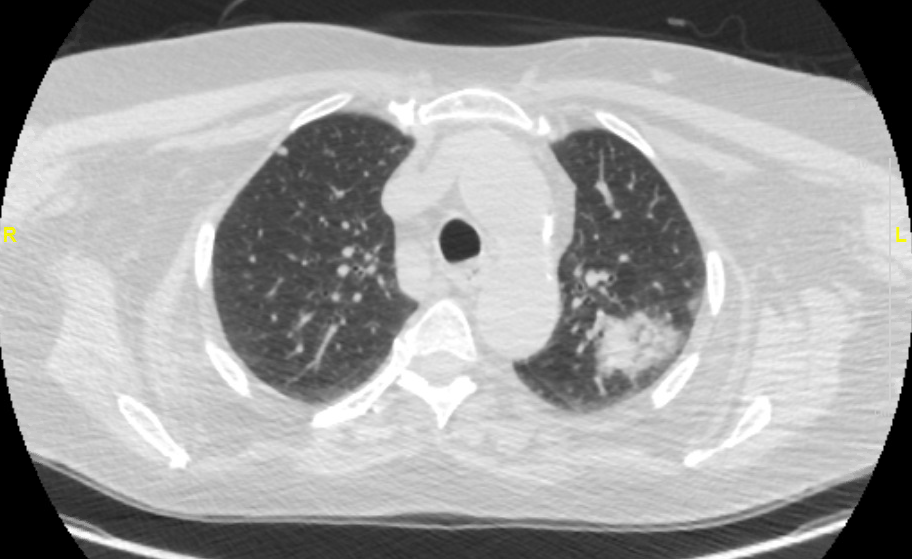

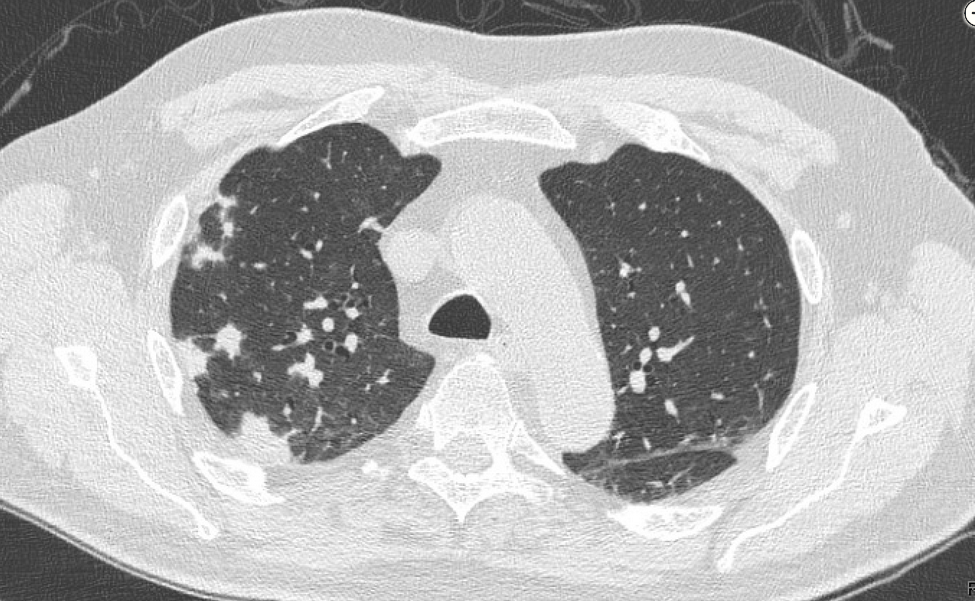

The patient was found to have pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans on a BAL fluid culture from navigational bronchoscopy, with serum cryptococcal antigen subsequently positive with a titer of 1:320. Fungal infections are well described in patients on immunosuppressive therapy as was the case in this patient. These infections may be indolent or noninflammatory in their presentation initially. The rapid radiographic progression favored an infectious process, but the patient was not ill enough (normal temperature, WBC count, and Spo2) to have bacterial staphylococcal or enterococcal pneumonia, which are not subacute illnesses. Cancer is also much less likely given the appearance on imaging and the rapid increase in the size of the lung nodules over 1 month.

- can present like mass

Numerous thoracic complications occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. These include complications of therapy such as medication pneumotoxicity or infection from immunosuppression, VTE, and multiple inflammatory processes. The epithelia of the lung and colon develop from the embryonic foregut; thus, processes that affect the GI tract may also affect the lung with lymphocytic, eosinophilic, or noncaseating granulomatous inflammation noted in many compartments of the respiratory system (airways, lung parenchyma, and pleura) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Pulmonary manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease include upper and lower airway disease with either “chronic bronchitis” or bronchiectasis-associated airflow obstruction among the more common thoracic complications. Pulmonary parenchymal processes include nodular or masslike opacities with organizing pneumonia or lymphocytic or eosinophilic inflammation noted on lung biopsy. Sarcoidlike noncaseating, granulomatous inflammation is seen as well. Inflammatory processes from inflammatory bowel disease are often corticosteroid responsive, but in patients who are on immunosuppressive therapy, infection must be excluded prior to initiating corticosteroid therapy and/or augmenting immunosuppressive therapy.

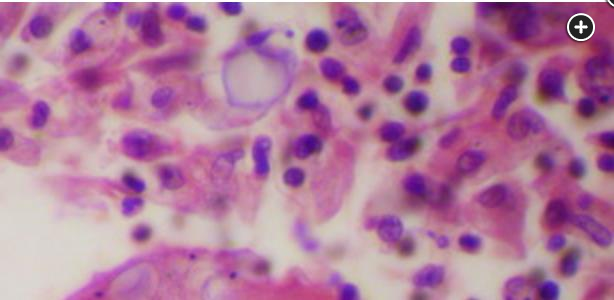

H&E lung showing Cryptococcus.

Fungal infections are a well-recognized complication of immunosuppressive therapy with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors, as well as corticosteroids, known risk factors for these infections, which are more likely to disseminate in this setting. Infection with cryptococcal organisms is most commonly seen in those with HIV infection and following organ transplantation. In healthy hosts, infection is often asymptomatic. Symptoms, when present, include fever, night sweats, malaise, weight loss, cough, sputum, chest pain, or hemoptysis. It is important to exclude CNS infection because this can be associated with elevated intracranial pressure and alters the type and length of therapy. All immunocompromised patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis should be evaluated for disseminated disease with cultures and antigen testing from blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Clinical practice guidelines recommend a prompt baseline lumbar puncture, though this should be delayed in patients with focal neurological signs or impaired mentation until after brain imaging with a CT scan or MRI. If focal neurological signs or altered mentation are present, brain imaging should be done prior to performing a lumbar puncture to assess cerebrospinal fluid pressure, cultures, and cryptococcal antigen titer. In this patient, brain MRI was unremarkable, and cerebrospinal fluid cryptococcal antigen titer was negative. Patients are treated with antifungal therapy, along with a decrease in immunosuppressive therapy, if at all possible. The colectomy in this patient will allow discontinuation of his immunosuppressive therapy and tapering of the prednisone. He was started on treatment with fluconazole with plans for 6 to 12 months of therapy.

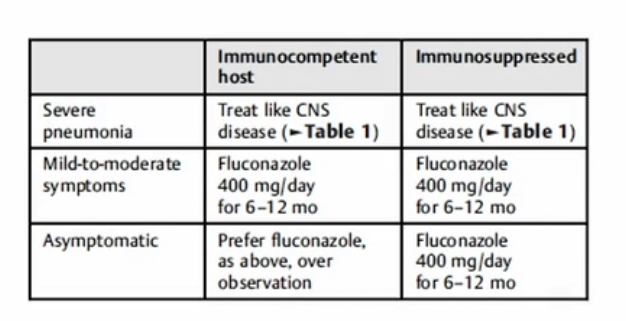

Treatment for cryptococcal pneumonia depends on whether there is infection present in other organs. If isolated to the lung, treatment is based on severity of disease. In patients with mild symptoms without diffuse infiltrates, treatment is with fluconazole for at least 6 months. For those with pulmonary disease with diffuse pulmonary infiltrates (like this patient), or if there is disseminated disease or CNS involvement, treatment is with amphotericin B in conjunction with flucytosine, followed by fluconazole, with duration tailored to the extent of disease and clinical response. Itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole are alternatives if fluconazole is contraindicated. Despite antifungal therapy, however, mortality remains high.1

This patient is immunocompromised following lung transplantation and has developed disseminated cryptococcosis, with pneumonia and meningitis. HIV negative immunocompromised patients with this type of infection generally have a poorer prognosis than HIV positive patients. The lungs are the usual portal of entry for cryptococcal infection, and a pneumonia is seen on her chest radiographs and better appreciated on her chest CT (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6).

The treatment of meningoencephalitis or disseminated disease due to Cryptococcus neoformans typically involves three distinct phases:

- An induction phase with lipid formulation amphotericin B and flucytosine. In patients with less severe disease, 2 weeks may be adequate, whereas in patients with neurologic symptoms and high (>1:512) cryptococcal antigen titers, such as this patient, induction is usually extended until 2 weeks after negative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures have been documented.

- A consolidation phase with high-dose (400-800 mg [6-12 mg/kg]) fluconazole, usually lasting 8 weeks but extended if the response to therapy has been slow.

- A maintenance phase with low-dose (200-400 mg orally daily) fluconazole, which is given for at least 1 year and is frequently extended for life in patients such as this one, who require ongoing immunosuppressive therapy. Without maintenance therapy, recurrence rates in organ transplant recipients as high as 25% have been reported, with most occurring in the 6 months following the completion of consolidation therapy.

In addition to the treatments noted above, reduction in the intensity of immunosuppression should be considered to the extent that it does not unduly risk accelerated organ rejection. Intracranial hypertension must be controlled and this is usually accomplished via daily lumbar punctures to remove CSF and produce a closing pressure of <20 cm. Percutaneous lumbar or intraventricular drains may be helpful in managing patients with an ongoing need for daily lumbar puncture beyond several days. In rare cases, ventriculoperitoneal shunting has been performed for this indication.