GPA granulomatosis with polyangitis symptoms include cavitary lung disease and neuropathy

- related: Wegener GPA granulomatosis with polyangitis

- tags: #literature #pulmonology #rheumatology

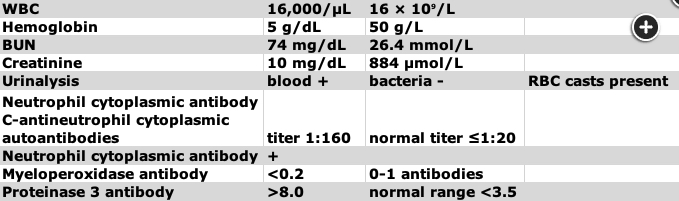

This patient has a chronic multiorgan system disease characterized by cavitary lung disease (GPA granulomatosis with polyangitis CT chest shows cavitary diseases), peripheral neuropathy, and brain and liver lesions. He has had an extensive workup for infectious and neoplastic diseases, which has been negative. The combination of chronic cavitary lung disease and peripheral neuropathy should raise the suspicion of systemic vasculitis, especially granulomatosis and polyangiitis (GPA). GPA is a necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis histology shows necrotizing granulomas) that predominantly affects small vessels of the upper respiratory tract, the lower respiratory tract, and the kidneys, although any organ can be involved.

GPA affects the upper and lower airways, kidneys, eyes, and ears. At least 50% of patients have constitutional symptoms. More than 95% of patients are ANCA positive, overwhelmingly (>90%) directed against proteinase 3 (anti-PR3 antibodies; c-ANCA).

GPA has two forms: systemic and localized. Systemic is more common, involves major organs, and is anti-PR3 positive. Localized has more granulomatous inflammation, has less vasculitis, and is less likely to be anti-PR3 positive. Patients in the localized group are more likely to be younger and female; have mainly ear, nose, and throat involvement; and be more prone to relapse.

The entire triad (upper airway disease, lower respiratory tract disease, and glomerulonephritis) may not be present initially. Upper respiratory tract symptoms include epistaxis, sinusitis, otitis media, and hoarseness. The associated granulomatous inflammation can lead to oral ulcers (as seen in this patient), nasal septal perforation, saddle nose deformity, and tracheal stenosis. Lung involvement may lead to pulmonary nodules, cavitary defects, infiltrates, or pleural effusion. Renal involvement occurs in approximately 70% of patients and is characterized by rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and weight loss are common. Ocular involvement also occurs frequently.

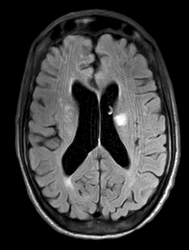

Approximately 50% of patients with GPA have neurologic symptoms, most commonly headache or mononeuritis multiplex. Approximately 10% of patients will have imaging evidence of small-vessel vasculitis in the brain or spinal cord, which may lead to ischemic strokes, hemorrhage, or white matter lesions on MRI, as were seen in our patient. Liver involvement is also common and portends a poorer prognosis, as does the absence of sinus symptoms. In contrast, the absence of renal disease is associated with better outcomes. Treatment usually consists of glucocorticoids combined with rituximab or cyclophosphamide. In the setting of rapidly progressive renal failure or severe alveolar hemorrhage, plasma exchange may be useful (GPA granulomatosis with polyangitis treatment with steroid and cyclophosphamide).

Immunoglobulin electrophoresis with IgG subclasses could be used to detect IgG subclass deficiency or IgG4-related disease. Patients with IgG subclass deficiency present most commonly with recurrent ear infections, chronic rhinosinusitis, bronchitis, bronchiectasis, meningitis, or bacterial sepsis. IgG4-related disease typically presents with lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia, salivary gland enlargement, eye disease, or kidney disease. The present clinical scenario does not suggest either of these conditions.

Semi-invasive aspergillosis in a patient with COPD could present with chronic cavitary lung disease, weight loss, and hemoptysis. A test for aspergillus galactomannan does have much higher sensitivity than a potassium hydroxide smear for this diagnosis; however, the liver and brain lesions and peripheral neuropathy seen in this patient would be atypical for a diagnosis of semi-invasive aspergillosis. Invasive aspergillosis most commonly occurs in patients who are granulocytopenic or in those who have defects in cell-mediated immunity, neither of which was present in the current case.

This patient had adequate treatment for TB 10 years ago, which reduces the likelihood of recurrence. Cavitary lung disease in active TB is associated with a high bacillary burden, so his BAL smear should have been positive for acid-fast bacilli if TB was the cause. The spot-forming unit (SFU) count of an interferon-γ release assay usually decreases with time in adequately treated patients with TB, but a persistently high SFU does not accurately predict treatment failure.12345

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Bossuyt X, Cohen Tervaert JW, Arimura Y, et al. Position paper: revised 2017 international consensus on testing of ANCAs in granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(11):683-692. PubMed ↩

-

Comarmond C, Cacoub P. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener): clinical aspects and treatment. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(11):1121-1125. PubMed ↩

-

Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis). J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98. PubMed ↩

-

Walsh M, Merkel PA, Peh CA, et al; PEXIVAS Investigators. Plasma exchange and glucocorticoids in severe ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(7):622-631. PubMed ↩