HLH associated with malignancy

- related: HLH hemaphagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- tags: #literature #hemeonc

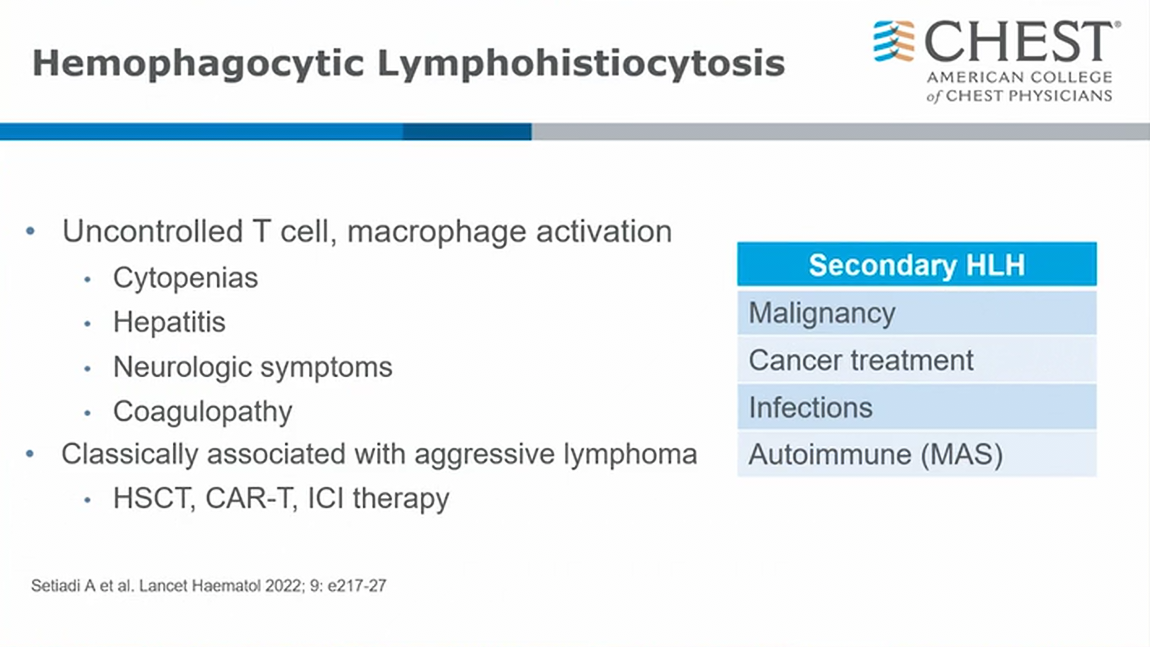

- similar to CRS

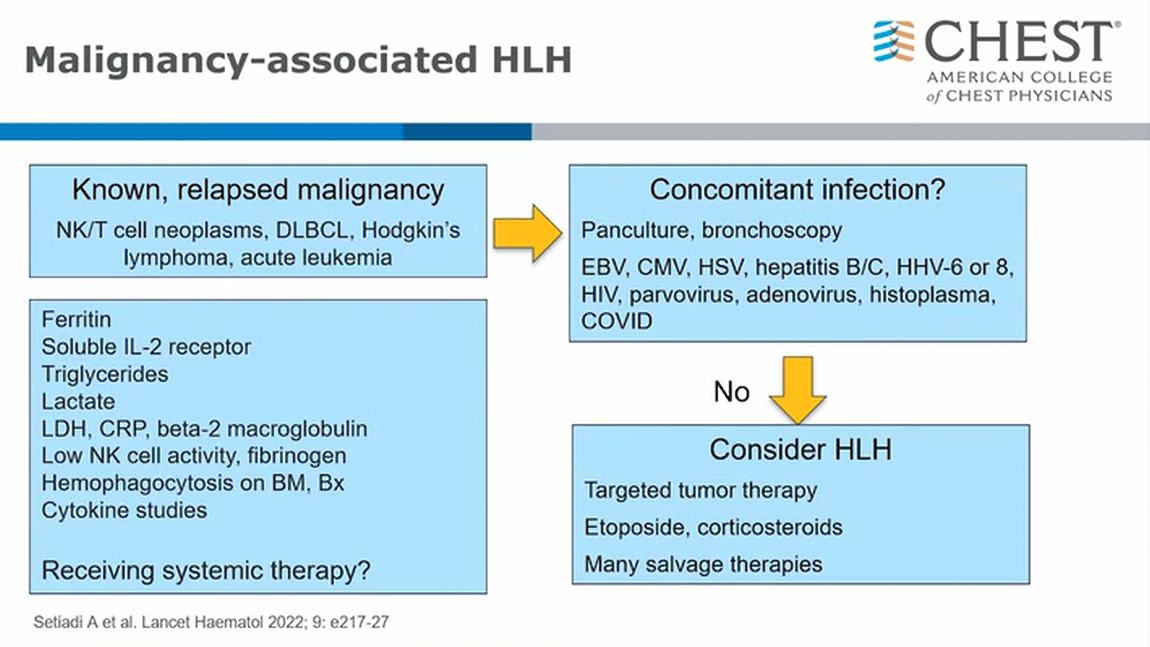

- malignancy, infection in malignancy, treatment can all cause HLH

- in cancer patients with active therapy

- HLH in autoimmune flavor (scleroderma) => call it macrophage activation syndrome

- very high ferritin (>15,000)

- elevated IL2 receptor with positive CD25 subunit

- low fibrinogen

- important to exclude active infection (2ndary HLH) prior targeted therapy (very high risk)

- etoposide +/- steroids, IL6, complement suppression etc.1

Hemophagocytic syndromes (HPSs) are rare and characterized by overstimulation of the immune system, leading to systemic inflammation and multisystem organ failure. Reported mortality ranges from 20% to 88%, with poor prognostic factors including an association with lymphoma, age >30, higher ferritin elevation, marked thrombocytopenia, male sex, and low albumin (choice C is correct; choices A, B, and D are incorrect).

Primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is generally a disorder of infancy and childhood, caused by genetic mutations that impair the cytotoxic function of natural killer and cytotoxic T cells. Secondary HPS is often associated with a predisposing condition, including malignancy (lymphoma), immunodeficiency, or infection (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]). HPS can also be referred to as macrophage activation syndrome when it occurs in association with autoimmune disease, such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, adult-onset Still’s disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

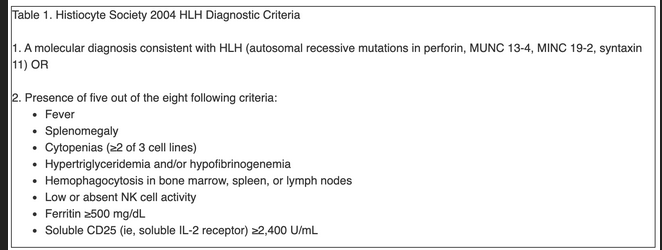

Diagnostic HLH guidelines proposed by the Histiocyte Society remain the most widely used criteria in clinical practice (Table 1), although they are poorly validated and exclude a number of described manifestations, including neurological involvement, rash, coagulopathy, hyponatremia, elevated transaminase and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and low C-reactive protein.

More recently, the H-score has been described, which provides weighting scores to the Histiocyte Society diagnostic criteria and adds elevated transaminase levels and underlying immunosuppression as additional factors, with modest improvements in predictive value when applied at the time of presentation.

Differentiation of HPSs and sepsis can be challenging, given the overlapping clinical features and even coexistence of these two clinical syndromes (look for negative sepsis workup). Molecular testing is not widely available, and the clinical significance of heterozygous mutations is unclear. Similarly, access to functional natural killer (NK) cell receptor activity and soluble CD25 testing is also limited, and the latter is elevated in many other conditions without clear evidence of HLH, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, HIV, and hypereosinophilic syndromes. Marked elevations of ferritin were once considered diagnostic of HLH but now are recognized to be nonspecific findings present in many critically ill patients (see Figure 1).

Treatment is also extrapolated from the pediatric literature and includes dexamethasone, etoposide with or without cyclosporine A, doxorubicin, IV immunoglobulin, ruxolitinib, anakinra, and allogeneic stem cell transplant. Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) and rituximab have been used in HLH associated with lymphoma and EBV, and a variety of cytotoxic agents have been employed in the setting of autoimmune disease. Plasma exchange can be considered in patients with marked elevations in ferritin and LDH, and splenectomy can be considered in relapsed cases.2345678

A 63-year-old patient is transferred from an outside facility for persistent shock despite 10 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive ICU care. Past history is significant for OSA, type II diabetes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The patient initially presented approximately 3 weeks prior to admission with malaise, fever, and loss of appetite. Diagnostic evaluation identified a normocytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver function enzymes in a mixed pattern. An extensive evaluation including liver biopsy revealed nonalchoholic steatohepatitis, and an exhaustive infectious disease evaluation was negative. The patient was admitted due to worsening mental status, hypotension, and respiratory distress and was treated for a possible aspiration pneumonia with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Over the past week, he has exhibited worsening encephalopathy, respiratory failure, and shock, requiring intubation, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressin, as well as escalating doses of norepinephrine, worsening liver failure, and progressive acute kidney injury. Antibiotics were broadened to vancomycin and cefepime, and an extensive evaluation has failed to identify an occult source of infection.

On arrival, the patient is sedated. His temperature is 39.0°C, heart rate is 122/min, BP is 90/43 mm Hg on moderate vasopressor support, and SpO2 is 94% on volume-targeted assist-control ventilation with FiO2 of 0.50 and PEEP of 10 cm H2O. Physical examination demonstrates diffuse anasarca, an irregular heart rhythm, and bibasilar crackles on lung exam. Laboratory evaluation includes a WBC count of 7,300/µL (7.3 × 109/L) with mild lymphopenia, hemoglobin of 8.9 g/dL (89 g/L), and platelet count of 46 × 103/µL (46 × 109/L). Prothrombin time is elevated at 20.6 s; fibrinogen is 121 mg/dL (3.56 g/L), and lactate dehydrogenase is 378 U/L (6.31 µkat/L). Peripheral smear demonstrates no schistocytes or evidence of hemolysis. Sodium is 130 mEq/L (130 mmol/L), BUN is 99 mg/dL (35.34 mmol/L), creatinine is 2.4 mg/dL (212.16 µmol/L), and lactate is 20.72 mg/dL (2.3 mmol/L). Liver function tests demonstrate mildly elevated transaminase levels, with a total bilirubin of 1.5 mg/dL (25.66 µmol/L) and albumin of 2.4 g/dL (24 g/L). Ferritin is 1,478 ng/mL (1,478 µg/L; normal range, 24-336 ng/mL [24-336 µg/L]), and HIV antibody testing and viral load are negative. CT scanning demonstrates patchy bibasilar infiltrates, diffuse mediastinal and paraaortic lymphadenopathy, fatty liver infiltration with mild splenomegaly, and moderate volume ascites. Cultures from blood, urine, repeat BAL, and paracentesis are negative, and echocardiogram demonstrates mild global hypokinesis without valvular abnormalities. Additional testing and a bone marrow biopsy are performed.

Considering the most likely clinical syndrome in this setting, which of the following is considered a poor prognostic factor?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Debaugnies F, Mahadeb B, Ferster A, et al. Performances of the H-score for diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adult and pediatric patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145(6):862-870. PubMed ↩

-

Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. PubMed ↩

-

Hayden A, Park S, Giustini D, et al. Hemophagocytic syndromes (HPSs) including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults: a systematic scoping review. Blood Rev. 2016;30(6):411-420. PubMed ↩

-

Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. PubMed ↩

-

Lehmberg K, Ehl S. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2013;160(3):275-287. PubMed ↩

-

Machowicz R, Janka G, Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W. Similar but not the same: differential diagnosis of HLH and sepsis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;114:1-12. PubMed ↩