local anesthetic systemic toxicity LAST

- related: ICU intensive care unit

- tags: #literature #icu

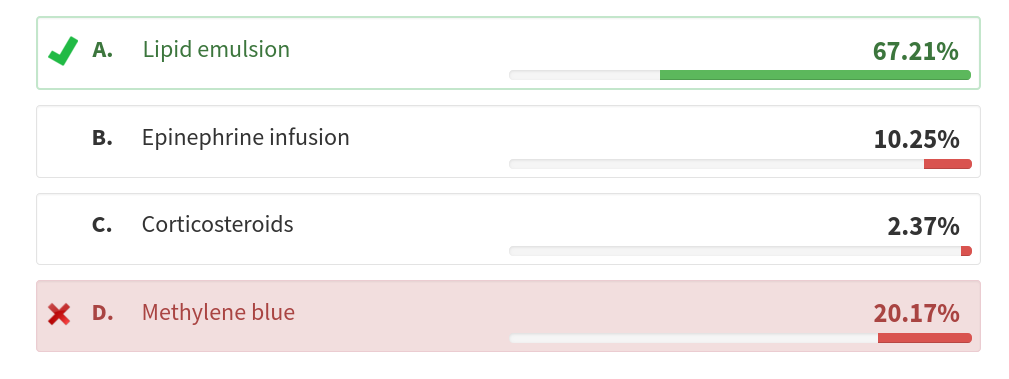

This patient has likely had a reaction to the local anesthetic (LA) agent often used for peripheral nerve blocks during joint procedures and other types of regional anesthesia and is referred to as local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST). LAST is a rare but well described complication of LA treatment, and in composite studies, from retrospective reviews of registries, the incidence is estimated at 0.27 episodes per 1,000 peripheral nerve blocks (0.03%). The outcome can be fatal. The initial treatment of choice includes lipid emulsion (LE) therapy (choice A is correct).

This patient has some of the risk factors for LAST, including advanced age and a history of renal dysfunction and diabetes. Other risk factors include young age; pregnancy; female sex; other comorbidities such as CNS, hepatic dysfunction, and cardiac disease such as ischemic heart disease and arrhythmias; and the use of anesthetic in highly vascular sites or for procedures requiring large doses. Less common risk factors include low muscle mass states or sarcopenia, genetic insufficiency such as mitochondrial disease, carnitine deficiency, and low plasma protein binding conditions. Bupivacaine also has the lowest safety margin of the commonly used agents, is the most cardiotoxic, and is the most associated with LAST and the possibility of resuscitation being more difficult in the event of LAST. Intermediate causative agents include ropivacaine and levobupivacaine, but these other agents can also account for a significant proportion of LAST events. Lidocaine is the least cardiotoxic agent but has also been associated with LAST. LAST can occur in the hospital or in the outpatient setting.

LAST is primarily due to inadvertent intravascular injection and systemic absorption of LA. Clinically, findings of LAST usually develop immediately to within 15 min after injection, although delayed LAST can occur in the setting of longer-acting administered agents and in individuals with low body mass. The primary findings in LAST include neurologic and cardiac effects. Neurologic effects are the most common and can be mild, such as oral numbness, tinnitus, or a metallic taste, and can progress to anxiety, agitation, dysarthria, mental status changes, audiovisual changes, twitching, somnolence, seizures, loss of consciousness, coma, and respiratory arrest. Seizures are one of the most common presenting features and develop in 53% to 77% of those with LAST. Cardiovascular findings can include mild or profound hypotension; hypertension; tachycardia or bradycardia; ventricular arrhythmias; asystole; and, in extreme cases, cardiac arrest. One-third of cases begin with neurologic findings and progress to cardiovascular, but about one-fifth of cases have only cardiovascular involvement.

Treatment of LAST includes stopping the injection, management of the current and impending neurologic and cardiac findings, and administration of IV 20% LE immediately. These recommendations are most clear for LAST related to bupivacaine. Advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) protocols, when needed, have a few recommended caveats for ACLS in LAST, and these include reduced epinephrine boluses to ≤1 μg/kg, avoidance of vasopressin, calcium channel blockers, and β-blockers. Amiodarone is the first-line antiarrhythmic. The recommended dose of LE for most adults is a 100-mL bolus over 2 to 3 min followed by an infusion of 200 to 250 mL over 15 to 20 min. The recommended maximal dose in most studies is 12 mL/kg of 20% LE. LE infusion can be repeated or the infusion rate increased if cardiovascular instability persists. The LE infusion should be continued for at least 10 to 15 min after hemodynamic stability has been attained, and patients should be observed for at least 2 h after a seizure and 4 to 6 h after cardiovascular instability. Refractory cases of LAST may require cardiopulmonary bypass or, in rare cases, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The mechanism of action of LE for treatment of LAST is likely related to movement of the LA agent from high blood flow organs (heart or brain) to storage organs such as muscle or liver. LE may also improve cardiac output and reverse hypotension via sodium channel-mediated cardiotonic effects. In addition, routine vasopressors and antiepileptic agents should be administered. Propofol, although a lipid-based agent, is not a substitute for LE and can worsen hypotension.

Overall, there has been a decreased incidence of LAST because of awareness and preventative measures. These include administration of lower-dose anesthetic agents, adherence to the recommended administration technique of aspiration before injection, injecting incrementally, use of ultrasonography to isolate the nerve and surrounding vessels accurately when performing peripheral nerve blocks, addition of epinephrine 1:200,000 to 1:400,000 with the LA injection to provide local vasoconstriction and to be used as a marker of intravascular administration as indicated by tachycardia and hypertension, and the avoidance of heavy sedation. In addition, there should always be a LAST rescue kit available.

Methylene blue would be indicated for the treatment of methemoglobinemia characterized by cyanosis and pulse Spo2 in the 85% range and is unlikely to occur with bupivacaine and is more often associated with topical lidocaine or benzocaine anesthesia (choice D is incorrect). Although vasopressors should be administered while awaiting the effects of the LE therapy, this is not an allergic reaction, and epinephrine as a vasopressor agent would not be the initial vasopressor of choice (choice B is incorrect). Additional epinephrine beyond what might be needed for ACLS, with the prior dosing adjustments, should not be administered because this is not a direct allergic response. Although the patient has received inhaled corticosteroids in the past, this would be an unusual presentation of acute adrenal insufficiency, and corticosteroids are incorrect. Likewise, corticosteroids might be used for anaphylaxis, but this is not that reaction (choice C is incorrect).12345678

You are called to a rapid response in the day surgery clinic to evaluate a 66-year-old man undergoing elective knee arthroplasty surgery under general anesthesia with adjunctive regional peripheral nerve blockade. The patient has a history of well-controlled mild to moderate COPD with use of a long-acting β-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist with a remote history of inhaled corticosteroid use, type 2 diabetes well controlled with metformin, and mild renal insufficiency secondary to diabetic nephropathy, and he is otherwise in good health. He is a former tobacco user. There is no history of alcohol use. He has no known allergies. The arthroscopic procedure had just started with induction and administration of bupivacaine for peripheral nerve blockade and was followed by a single tonic-clonic seizure 5 min later and subsequent hypotension partially responsive to fluid administration. On examination, BP is 80/48 mm Hg, pulse is 120/min, respirations are 24/min, and pulse Spo2 is 94% with 0.4 FiO2 via laryngeal mask airway. There is no cyanosis. There is no stridor. Lungs are clear without wheezing, and cardiac examination reveals tachycardia. Point-of-care glucose is 122 mg/dL (6.77 mmol/L).

What should be administered next?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

El-Boghdadly K, Pawa A, Chin KJ. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: current perspectives. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:35-44. PubMed ↩

-

Gitman M, Fettiplace MR, Weinberg GL, et al. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: a narrative literature review and clinical update on prevention, diagnosis, and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(3):783-795. PubMed ↩

-

Harvey M, Cave G. Lipid emulsion in local anesthetic toxicity. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(5):632-638. PubMed ↩

-

Mörwald EE, Zubizarreta N, Cozowicz C, et al. Incidence of local anesthetic systemic toxicity in orthopedic patients receiving peripheral nerve blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(4):442-445. PubMed ↩

-

Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Fettiplace MR, et al. The Third American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine practice advisory on local anesthetic systemic toxicity: executive summary 2017. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(2):113-123. PubMed ↩

-

Neal JM, Neal EJ, Weinberg GL. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine local anesthetic systemic toxicity checklist: 2020 version. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(1):81-82. PubMed ↩

-

Rubin DS, Matsumoto MM, Weinberg G, et al. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity in total joint arthroplasty: incidence and risk factors in the United States from the National Inpatient Sample 1998-2013. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(2):131-137. PubMed ↩