mucormycosis can cause pseudoaneurysm

- related: Infectious Disease ID, Pulmonary Diseases

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

The cytology from the BAL demonstrates broad, thin-walled, nonseptate hyphae with irregular branching at right angles, which is consistent with pulmonary mucormycosis (PM). Mucormycosis is an invasive fungal disease seen most commonly in patients with an underlying immunodeficiency. Patients with hematologic malignancies are at risk, particularly when they are neutropenic. In these patients, the lungs are the most frequent site of infection, with sinuses being the second most common. PM is a highly lethal invasive mycotic infection that is characterized by angioinvasion, infarction, and tissue necrosis. The CT pulmonary angiogram demonstrates a 1.9 × 1.5-cm saccular contrast-enhancing lesion in the left lower lobe posterior basal segment, medial to the left lower lobe cavitary lesion (Figure 3). This constellation of findings is consistent with the diagnosis of pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm (PAP) due to PM, which is best treated with embolization (choice A is correct).

- Axial CT pulmonary angiogram with arrow showing a 1.9 × 1.5-cm saccular contrast-enhancing lesion in the left lower lobe posterior basal segment.

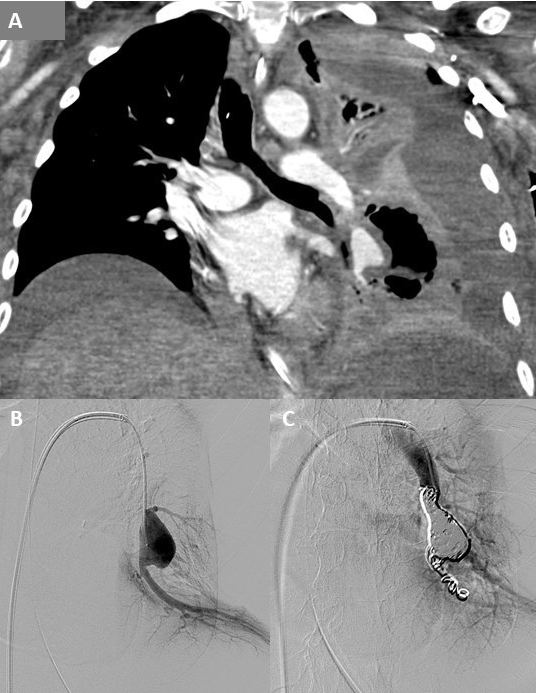

- A. Coronal CT pulmonary angiogram showing the left inferior pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm. B. Digital subtraction angiogram from a selectively catheterized left inferior pulmonary artery demonstrating the pseudoaneurysm. C. Postembolization digital subtraction angiogram demonstrating no flow to the inferior pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm.

Acquired PAP is a rare cause of hemoptysis with a wide array of etiologies. PAP can be caused by complications from pulmonary artery catheters, chest tube insertion, and biopsies, as well as penetrating thoracic trauma. Malignancies such as bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma, primary sarcoma, and metastatic sarcoma have also been reported to be associated with PAP. Chronic inflammation due to Behcet disease and Takayasu arteritis has also resulted in PAP. However, infection is the most commonly identified cause of PAP, accounting for up to 33% of cases. Infectious causes include septic emboli, TB, syphilis, pyogenic bacteria, and various fungi. Prior to the era of efficacious antibiotics, TB and syphilis were the infections most commonly associated with formation of PAP. An aneurysm arising from the pulmonary artery adjacent to or within a tuberculous cavity, also known as a Rasmussen aneurysm, is reported in 5% of patients with tubercular cavities on autopsy. More commonly seen infectious etiologies causing PAP include pyogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Klebsiella, and Actinomyces, as well and fungi such as PM and aspergillosis. PAPs arise because of inflammation of the vessel wall. The granulation tissue replaces the adventitia and media of the pulmonary arterial wall, which in turn is replaced by fibrin, leading to thinning and pseudoaneurysm formation. The destruction of the vessel wall starts in the lumen and progresses to the outer wall. Some organisms such as PM can also cause PAP by direct invasion of the vessel wall. CT pulmonary angiography is not only the gold standard to establish a diagnosis of PAP but also assists in determining candidacy for potential endovascular interventions. PAPs are frequently missed on CT studies without IV enhancement because they may appear as endobronchial lesions or lung masses.

Treatment modalities for PAP include direct coil embolization, stent placement, and embolization of the feeding vessel (Figure 4). Direct intrasaccular embolization with coils has the advantage of preserving pulmonary arteries distal to the PAP, preserving lung function, though it carries an increased risk of PAP rupture. Operative repair is rarely required for PAP. Surgical interventions are typically reserved for cases of free pleural hemorrhage, unremitting hemoptysis, and infections likely to be refractory to medical therapy (choice B is incorrect). This patient’s hemoptysis had resolved and imaging did not show free pleural hemorrhage. Furthermore, the patient’s condition was not suitable for surgical intervention, thereby making pulmonary artery embolization the best next step for the management of the PAP. Potential surgical interventions can include lobectomy, pneumonectomy, aneurysmectomy, and pulmonary artery arteriorrhaphy. Although this patient has a moderate-sized left pleural effusion, as well as a left lower lobe cavity with an air-fluid level, chest tube thoracostomy and/or CT-guided placement of a catheter in the cavity are not indicated (choices C and D are incorrect).1