pulmonary coccidioidomycosis infection

- related: Pulmonary Diseases

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

The vast majority of coccidioidomycosis infections occur in endemic zones, such as California, Arizona, Mexico, and Central America. Infections occurring outside those zones appear to be increasingly common, posing unique clinical and public health challenges. The weather plays a significant role in outbreaks of coccidioidomycosis. Spores grow during wet periods and are then disbursed during dry conditions. Climate change has resulted in drier conditions, and the absence of precipitation may cause the fungus to sporulate and aerosolize more readily. Elderly individuals, pregnant women, and members of certain ethnic groups, notably individuals of African and Filipino descent, are at risk for severe or disseminated forms of coccidioidomycosis infection. Additionally, individuals with immunodeficiency or on immunosuppression drugs, diabetics, transplant recipients, and incarcerated persons are also particularly vulnerable. The lungs are the target organ in coccidioidomycosis infection and are involved in a wide spectrum of clinical and imaging manifestations that are categorized as acute, disseminated, or chronic disease. Acute coccidioidomycosis is exceedingly common in endemic areas and is mostly self-limited.

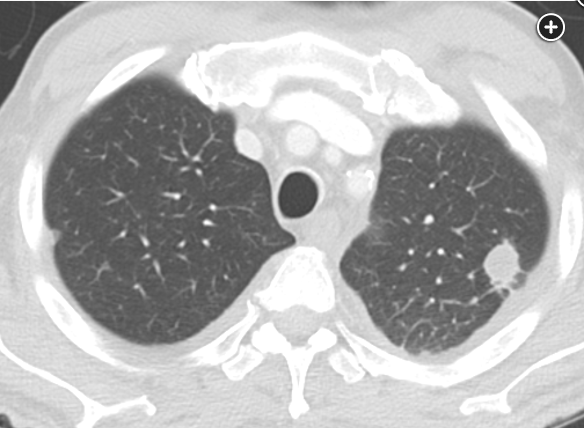

Typical symptoms include dry cough, arthralgias, and erythema nodosum. Thoracic manifestations of acute coccidioidomycosis infection include pulmonary parenchymal abnormalities, intrathoracic adenopathy, and pleural effusion. Parenchymal abnormalities occur in most symptomatic cases and consist of consolidation, nodules, cavities, and peribronchial thickening. The typical pulmonary manifestation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis infection—as seen in the above case—is miliary micronodules caused by hematogenous spread. The original focus of parenchymal consolidation may be seen, and hilar and mediastinal adenopathy are usually present.

Serologic testing is most frequently used in diagnosis and treatment monitoring of coccidioidomycosis infection. Anticoccidioidal antibodies develop in most patients, although the ability to detect them may lag behind the onset of illness by weeks or months, especially in immunocompromised hosts. Spherules are the most common morphologic form of Coccidioides seen in clinical specimens. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue specimens are often sufficient to detect spherules. PAS and GMS stains can be used to more clearly demonstrate the organisms. Identification of the fungus at culture is possible in patients presenting within 3 weeks and is most commonly performed in hospitalized patients. Serum complement fixation titer trends are often followed to guide treatment decisions.

The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis can be challenging, particularly in the case of patients who are immunocompromised. The most common approach to diagnosing coccidioidomycosis is using serologic testing to evaluate for IgM and IgG anticoccidioidal antibodies. This testing is either done by enzyme immunoassay (EIA), immunodiffusion, or complement fixation. Most recently, EIA has become the more common, initial form of serology testing. If the EIA is positive, many laboratories confirm with immunodiffusion or complement fixation. However, in patients with immune compromise, these tests have lower sensitivity. Furthermore, anticoccidial antibodies are often undetectable early in the course of disease, and this delay can be even more pronounced in the setting of immunocompromise. Thus, the negative serologic testing on admission does not rule out the diagnosis.

In patients with severe disease and immune compromise, the recommended approach for diagnosis is to use multiple diagnostic modalities, including direct visualization and culture of sputum or BAL fluid (choice A is correct). Culture and direct visualization are often the earliest ways to make a diagnosis in this scenario given the delayed or absent development of anticoccidial antibodies in patients who are immunocompromised. In this case, BAL is also an appropriate next step to evaluate for other potential bacterial, fungal, or viral pathogens as the cause of nonresolving pneumonia. In addition to serologic testing for antibodies and direct visualization and culture of sputum or BAL fluids, a third potential diagnostic modality for Coccidioides in patients who are immunocompromised is serum and urine antigen testing (not a potential answer choice). However, this antigen testing has lower sensitivity and should not be used as the sole diagnostic test for patients who are immunocompromised with severe disease.

(1-3)-β-D-glucan measurement from serum is typically used to diagnose invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients, but it is a nonspecific cell wall component of most fungal pathogens. This test can be positive in patients infected with Coccidioides as well as Aspergillus and Pneumocystis. While this test can be sent as part of the diagnostic workup, its lack of specificity makes it less important than more direct diagnostic testing for this patient with severe disease, such as BAL (choice B is incorrect).

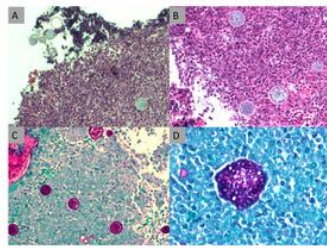

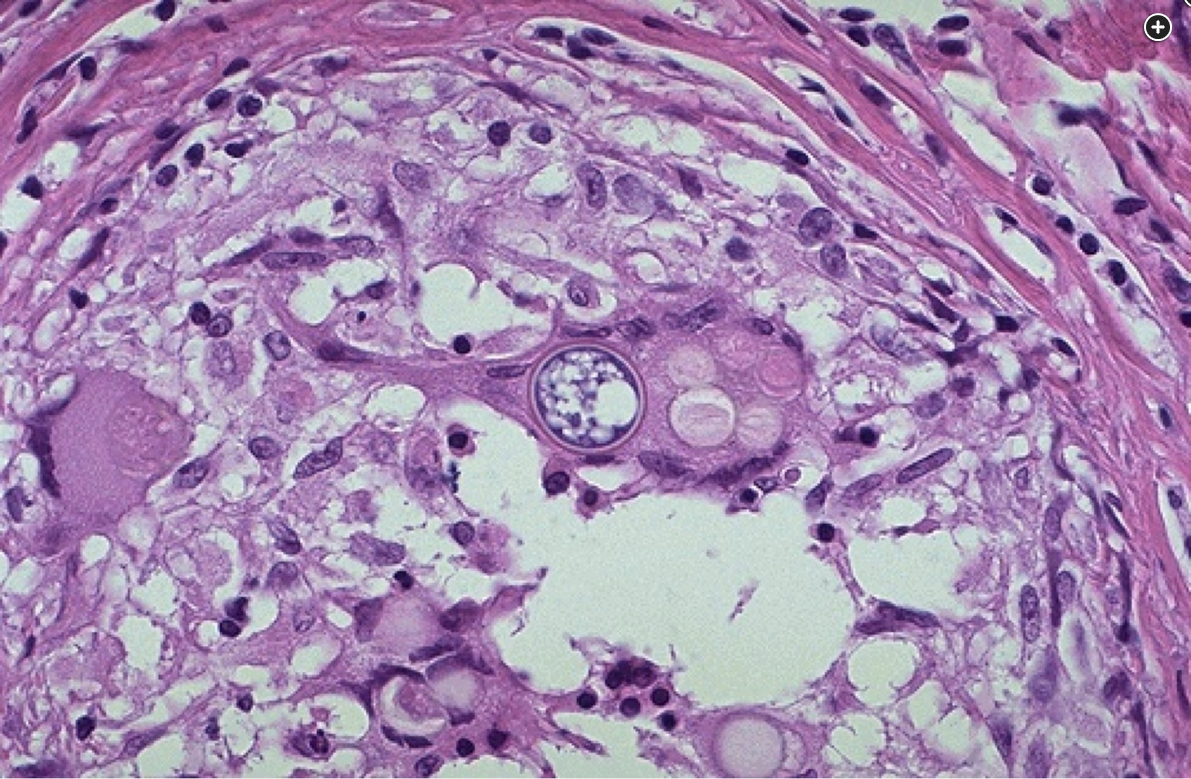

Lung histopathology shows nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation with numerous spherules containing variable-sized cysts.

The approach to treatment of primary pulmonary coccidioidal infection is determined by the severity of disease and the patient’s risk of developing severe disseminated disease. Indicators of severe disease include symptom duration >3 weeks, infiltrates involving more than half of one lung or portions of both lungs, weight loss >10% of body weight, and anticoccidioidal complement-fixing antibody concentrations of ≥1:32. Severe disease is defined by the presence of respiratory compromise. Immunologic manifestations such as erythema nodosum or rheumatologic symptoms are not representative of disseminated or severe disease.

Most patients with symptomatic coccidioidomycosis pulmonary infections should be treated with an oral azole (fluconazole and itraconazole, not voriconazole), unless the disease is severe, in which case amphotericin B can be considered in select cases. Duration of therapy often ranges from many months (6 to 12 weeks) to years and, for some patients, chronic suppressive therapy is needed to prevent relapses.

The patient described in this case has severe pulmonary coccidioidomycosis infection with findings concerning for disseminated or hematogenous disease and therefore should be treated with fluconazole. The complex clinical history, laboratory testing, and chest CT are challenging and provide for a broad differential diagnosis, including numerous opportunistic infections, including sarcoidosis and SLE-associated ILD. However, . Additionally, periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and Grocott methenamine-silver (GMS) stains were helpful in confirming the diagnosis (Figure 3).

A primary pulmonary infection is caused by inhalation of arthroconidia deep into the host airway. Once in the lung, arthroconidia can grow into a tissue form (large 70-um microspherules). Cocci will exist in the spherule stage in the host, reproducing and spreading additional spores as disease progresses. The clinical symptoms include a cough and fever. About half of those with a primary infection will have minimal to no symptoms. In patients at higher risk (diabetes, immunosuppression, Filipino and African descent), extrapulmonary symptoms include arthritis; cutaneous nodules (erythema multiforme); and, in severe cases, meningitis. Diagnosis is by culture of the organism from sputum, titer detection by complement fixation, or classic pathological findings of large spherules on biopsy. In cases of mild pulmonary disease, treatment is often not indicated. However, for those at risk (as with this patient) or with more severe disease, fluconazole 400 to 800 mg should be initiated. Itraconazole is used as an alternative, although data suggest this may be a reasonable frontline agent. Due to increased tolerability with fluconazole, this is often the initial antifungal used for nonsevere disease. For severe disseminated disease, particularly meningitis, lipid preparation amphotericin B should be used. Posaconazole and voriconazole also have activity and are reserved for itraconazole intolerance. Ketoconazole and the echinocandins are not recommended for treatment. In some cases of failure, antifungal serum drug levels may be measured to ensure drug compliance or any interference with drug metabolism.

This patient has moderate pulmonary disease with a risk for progression, so treatment is warranted. After fluconazole failure, itraconazole should be started. Both ketoconazole and micafungin do not have adequate activity for treatment (choices C and D are incorrect). Lipid preparation amphotericin is indicated for disseminated disease, which this patient does not have (choice A is incorrect).

Voriconazole has not been extensively studied for treatment of pulmonary coccidioidal infections and would not be considered first-line therapy. Amphotericin B is used in combination with fluconazole or itraconazole for patients with severe or disseminated disease, which is not the case in this patient. For patients with mild disease and without risk factors for severe disease, antifungal therapy is generally not indicated; this is also not the case with this patient. 1

The lung biopsy specimen reveals nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation with numerous spherules containing variable-sized cysts. Upper left (A) hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x10 magnification) shows nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation with spherules. Upper right (B) hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x100 magnification) numerous thick-walled spherules containing variable-sized cysts in a background of mixed population of lymphocytes. Lower left (C) PAS-stained cell block (x100 magnification) highlights the spherules. Lower right (D) PAS-stained cell block (x200 magnification) highlights the spherules with higher magnification.234

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Executive summary: 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):717-722. PubMed ↩

-

Hage CA, Carmona EM, Epelbaum O, et al. Microbiological laboratory testing in the diagnosis of fungal infections in pulmonary and critical care practice. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(5):535-550. PubMed ↩

-

Thompson GR 3rd, Bays DJ, Johnson SM, Cohen SH, Pappagianis D, Finkelman MA. Serum (1->3)-β-D-glucan measurement in coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(9):3060-3062. PubMed ↩