pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis PLG is associated with EBV

- related: Pulmonary Diseases

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

- disease: 1.pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis

- etiology: 2.lymphoproliferative disease

- association: 2.EBV

- patient: 2.40s-50s, male predominant, immunodeficient or with lymphoproliferative disorder

- sx: 2.cough, fever, dyspnea, malaise, skin nodules

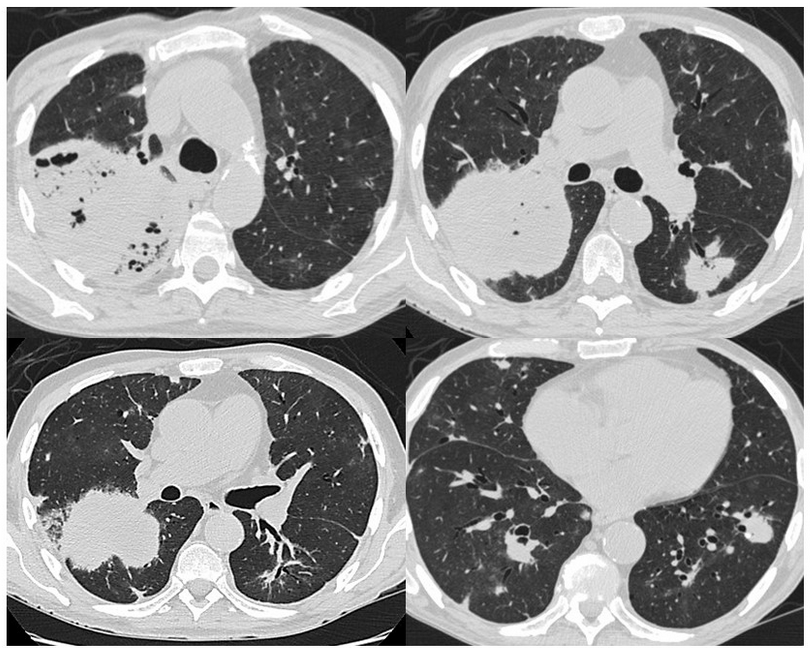

- CT: 2.cavitary mass, wax and waning

- biopsy and staining: 2.lymphocyte infiltrate, caseating granuloma, lymphocyte invasion into vessels; CD3, CD20, EBV encoded RNA

- treatment: 2.stop immune suppression if on and start immunotherapy if not

Source

This patient’s clinical, radiographic, and histolopathologic findings are consistent with the diagnosis of PLG (choice B is correct). PLG is a rare EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease characterized by multiple pulmonary nodular or masslike lesions and histopathologically defined by angiocentric and angioinvasive polymorphic lymphocytic infiltration. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG) typically manifests in the fourth and fifth decades of life with a 2:1 male predominance. It is considered a systemic disease; although lung involvement is most frequent, skin, CNS, kidney, and liver can also be involved.

Patients with an underlying immunodeficiency or those with an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder are at increased risk of developing LG. Patients with PLG most commonly present with cough, dyspnea, fevers, malaise, and weight loss. Hemoptysis usually indicates disease cavitation. Skin involvement in patients with LG includes patchy, painful, erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that typically involve the gluteal regions and extremities.

Laboratory findings in PLG are generally nonspecific and insufficient to lead to a diagnosis. The CBC count is often normal, although mild leukopenia or leukocytosis can be seen. Serologic studies routinely show evidence of previous EBV exposure without findings of acute EBV infection (EBV IgG+ and IgM−) and low-level viremia at EBV DNA polymerase chain reaction testing is frequently observed.

Chest CT features of PLG include peribronchovascular distribution of nodules, coarse irregular opacities, small thin-walled cysts, conglomerating small nodules, and cavitary masslike opacities. These lesions can wax and wane over time.

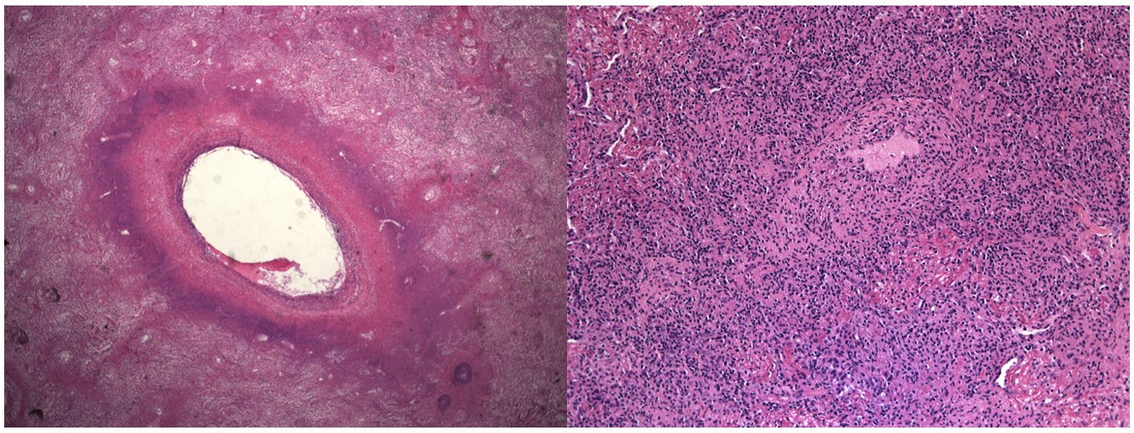

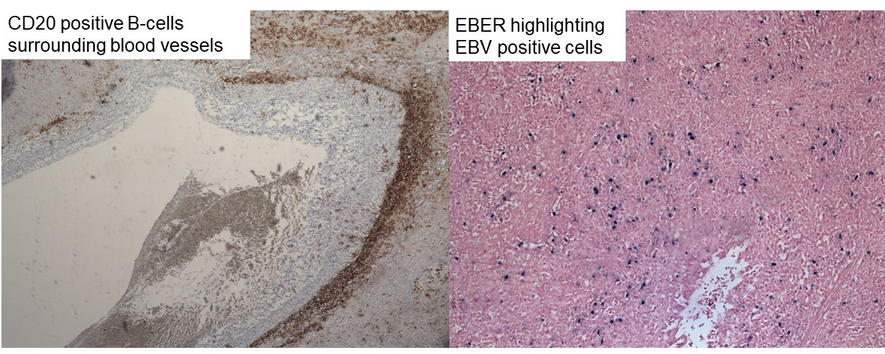

Histopathologic examination of involved tissue is essential in establishing a diagnosis of LG. When the lung is the primary site of involvement, a surgical lung biopsy is required because the presence of appropriate tissue architecture is key to establishing a diagnosis. As was the case with this patient, transbronchial lung biopsy provides an insufficient sample to assess for vascular involvement. When present, skin lesions should undergo biopsy; however, they are also commonly inadequate for establishing a definitive diagnosis. A definitive diagnosis of LG requires the presence of the following histologic triad: (1) polymorphic lymphocytic infiltrate, (2) angiitis (inflammation of blood vessels), and (3) central necrosis (granulomatosis). Although the areas of central necrosis give rise to the term “granulomatosis,” well-formed granulomas are typically absent in LG (Figure 5). LG is pathologically divided into three grades related to the proportion of EBV-positive atypical B cells relative to the reactive background of lymphocytes:

- Grade 1: Infrequent EBV-positive cells (<5/high-power field [HPF])

- Grade 2: EBV-positive large lymphoid cells or immunoblasts (5-50/HPF)

- Grade 3: Large atypical CD20+ B cells with extensive necrosis and more than 50/HPF EBV-positive cells

Accurate grading is essential to better predict disease course and guide therapy. Immunohistochemical markers used in assisting with histopathological confirmation include the following: (1) CD20, which highlights large atypical B cells; (2) EBV-encoded RNA, which highlights EBV-positive cells; and (3) CD3, which highlights angiocentric and angiodestructive T-cell infiltrates (Figure 6).

Treatment recommendations for LG are based on the grade of disease, underlying immunosuppression (if present), the presence and severity of symptoms, and the extent of extrapulmonary involvement. For those with LG associated with immunosuppressive medication, the medication should be stopped with observation recommended for those with grades 1 and 2 disease and the addition of rituximab for those with grade 3 disease. Patients with symptoms, those with extrapulmonary disease (especially neurologic involvement), and those with grade 3 disease should be referred for immunochemotherapy.

On the basis of the patient’s clinical history and radiographic presentation, limited GPA would be in the differential diagnosis, although the serologic and histolopathologic findings are inconsistent (choice A is incorrect). The upper respiratory tract is affected in almost all patients with GPA, and the lungs and kidneys are involved in 90% and 80% of patients, respectively. Patients may present with respiratory signs and symptoms, including cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea. Elevation of titers of serum c-antineutrophil antibodies against proteinase 3 in cytoplasmic granules frequently occurs in patients with GPA and can be used to assess disease activity. Lung nodules, masses, and masslike consolidation are the most common pulmonary manifestation of GPA and occur in approximately 40% to 70% of patients. They are usually multiple and bilateral and occur without a zonal predilection. Cavitation occurs in approximately 25% to 50% of nodules larger than 2 cm; the walls of the cavities may be thin or thick and nodular. The histologic hallmarks of GPA include parenchymal necrosis, vasculitis, and granulomatous inflammation. Parenchymal necrosis can take the form of neutrophilic microabscesses and/or zones of geographic necrosis (Figure 5).

The patient’s radiographic and histologic findings are inconsistent with sarcoidosis (choice C is incorrect). With that said, pulmonary macronodules and masses are seen in 15% to 25%, respectively, of patients with sarcoidosis with parenchymal involvement. They usually appear as ill-defined irregular opacities measuring 1 to 4 cm in diameter that represent coalescent interstitial granulomas. These lesions are typically multiple and bilateral and are along the perilymphatic regions such as the bronchovascular bundles (axial interstitium) or the pleural/fissural surfaces (peripheral interstitium). Occasionally, parenchymal lesions coalesce, forming conglomerate masses that consist of peribronchovascular fibrous tissue surrounding abnormal conglomerations of perihilar bronchi and vessels. These masses, which are typically seen bilaterally in the upper and middle lung zones, may mimic progressive massive fibrosis (Figure 5). The characteristic histopathologic lesion of pulmonary sarcoidosis is nonnecrotizing granulomas. Granulomas are distributed along lymphatic routes in the pleura and interlobular septa and along the bronchovascular bundles (Figure 5).

This patient’s clinical, radiographic, and histologic findings are also inconsistent with the diagnosis of COP (choice D is incorrect). Typical chest CT features of COP are extensive airspace disease in the form of patchy lower lung zone-predominant consolidation and ground-glass opacities with a subpleural and/or peribronchovascular distribution. These are usually bilateral and peripheral and are often migratory. Other less common radiographic findings include bronchial dilation, nonseptal lines or reticular opacities, and large nodules or masses. The reversed halo sign, also known as the “atoll sign,” is characterized by a central ground-glass opacity surrounded by denser airspace consolidation in the shape of a crescent or a ring and is seen in approximately 19% of organizing pneumonia cases (Figure 5). The reversed halo sign has been reported in association with a wide range of pulmonary diseases, including invasive pulmonary fungal infections, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, community-acquired pneumonia, PLG, GPA, and sarcoidosis. Although COP manifesting with cavitary lesions is unusual, it has been described in a case series and in case reports (Figure 5). COP has a histopathologic pattern characterized by patchy organizing pneumonia with intraluminal fibrosis within bronchioles and airspaces (Figure 5).1

Links to this note

-

pulmonary cavities cavitary lesions differential

- rarely, pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis can present as wax and waning cavities (pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis PLG is associated with EBV)