GBS guillain barre syndrome

- related: Neurology, toxicology and toxic ingestions

- tags: #neuro #literature #pulmonology

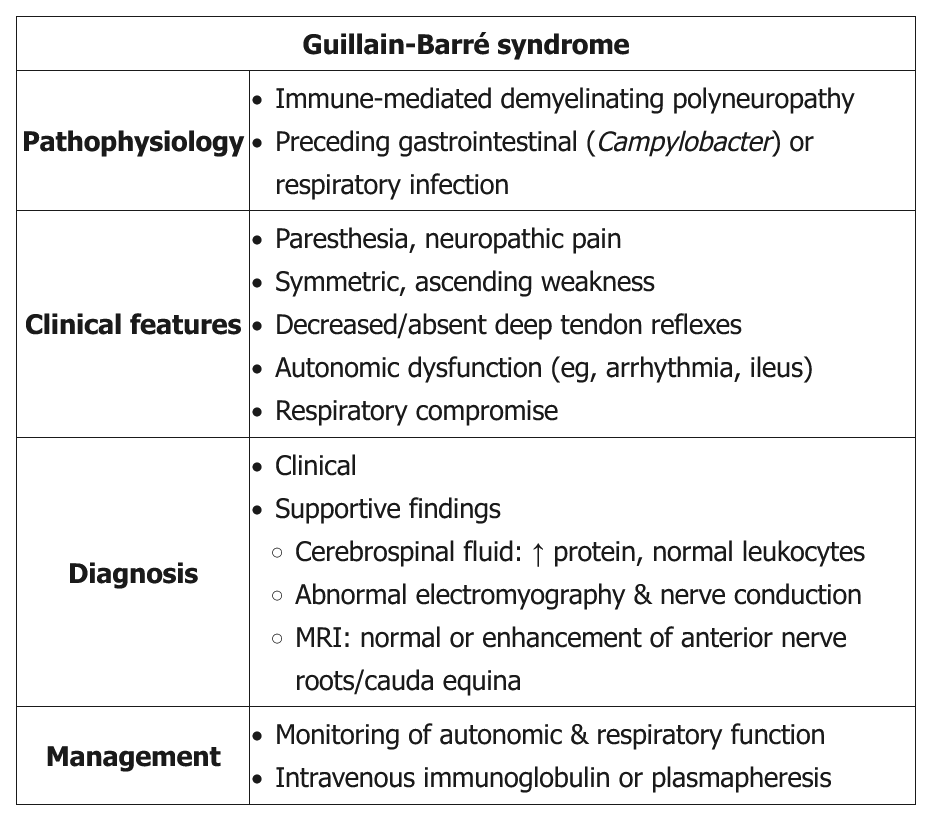

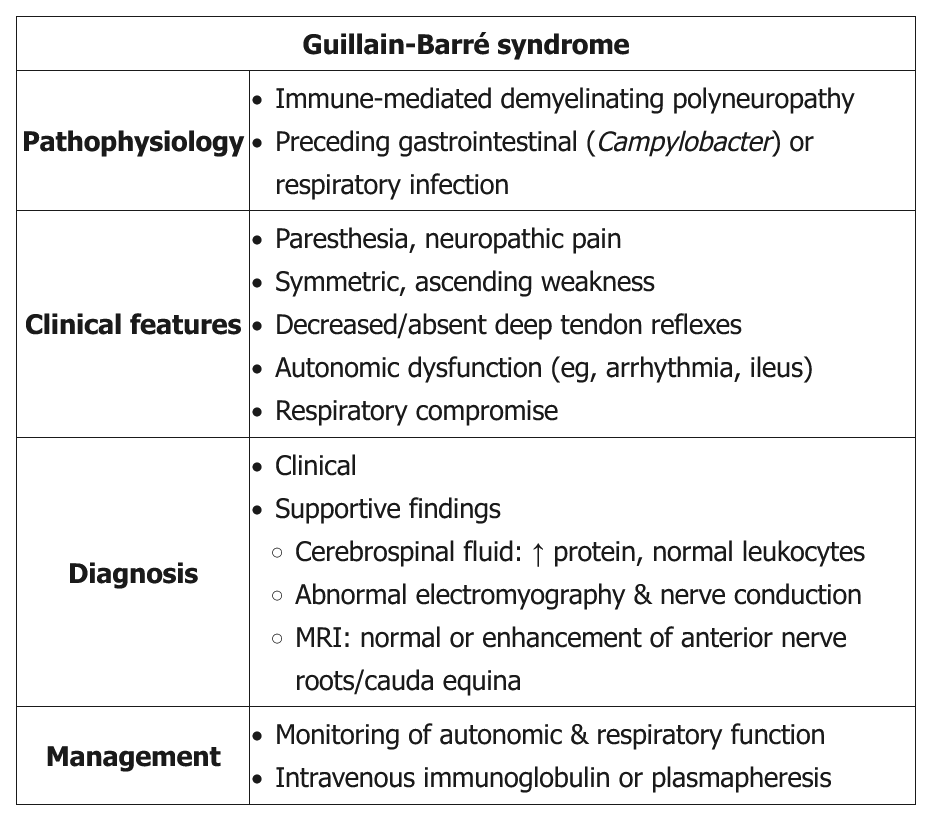

Classic GBS (AKA AIDP) presents as a progressive, symmetric ascending weakness or paralysis, often a few days to a week after a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (especially Campylobacter jejuni). About one-third of patients have no history of antecedent illness. As the weakness ascends (eg, difficulty walking with 3/5 strength in the lower extremities compared with 4/5 strength in the upper extremities in this patient), bulbar symptoms (eg, ophthalmoplegia, facial diplegia, dysarthria, dysphasia) and respiratory compromise can develop. Back pain can be a presenting feature of GBS as the disease targets primarily the proximal nerves and nerve roots in either the cervical or lumbar spine. Although GBS is primarily a motor polyneuropathy, patients can have mild sensory symptoms such as paresthesias and sensory ataxia. GBS patients also are at risk of developing dysautonomia (eg, tachycardia, diaphoresis, sluggish pupils). Examination shows absent reflexes.

Lumbar puncture is indicated in all suspected GBS patients to rule out infectious etiologies and document elevated cerebrospinal protein with a normal cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell count (albuminocytologic dissociation). However, lumbar puncture may not be diagnostic in some GBS patients as it may take up to a week after symptom onset to see the abnormal findings. Nerve conduction study and electromyography are also indicated to confirm the diagnosis and estimate prognosis.

Treatment is mainly supportive, with plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin. Current evidence does not recommend corticosteroids as they are not beneficial. Most patients recover within several weeks to months.

- high risk of respiratory failure: frequent measure vital capacity and negative inspiratory force (same for myasthenia crisis)

- plasma exchange or IVIG to combat antibodies against nerves

- Patients with GBS should receive plasma exchange or IVIG if:

- Nonambulatory

- Within 4 weeks of symptom onset

- Those who are ambulatory and recovering generally do not require treatment.

- Transverse myelitis is typically treated with high-dose glucocorticoids, not GBS

Prognosis

The manifestations of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) tend to evolve as follows:

- 2 weeks of progressive motor weakness that can lead to paralysis

- 2-4 weeks of plateaued symptoms

- Slow, spontaneous recovery over months

At a year after symptom onset, 85% of patients with GBS have regained the ability to walk and nearly 60% have had full, spontaneous neurologic recovery. Although patients with GBS typically recover without intervention, treatment with plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin shortens the time to recovery by approximately 50%.

- LP: elevated protein, normal WBC

Autonomic dysfunction as well as back pain and spasm may precede weakness in 30% of individuals experiencing Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS), a rare condition estimated at 1 to 2 cases per 100,000. Of the available options, plasmapheresis would be considered the treatment of choice for this condition (choice A is correct). Although plasma exchange may not be ideal for individuals who are hemodynamically unstable, in this case, the patient had been stabilized.

GBS can affect all age groups but more commonly affects men. The condition is thought to result from an immune response to a preceding infection that cross-reacts with peripheral nerve components because of molecular mimicry. The immune response can be directed toward the myelin or the axon of peripheral nerve, resulting in demyelinating and axonal forms of GBS. Campylobacter jejuni infection is the most commonly identified infectious agent that can precipitate GBS, with cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and Zika virus having also been associated with the condition. Some patients develop GBS after another triggering event such as immunization, surgery, trauma, medications, or bone-marrow transplantation.

Typically, symptoms progress over a few days to a week. The presence of symmetric progressive muscle weakness with loss of patellar reflexes is suggestive of the condition. Autonomic dysfunction is a well-recognized feature of GBS and is a significant source of mortality. Dysautonomia occurs in 70% of patients and manifests as symptoms that include tachycardia (the most common) and bradycardia, urinary retention, hypertension alternating with hypotension, ileus, and loss of sweating. Back pain due to nerve root inflammation can be a presenting feature and is reported during the acute phase in two-thirds of patients with GBS. Ophthalmoplegia with ataxia and areflexia may be seen in Miller-Fisher Syndrome (MFS), considered to be a more limited variant of GBS. In 25% of patients who present with MFS, some extremity weakness is noted. Of note, some patients with MFS develop fixed and dilated pupils, and antibodies against GQ1b (a ganglioside component of nerve) are present in 85 to 90% of patients with each syndrome.

Use of intravenous immunoglobulin administration could also be considered. Patients with GBS treated early with this or plasmapheresis can often experience rapid resolution of their symptoms, and it is estimated that the time to full recovery can be shortened by 40%. In this case, although the pulse rates were sporadic and dipped below 30/min, there is no indication to utilize atropine in this situation as the vital signs have already been stabilized (choice B is incorrect). Back pain due to nerve root inflammation can be a presenting feature and is reported during the acute phase in two-thirds of patients with GBS. Although corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory properties, treatment with glucocorticoids in adults with GBS is not recommended (choice C is incorrect). Thiamine, formerly known as vitamin B1, is involved in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl CoA as well as many other cellular metabolic activities, and lack of thiamine can result in peripheral neuropathies. Although TPN was being administered in this case, there is no evidence for deficiency in this vitamin and supplementing thiamine in light of the other findings would not be the best option (choice D is incorrect).1

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an autoimmune syndrome that occurs most commonly when the immune system attacks the myelin covering of the neurons of the peripheral nervous system. GBS is often preceded by a prodromal viral or Campylobacter infection. There are two variant syndromes that affect neurons directly. The axonal variant manifests with a similar progression as typical demyelinating disease, while the Miller Fisher variant is associated with early cranial nerve dysfunction and respiratory failure. The demyelinating syndrome is considered most amenable to treatment.

The typical progression of the disease includes ascending paralysis, with sensory loss that affects the most distal nerve territories first, progressing more proximately (except in the Miller Fisher variant). In the worst cases, the loss of neural signaling can lead to complete paralysis, including all of the cranial nerves. Typical treatments for GBS include IV immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis. These typically stop progression of the damage, but recovery is limited by the speed at which nerves can remyelinate or grow depending on the mechanism. In the axonal variant, the recovery can be as long as 2 to 4 years—the time it takes to regrow peripheral nerves.

Mortality in GBS is almost entirely due to medical complications associated with the severe paralysis. One complication directly related to the disease is autonomic insufficiency. In severe cases of GBS, the autonomic nerves can be damaged (particularly but not exclusively in patients with the axonal variant of GBS). The patient in this case manifests many findings of dysautonomia, including hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, and constipation. Dysautonomia can be life-threatening; in one retrospective study, the presence of dysautonomia tripled mortality. Arrhythmias, profound hypotension, and complications from critical illness, such as infections, were the most likely causes of death. Comorbid medical problems worsen the prognosis from dysautonomia (infections, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, substance withdrawal, and pulmonary emboli).

It is important to recognize that this patient has a chronic problem and is asymptomatic. Treatment of hypotension due to dysautonomia with long-acting medications such as the mineralocorticoid fludrocortisone to increase intravascular volume and the α-agonist midodrine to increase vascular tone are accepted therapies (choice D is correct). Because of the severe dysautonomia, the bradycardia reflex that is associated with alpha-agonists (through increased afterload) is usually impaired and doesn’t manifest. Although atropine would be a reasonable choice to raise the heart rate, the patient’s heart rate is 70/minute and even if lower, nerve dysfunction can be severe enough to functionally denervate the heart and atropine will not increase the rate, making this an unreliable intervention (choice A is incorrect). Additionally, some patients develop a forme fruste of autonomic denervation that leads to wild shifts in BP and heart rate as autonomic nerves intermittently respond to stimuli.

Vigilance about hypercapnia and hypoxemia from acute respiratory failure can lead caregivers to initiate therapies to improve atelectasis, such as noninvasive ventilation. Although no pulmonary parameters are given on the day her BP drops, the respiratory rate and lack of dyspnea make this unlikely (choice B is incorrect). Finally, although certain autoimmune diseases to lead to hemolytic anemias, this is not a phenomenon described in GBS (choice C is incorrect).23

Links to this note

-

- Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) is a potentially treatable autoimmune neuropathy. CIDP often presents with a progressive or relapsing symmetric proximal and distal weakness and sensory symptoms with diffuse areflexia. Its temporal course is often subacute with progression after 8 weeks of onset, which helps to differentiate CIDP from acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP aka GBS guillain barre syndrome). Atypical forms include multifocal asymmetric and distal symmetric variants, but respiratory failure is rare. CIDP may be isolated or occur in the setting of several other systemic conditions, including diabetes mellitus, lymphoma, and HIV. CSF findings are similar to those of GBS and may show albuminocytologic dissociation, and a demyelinating pattern on EMG is the key to diagnosis. Nerve biopsy is often unnecessary but, in complex presentations, can differentiate CIDP from vasculitis or amyloidosis. First-line treatments include glucocorticoids, periodic IVIG, or plasma exchange, which all have similar efficacy. Treatment is typically continued for at least 6 months. Half of patients achieve remission, but the other half relapse and require resumption of immunotherapy. Second-line therapies, including azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, or cyclophosphamide, are often used off-label to treat refractory disease.

Footnotes

-

Chakraborty T, Kramer CL, Wijdicks EFM, et al. Dysautonomia in Guillain-Barré syndrome: prevalence, clinical spectrum, and outcomes. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32(1):113-120. PubMed ↩

-

Zaeem Z, Siddiqi ZA, Zochodne DW. Autonomic involvement in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an update. Clin Auton Res. 2019;29(3):289-299. PubMed ↩