myasthenia crisis

- related: Neurology, GBS, myasthenia gravis

- tags: #neuro #literature #pulmonology #icu

- bulbar symptoms (dysphagia, vision problems, shortness of breath)

- normal respiratory mechanics if intubated for hypercapnic respiratory failure

- recent antibiotics, infection, surgery

- macrolides, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, magnesium, and β-blockers.

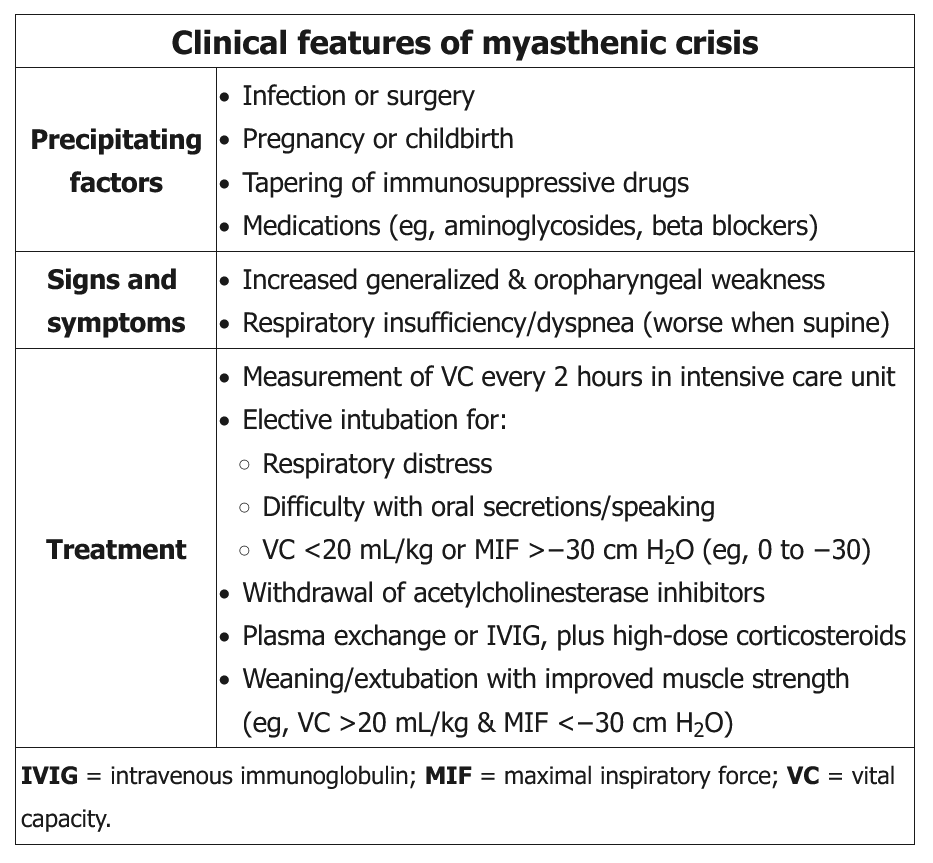

Myasthenia gravis can be a debilitating and potentially life-threatening autoimmune disorder characterized by fluctuating weakness of ocular, bulbar, respiratory, and extremity muscles. The mechanism involves autoantibodies targeting the postsynaptic muscle membrane, including nicotinic acetylcholine and muscle-specific tyrosine kinase receptors, with complement-mediated damage to the postjunctional membrane. While many myasthenia crises can be spontaneous, other precipitating events include infections; injury; a dose reduction of immunosuppressant therapy; or the addition of medications known to unmask or worsen myasthenia, including macrolides, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, magnesium, and β-blockers. The recent addition of ciprofloxacin could be contributing to her acute crisis, and discontinuation is warranted. Significant crises warrant close monitoring of respiratory function, including symptoms, secretion clearance, and vital capacity that falls below 30 mL/kg ideal body weight.

Monitoring respiratory mechanics is helpful in determining which patients should be considered for close observation in ICUs and possible intubation. Vital capacity that trends lower than 15 to 20 mL/kg body weight may be the best single metric. Maximum inspiratory pressure greater than (ie, less negative) −30 cm H2O is a better predictor than FEV1 or peak flow. However, decisions to intubate should not be based on pulmonary function test changes alone because these thresholds demonstrate risk of respiratory failure, not necessarily benefits of intubation. This patient’s pulmonary function tests are reduced from baseline but not to the threshold that would suggest ICU admission, need for noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, or early intubation.

Both IV immunoglobulin (IVIG; 2 g/kg in evenly divided doses over 2-5 days) and plasma exchange (five exchange treatments of 3-5 L with 5% albumin over 1-2 weeks) have been shown to be effective in life-threatening crises, but neither has been clearly shown to be superior to the other. While therapeutic plasma exchange may have a more rapid onset than IVIG, it may also have more complications. While consensus guidelines from experts may lean toward plasma exchange, several case series have shown conflicting outcomes. The dosing of IVIG and the number of therapeutic plasma exchanges are both inadequate in the response.

Many experts suggest holding the anticholinesterase medications for patients with fulminant respiratory failure to keep their cholinergic features of increased salivation and respiratory secretions to a minimum. Increasing the dose of pyridostigmine above her baseline dose at this time may exacerbate her respiratory failure.

Active monitoring of respiratory muscle strength (measurement of vital capacity [VC] and maximal inspiratory pressure [MIP] or negative inspiratory force) is recommended. Early intervention with noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation can be lifesaving. Elective intubation should be considered if there is decline in VC to less than 20 mL/kg of ideal body weight, if MIP is less negative than −30 cm H2O, if there is progressive hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis, or if there is difficulty handling oral secretions. In addition to monitoring and support of respiratory function, potential triggers should be addressed as possible (such as treatment of infections and discontinuation of medications that are new or known to be associated with myasthenic crises).

Anticholinesterase inhibitors should be stopped temporarily while the patient is on mechanical ventilation to minimize secretions. Weaning and extubation are considered in patients with improved muscle strength (eg, ability to lift head off bed, VC >20 mL/kg, MIF <-30 cm H2O).

Several treatments target the underlying autoimmune disorder. The most rapidly acting of these therapies and the mainstays of treatment are plasma exchange and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG). Neither is definitively superior to the other, but plasma exchange may have a more rapid onset than IVIG, acting within 1 day, and is the fastest acting of all immunotherapies recommended for the management of myasthenic crises. Of note, plasma exchange should not be performed after IVIG is administered because it will result in removal of the immunoglobulin along with the patient’s plasma. Plasma exchange is a form of therapeutic apheresis or plasmapheresis in which the patient’s plasma is removed and replaced with fresh plasma. Other forms of therapeutic apheresis use different types of replacement fluid such as colloids or crystalloids.

Corticosteroids have a much slower onset of action of about 2 to 3 weeks but can be continued to provide benefits that last beyond the more rapid, but shorter lasting, effect of plasma exchange or IVIG. Corticosteroids can be associated with an initial worsening of symptoms that usually occurs about 1 week after their initiation or increase in dose but that is mitigated by the early improvement offered by plasma exchange or IVIG.

Thymectomy is considered in select patients with MG, either for treatment of thymoma or in young patients with antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor even in the absence of thymoma. The benefit of thymectomy occurs over years (choice C is incorrect).

Ravulizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that can be used as a corticosteroid-sparing agent in the long-term management of MG. It blocks the membrane attack complex by binding to C5, thereby preventing destruction of the postsynaptic membrane. It has onset in 1 to 2 weeks, with a long-lasting effect, and can be dosed at 8-week intervals (choice D is incorrect).123

- myasthenia crisis, IVIG

Links to this note

-

- high risk of respiratory failure: frequent measure vital capacity and negative inspiratory force (same for myasthenia crisis)

Footnotes

-

Neumann B, Angstwurm K, Mergenthaler P, et al; German Myasthenic Crisis Study Group. Myasthenic crisis demanding mechanical ventilation: a multicenter analysis of 250 cases. Neurology. 2020;94(3):e299-e313. PubMed ↩

-

Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87(4):419-425. PubMed ↩