idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis IPH is idiopathic DAH

- related: Pulmonology

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

- disease: 1.idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis

- sx: 2.recurrent hemoptysis, DAH with negative workup

- association: 2.may be associated with celiac disease

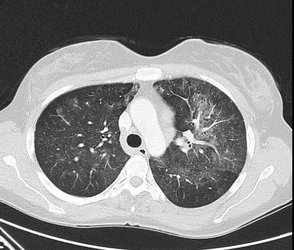

This patient is presenting with recurrent hemoptysis, anemia, bilateral opacities at imaging, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage on the basis of BAL results, and a biopsy result showing bland hemorrhage (no vasculitis) consistent with a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (IPH). IPH is a rare cause of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). IPH is more common in children (80% of cases, with an incidence of 0.24-1.23 cases per million) than in adults but is well described in adulthood as well. IPH manifests with the classic triad of recurrent, intermittent hemoptysis (often with DAH); microcytic anemia; and alveolar opacities at imaging without a clear cause, as in this case. Hemoptysis is the presenting symptom in approximately 80% of patients. Other findings include dyspnea, dry cough, chest pain, fever, fatigue, and clubbing. Pulmonary function tests, if performed during an acute event, may show an elevated diffusing capacity due to blood in the alveoli. Imaging shows diffuse alveolar infiltrates as in this case.

IPH is generally idiopathic and limited to the lungs, although both autoimmune and genetic causes have been postulated. Associated findings may include celiac disease (known as the Lane-Hamilton syndrome), and this may be present in up to 28% of patients in the pediatric population. Avoidance of gluten in those with this syndrome has been associated with significant improvement of pulmonary symptoms in some series. IgA deficiency may also be present. Testing for IgG and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibody is based on suspected coexisting celiac disease.

Bronchoscopic evaluation is generally performed to identify DAH (Figure 4) and to rule out infection. The definitive diagnosis of IPH, particularly in adults, usually requires histopathologic analysis and, when performed, shows intraalveolar hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia, and thickening of the intraalveolar septa because of hemosiderin. This is bland hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis, capillaritis, immune complex deposition, or neutrophilic infiltration of the alveolar septa that is seen with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAVs), connective tissue, and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibody disease. Interstitial collagen deposition can be seen in patients with chronic IPH.

Severe cases of IPH that can manifest with hemoptysis, hypoxemia, and respiratory failure are usually treated with systemic corticosteroids alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive regimens, and, although the data are not robust, corticosteroid use may result in improved survival. Patients with IPH usually die from acute respiratory failure in the setting of acute hemorrhage or chronic respiratory failure due to pulmonary fibrosis. In the pediatric population, the 5-year survival has increased to between 67% and 84%. In adult cases, 14% of patients die during the acute disease, but survival beyond 40 years of age has been documented. IPH can progress to pulmonary fibrosis and end-stage lung disease likely owing to excessive iron deposition.

IPH is a diagnosis of exclusion made by excluding infection, Goodpasture syndrome, AAV, and other rheumatologic and autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus. In addition, potential drug or toxin exposure and other causes of bland pulmonary hemorrhage (anticoagulants, antiplatelets, thrombolytics, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and cardiac valvular abnormalities) must be excluded. A rare cause of hemoptysis, such as catamenial hemoptysis, must also be excluded. This patient does not have other signs of systemic disease, such as renal or sinus disease, and ANCA and anti-GBM test results are negative, making a systemic vasculitic disease less likely. In addition there is no vasculitis reported at biopsy. Although this patient has a history of asthma, there is no clear evidence of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis according to the laboratory test results (an absence of eosinophilia and negative ANCA findings) and no extra pulmonic findings such as mononeuritis multiplex or renal disease. Structural airway abnormalities, including cancer, and arteriovenous malformation must also be excluded.

Cocaine use is also associated with hemoptysis but is usually temporally related to acute inhalational use of cocaine. Although this patient has a remote history of cocaine use, results of her current toxicology screen are negative. Another rare cause of hemoptysis include catamenial hemoptysis due to thoracic and parenchymal endometriosis, but in these cases the hemoptysis is temporally associated with active menstruation.12345

An 18-year-old woman is seen in the ED for hemoptysis and dyspnea. The patient describes coughing up approximately 4 tbsp (60 mL) of bright red blood 2 h previously. The episode was unrelated to any activity. She reports no fever, chills, upper respiratory tract symptoms, or pleuritic chest pain. She has had six to eight similar episodes in the past 4 years. One required hospitalization for associated dyspnea and hypoxemia. A lung biopsy was recommended at that time, but she and her parents declined. Her medical history is remarkable for asthma well controlled with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid, montelukast, and an albuterol inhaler as needed. She is receiving no other medications. She is a first-year college student. She is sexually active, and her last menstrual period was 2 weeks previously. She reports no tobacco use or vaping but has used cocaine in the past but not currently. She has no GI complaints and reports that her nutritional status is good.

On examination, she is in mild respiratory distress. Her Spo2 with 2 L O2 via nasal cannula is 89%. Her respiratory rate is 20/min, pulse is 98/min, and BP is 110/60 mm Hg. She is afebrile. Her lungs have a few scattered crackles without wheezing. Her laboratory test results are notable for a hemoglobin concentration of 9 g/dL (90 g/L), mean corpuscular volume of 76 µm3 (76 fL), and WBC count of 8,000/µL (8 × 109/L) with a normal differential count. Platelet counts and coagulation study results are normal. Her serum creatinine level is normal. Urinalysis results are within normal limits without RBCs or casts. Results of her toxicology screen are negative. Imaging is shown in Figures 1 through 3. Results of autoimmune laboratory tests, including antinuclear antibody, p-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and c-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, are negative. The result of an antibasement membrane antibody screen is negative. Transthoracic echocardiogram results are unremarkable. She undergoes bronchoscopy with BAL (Figure 4) and subsequent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery biopsy. The pathology report describes hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the alveoli and intraalveolar septa without vasculitis.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Links to this note

Footnotes

-

LaFreniere K, Gupta V. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. PubMed ↩

-

Saha BK, Bonnier A, Saha S, et al. Adult patients with idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: a comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(6):1627-1640. PubMed ↩

-

Saha BK, Milman NT. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: a review of the treatments used during the past 30 years and future directions. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(7):2547-2557. PubMed ↩

-

Saha BK. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis: a state of the art review. Respir Med. 2021;176:106234. PubMed ↩