massive transfusion protocol

- related: transfusion medicine, Hematology

- tags: #hemeonc #literature

- Ratio 1:1:1:1: pRBC, FFP, plt, cryo

- hypocalcemia is common abnormality after massive transfusion

This patient has massive transfusion requirements, for which a 1:1:1 ratio of transfusion of PRBCs, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets is recommended.

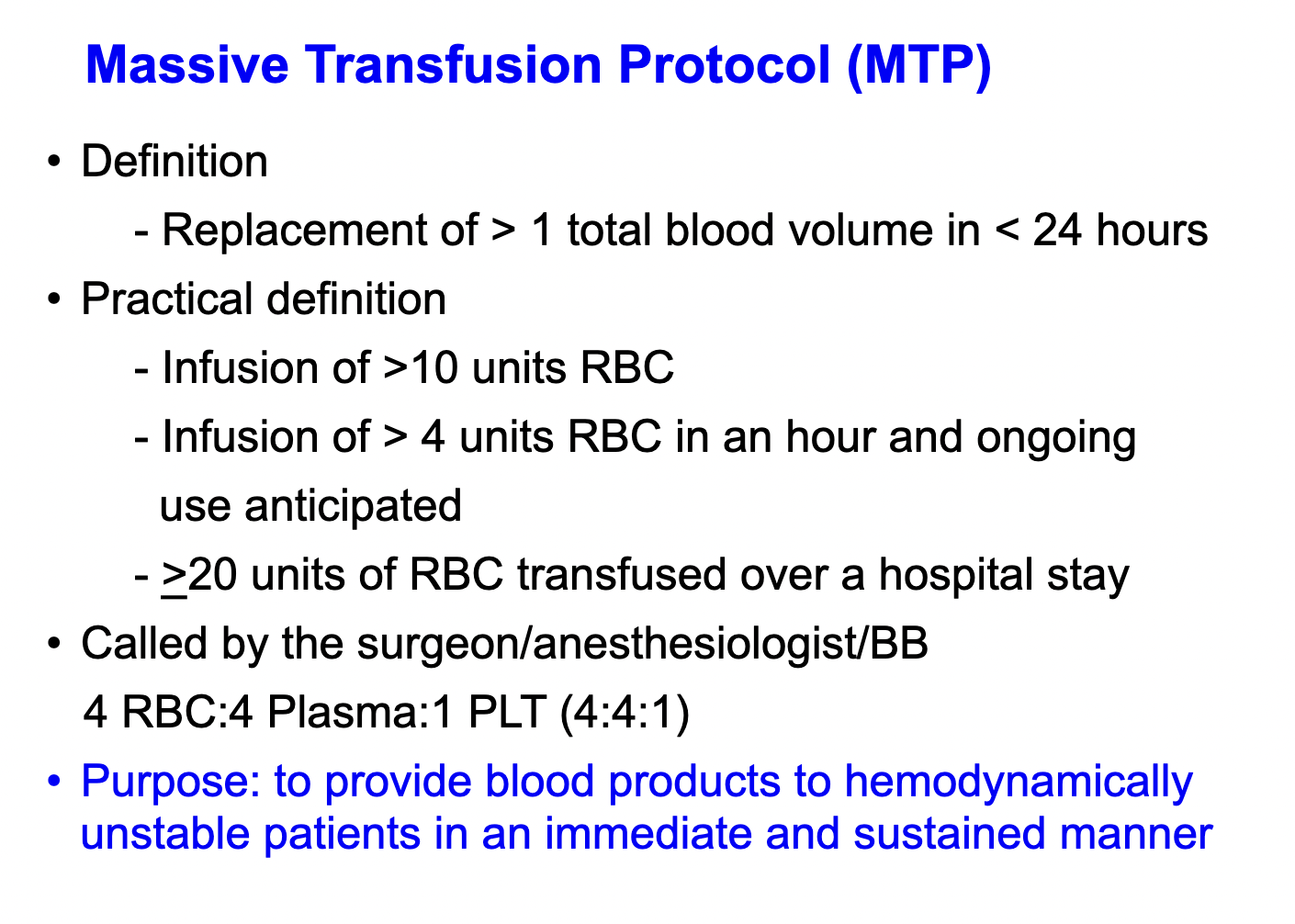

There are various definitions of what constitutes “massive transfusion” (eg, transfusion of more than 3 units of PRBCs in 1 h, or more than 10 units in 24 h). There are also several predictive scores that can be used to estimate the probability that a patient will require massive transfusion. They all center around the concept that a patient with a large, acute bleed will require transfusion of several units of blood products over a relatively short period. It is important to recognize this, as massive transfusion is associated with several specific complications that require monitoring, preventative measures, or correction.

Dilutional coagulopathy can occur when blood loss is replaced primarily with PRBCs or crystalloid fluids. For avoidance of development of dilutional coagulopathy, it is recommended that patients receive PRBCs, FFP, and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio during massive transfusion. This recommendation is extrapolated from the trauma literature and based on the report of the Pragmatic Randomized Optimal Plasma and Platelets Ratio (PROPPR) trial. While more studies are needed to determine optimal ratios and more accurate estimates of mortality benefit, especially in patients with nontraumatic massive hemorrhage, replacing platelets and plasma in addition to PRBCs has physiologic basis. Transfusion in 1:1:1 ratio should begin as soon as need for massive transfusion is identified and should not be delayed while waiting for blood test results. Though not given as an answer choice, this patient should receive platelets in addition to FFP. Importantly, the 1:1:1 nomenclature as it relates to platelets may vary by institution or in different parts of the world, because 1 unit of apheresis platelets (ie, most platelets transfused in the United States) is equivalent to approximately 4 to 6 units of random donor platelets. The 1:1:1 ratio refers to 1 unit of random donor platelets. This can also be expressed as a 4:4:1 to 6:6:1 ratio of PRBCs, FFP, and apheresis platelets, respectively.

CBC, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen levels should be monitored every few hours, even as treatment is ongoing, and management should be adjusted based on these laboratory results when they become available. Transfusion of FFP should not be withheld while awaiting laboratory results, especially when multiple units of PRBCs have already been transfused. Cryoprecipitate should be transfused when fibrinogen levels drop below 100 mg/dL (2.94 g/L). Viscoelastic assays (thromboelastography and rotational thromboelastography) are being increasingly used, when available.

Tranexamic acid inhibits fibrinolysis and has been shown to lower mortality in patients with trauma and massive transfusion requirements if given within 3 h of onset of bleeding. Similar survival benefit was demonstrated in patients with postpartum hemorrhage. However, in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (HALT-IT) failed to show mortality benefit from tranexamic acid and found increased risk of venous thrombotic events. Even as data on the use of tranexamic acid in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding are evolving, it does not have a stronger indication for use in this patient over FFP.

The use of crystalloid resuscitation in the management of massive hemorrhage and hemorrhagic shock is limited, and crystalloids should be minimized or avoided altogether. IV fluids can contribute to dilutional coagulopathy, can result in volume overload and edema (including pulmonary edema and abdominal compartment syndrome), and have been associated with prolonged ventilator requirements and delayed wound healing in patients with trauma.

Another approach to blood-product resuscitation is the early, preferential transfusion of fresh frozen plasma in patients with long transport times. The PAMPer trial was a pragmatic, multicenter, cluster-randomized, phase 3 superiority trial that compared the administration of thawed plasma with standard-care resuscitation with 2 units of PRBCs by prospectively randomizing prehospital teams to providing fresh frozen plasma first vs PRBCs and demonstrated a 30-day mortality benefit of 23% vs 33% (95% CI, -18.6% to -1.0%; P = ) in patients in acute hemorrhagic shock transported in air ambulances. Conversely, COMBAT, which was a pragmatic randomized controlled trial for prehospital plasma administration in patients in hemorrhagic shock in military settings, did not demonstrate a difference in 28-day survival. In short transport times and in acute care hospitals, early administration of plasma has not demonstrated benefit. The most benefit of plasma-first resuscitation is in patients with transport times greater than 20 min, civilian air transports, and blunt injury. No benefits of plasma-first resuscitation have been demonstrated in short transport times, penetrating trauma, or acute care hospitals (choice C is incorrect).

Patients with hemorrhagic shock and massive transfusion are at risk for acid-base disturbances. Shock and hypoperfusion can result in metabolic acidosis, while citrate in blood products is metabolized to bicarbonate and can cause alkalemia. Even when patients have metabolic acidosis, the use of sodium bicarbonate is controversial and not favored when the pH is above 7.2.1234567

Literature Notes

Links to this note

-

ibcc massive transfusion protocol

- related: massive transfusion protocol

-

hypocalcemia is common abnormality after massive transfusion

- related: Hematology, massive transfusion protocol

Footnotes

-

Dionne JC, Oczkowski SJW, Hunt BJ, et al; for ESICM Transfusion Taskforce and the GUIDE Group. Tranexamic acid in gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(3):e313-e319. PubMed ↩

-

HALT-IT Trial Collaborators. Effects of a high-dose 24-h infusion of tranexamic acid on death and thromboembolic events in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding (HALT-IT): an international randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1927-1936. PubMed ↩

-

Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al; PROPPR Study Group. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471-482. PubMed ↩

-

Jaber S, Paugam C, Futier E, et al; BICAR-ICU Study Group. Sodium bicarbonate therapy for patients with severe metabolic acidaemia in the intensive care unit (BICAR-ICU): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):31-40. PubMed ↩

-

Napolitano LM, Kurek S, Luchette FA, et al; American College of Critical Care Medicine of the Society of Critical Care Medicine; Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Workgroup. Clinical practice guideline: red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(12):3124-3157. PubMed ↩

-

Stanworth SJ, Dowling K, Curry N, et al; Transfusion Task Force of the British Society for Haematology. Haematological management of major haemorrhage: a British Society for Haematology Guideline. Br J Haematol. 2022;198(4):654-667. PubMed ↩