mycobactrium avium MAC

- related: Tuberculosis, Infectious Disease ID, Pulmonary Diseases

- tags: #pulmonology

Overview

- new bronchiectasis, nodules: females, no smoking hx.

- indolent, fatigue, malaise, dry cough,

- 2 AFB sputum

- bronchoscopy: 1 specimen

- can also be fibrocavitary : older males, smoking hx

- cavitation

- can mimick TB

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is a group of free-living nontuberculous mycobacteria that are ubiquitous in the environment. Humans acquire the organism primarily via inhalation of aerosolized municipal water, but transmission can also occur through contaminated soil, food, and animals (eg, birds).

Most healthy individuals exposed to MAC have little risk of infection. However, disseminated disease can occur in patients with severe immunodeficiency (eg, AIDS), and chronic pulmonary infections can occur in those with underlying lung disease or in nonsmoking women age >50.

Pulmonary MAC infection frequently occurs in non-HIV patients with underlying lung disease (e.g., cystic fibrosis, COPD, or alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency), but it can also occur in the absence of prior lung disease (e.g., hot tub lung).

Transmission

- Unlikely tuberculosis, human-to-human transmission is relatively rare.1

- There were cases of potential person-to-person transmission of other non-TB mycobacterium in CF patients at same clinic.2 3

- M. avium is ubiquitous in soil, drinking water, household plumbing

- Transmission happens with inhalation of aerosolized M. avium cells.4

Environmental Risks

- Peat-rich soils

- Natural waters and drinking waters

- Showerhead biofilms

- Spas

- Humidifier systems

- Household plumbing.4

Patient Risks

- M. avium is less pathogenic than TB and requires more host impairment

- Cystic fibrosis patients

- Patients with α-1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Transplant patients

- Patients with HIV

- Underlying Lung Disease

- Bronchiectasis

- Severe COPD

- Pneumoconiosis

- Prior TB, prior cavitary lung diseases

- Esophageal disorders: GERD, chronic aspiration.4

- Tall, thin, older women

- with scoliosis, mitral valve prolapse, pectus excavatum.

- Young, immunocompetent patients with hot tub exposure

- presents more like hypersensitivity pneumonitis.5

Symptoms

- Symptoms of MAC are nonspecific and include cough, fatigue, dyspnea, hemoptysis

- Fever and weight loss are less commmon

- Symptoms are usually slower onset due to more indolent nature of MAC (months to years).6

- disseminate

- B sx

- LAD

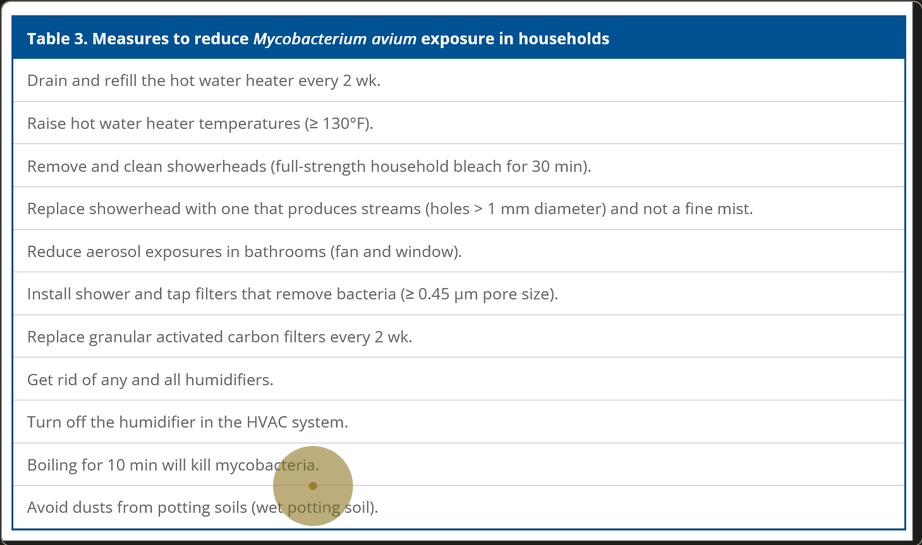

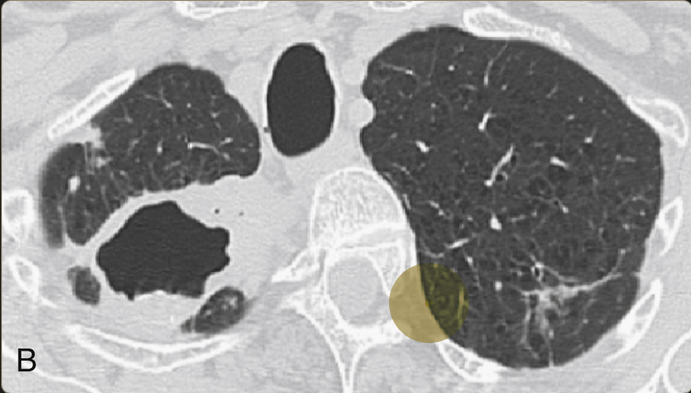

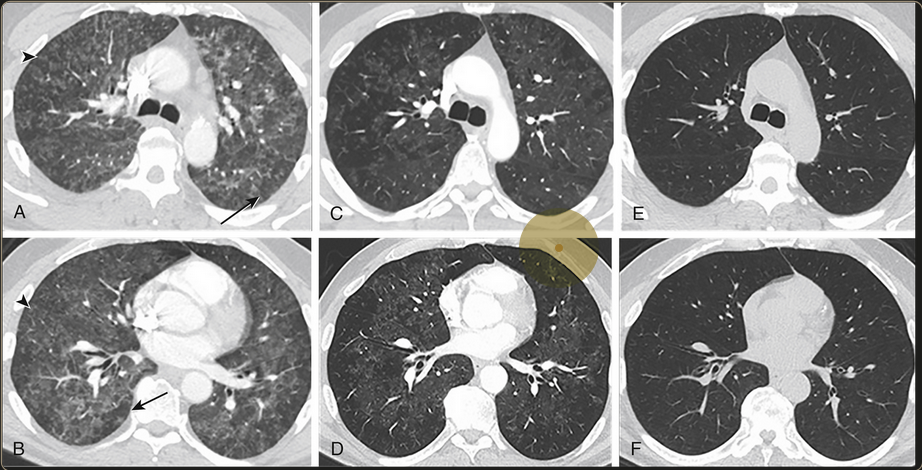

Images

Extensive cavitary lung destruction from untreated chronic MAC infection

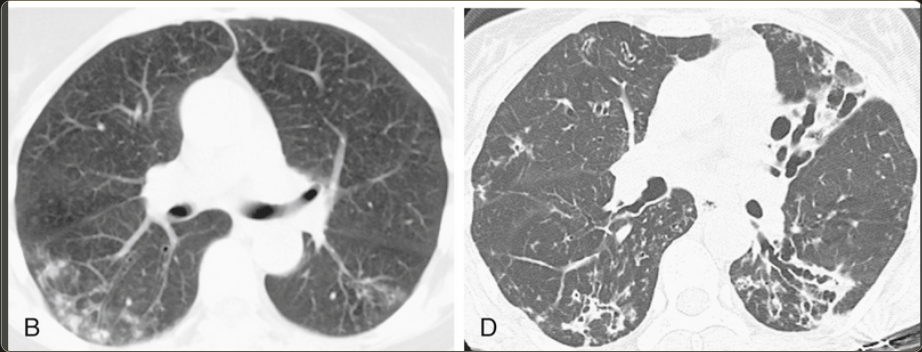

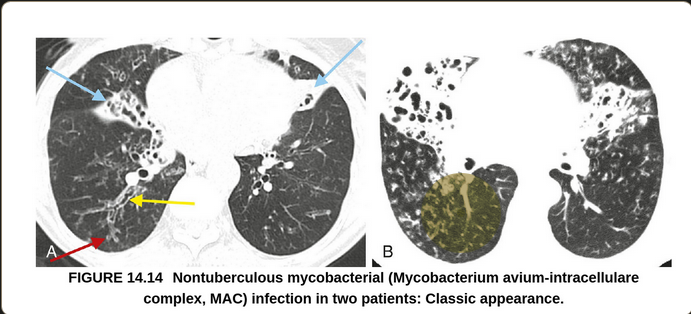

“…predominant feature is airways disease that predominates in the middle lobe and lingula. Bronchiectasis, airway wall thickening, and mucous impaction are typically present. Centrilobular nodules and TIB opacities are also frequently seen. There may be partial or complete collapse of the middle lobe and lingula in severe cases. In most cases, there is a relative paucity of consolidation present. This combination of HRCT abnormalities in an older woman is highly predictive of MAI (MAC) infection. The differential diagnosis includes recurrent bacterial infections or aspiration. ”7

Bilateral diffuse ground glass opacities with centrilobular nodular appearances

Diagnosis

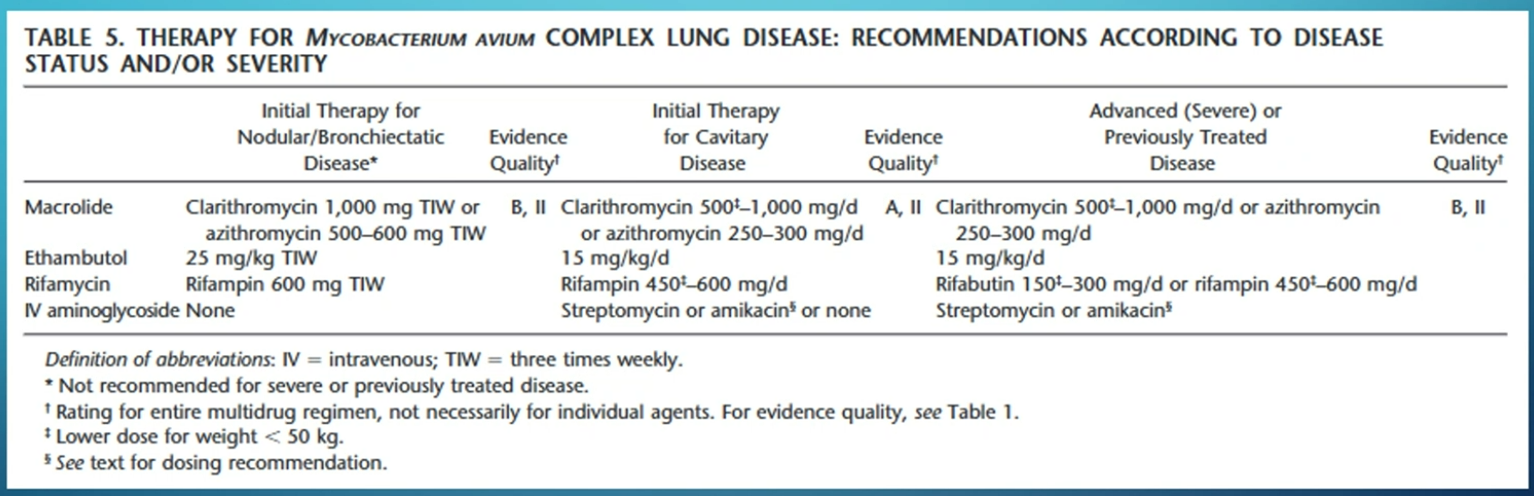

Treatment

- treatment: rifampin, ethambutol, azithromycin.

- INH is not used

- Treat for 1 year after sputum cultures are negative8

- testing sensitivity can be helpful to find a regimen without resistance (macrolide, amikacin)

- treat refractory MAC with amikacin

Treatment involves a combination of clarithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin for nodular/bronchiectatic MAC.

- new guideline: use IV upfront and inhaled if failed 6 months therapy vs triple therapy + inhaled if cavity

- CONVERT therapy: ALIS for failed 6 months triple abx 9

Links to this note

-

MAC infection can induce hypersensitivity pneumonitis in patients with exposure to hot tube water

- related: mycobactrium avium MAC

-

Diagnosis for MAC include AFB sputum for pulmonary disease and AFB blood for disseminated disease

- related: mycobactrium avium MAC

-

treat refractory MAC with amikacin

- related: mycobactrium avium MAC

-

CONVERT study found ALIS improved outcome in MAC patients after failed 6 months triple abx

- related: mycobactrium avium MAC

Footnotes

-

Broaddus, V. Courtney et al. Murray & Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Ed. V. Courtney Broaddus et al. Seventh edition. Philadelphia, PA, 2021. Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Aitken M.L., Limaye A., Pottinger P., et. al.: Respiratory outbreak of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense in a lung transplant and cystic fibrosis center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185: pp. 231-232. ↩

-

Bryant J.M., Grogono D.M., Greaves D., et. al.: Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2013; 381: pp. 1551-1560. ↩

-

Falkinham JO. Reducing Human Exposure to Mycobacterium avium. Annals ATS. 2013;10(4):378-382. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201301-013FR ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Broaddus, V. Courtney et al. Murray & Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Ed. V. Courtney Broaddus et al. Seventh edition. Philadelphia, PA, 2021. Print ↩

-

Infection with Mycobacterium avium complex in patients without predisposing conditions. Prince DS, Peterson DD, Steiner RM, Gottlieb JE, Scott R, Israel HL, Figueroa WG, Fish JE. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(13):863. ↩

-

Elicker, Brett M., W. Richard Webb, and W. Richard (Wayne Richard) Webb. Fundamentals of High-Resolution Lung CT: Common Findings, Common Patterns, Common Diseases, and Differential Diagnosis. Second edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Wolters Kluwer, 2019. ↩

-

An Official ATS/IDSA Statement: Diagnosis, Treatment, an Prevention of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases.” A Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007. ↩