Tuberculosis

- related: Infectious Disease ID, TB note 11 4, mycobactrium avium MAC, mycobacterium kansasii, rapid growsers, marinum, gordonae

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

Latent TB

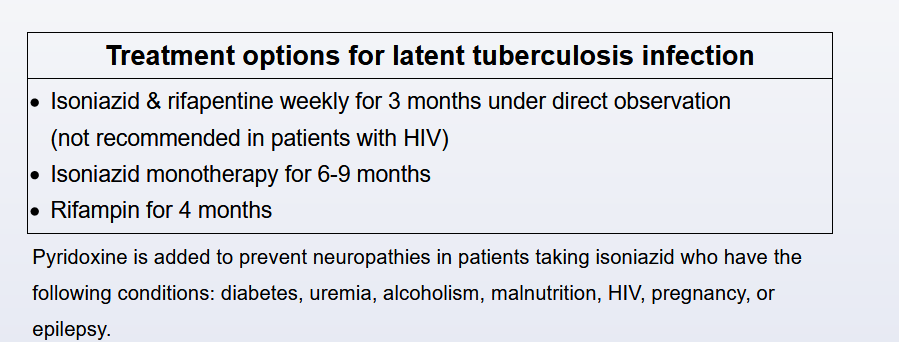

This patient has evidence of latent TB infection (LTBI) on the basis of the positive interferon-γ release assay; prior to beginning a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitor agent, LTBI treatment with rifampin for 4 months should be started. TNF-α inhibitors are now used in many inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and other seronegative spondyloarthropathies. These drugs increase the risk of active TB and fungal infections because of the inhibition of the TNF-α needed in the host response to cell immunity and the formation and function of the granulomatous response. All patients starting on these agents should be screened for LTBI, regardless of other risk factors, and treated accordingly. The recommended LTBI treatment has changed in the last iteration of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Thoracic Society guidelines, and the guidelines now recommend rifamycin-based regimens over isoniazid-based regimens, in general, for presumed drug-susceptible LTBI. The regimen options are 4 months of daily rifampin (4R), which is preferred; 3 months of daily isoniazid and rifampin; or 3 months of weekly isoniazid plus rifapentine. The guidelines recommend these regimens over the standard isoniazid for 6 to 9 months for reasons including efficacy, safety, and compliance with completion of treatment. In a direct comparison of 4R or rifamycin to 9 months of isoniazid, the 4R regimen was found to be associated with treatment completion in 79% vs 63%, and the 4R regimen was found to be noninferior for efficacy and had lower adverse events. Isoniazid monotherapy as compared with placebo is effective at reducing the incidence of active TB in the range of 60% to 90%, with good adherence, which is often difficult.

Before treatment initiation, a careful assessment to exclude active disease should be completed, including history; physical exam; chest imaging; and, if indicated, sputum assessment. The major toxicity of LTBI treatment is hepatotoxicity, including cholestasis and transaminitis, which is lower in those regimens containing rifamycin and higher in those using isoniazid. It should be noted that rifampin-containing regimens cause all secretions to have an orange-reddish coloration. Caution should be taken, and baseline liver function obtained, in patients with underlying liver disease or a history of significant alcohol use and in patients on other hepatotoxic medications. Generally, baseline liver function testing is also recommended during pregnancy.

Choice A is the recommended treatment for active TB, which would not be indicated in this patient with LTBI and negative sputum. Rifampin and pyrazinamide for 2 months was a previously recommended LTBI regimen, which was found to be associated with significant hepatotoxicity and is no longer recommended. Isoniazid for 9 months or even 6 months (not offered as a choice) could still be an acceptable option but is now less popular. While a granuloma alone would not warrant LTBI treatment, the fact that this patient is about to start disease-modulating therapy necessitates prophylaxis.

The goal of testing for LTBI is to identify those individuals with high risk of developing active TB and who would benefit from prophylaxis. Those patients needing TNF-α inhibitor agents are in this high-risk group and, thus, should be tested and treated. In one study, the incidence of active TB in patients receiving TNF blockers was 1.4/1,000. Other indications for LTBI therapy include patients in close contact with or exposure to an active TB case; users of illicit drugs; residents in congregate settings; health care workers; those with HIV infection; those immunosuppressed due to transplantation, chemotherapy, requiring corticosteroids, or cancers; those with renal failure on hemodialysis; those with diabetes; those with silicosis; patients with abnormal chest imaging consistent with TB with apical fibronodular changes but not including a granuloma; and, in the United States, immigrants from countries with a higher incidence of TB. Another high-risk group is patients converting from negative to positive on purified protein derivative or interferon-γ release assay. The timing of initiation of LTBI treatment in relation to beginning the anti-TNF drug can vary, but many now think they can be started concurrently. Older data suggested that LTBI treatment should begin a month prior to initiation of the anti-TNF drug regimen.

This patient’s clinical presentation is consistent with active pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), which is typically due to the reactivation of latent disease. Suspicion should be raised when individuals with epidemiologic risk factors for exposure (eg, substance abuse, homelessness, birth in a TB-endemic region) develop characteristic clinical manifestations (eg, fever, cough >2 weeks, weight loss).

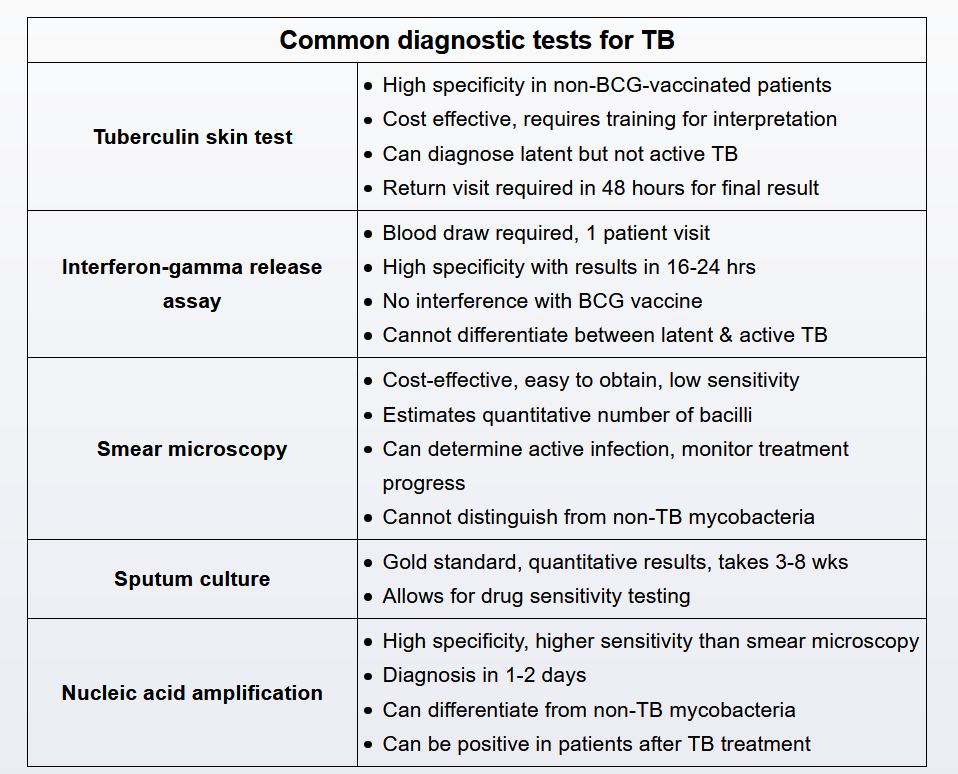

Diagnostic evaluation begins with chest x-ray to determine if there are signs of active disease such as upper lobe cavitation (70%-80%), hilar lymphadenopathy, or pleural effusion. Patients with suspicious x-ray findings are definitively diagnosed when Mycobacterium tuberculosis is isolated in body fluid or tissue (lung, pleura).

Sputum sampling provides the least invasive and costly route for microbial confirmation. Three single sputum samples (spontaneous or induced) are submitted in 8to 24-hour intervals with at least 1 early-morning sample. Sputum should be sent for acid-fast bacillus smear, mycobacterial culture, and nucleic acid amplification testing.

Although patients with suspected pulmonary TB should also undergo tuberculin skin testing or interferon-gamma release assay, these tests cannot distinguish between active and latent disease and are ordered primarily to support the diagnosis (positive test results suggest exposure)

Sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear is the most rapid, least expensive, and widely used diagnostic test for pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). However, this test cannot be used to definitively rule in/out the diagnosis due to:

- Low sensitivity (45%-80%) - microscopic detection of AFB requires a high burden of organisms (>10,000 bacilli/mL), so false negatives are common

- Poor differentiation - cannot distinguish between tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacterium (both are AFB positive), so confirmatory testing with mycobacterial culture or nucleic acid amplification (NAA) testing is required

Given this patient’s positive tuberculin skin testing (indicating likely Mycobacterium tuberculosis exposure) and characteristic TB risk factors and clinical manifestations, active pulmonary TB remains the most likely diagnosis. TB can be definitively established or excluded with one or both of the following:

- Mycobacterial culture - takes 2-6 weeks but is considered the gold standard for microbial confirmation and drug susceptibility

- NAA testing - highly sensitive (95%) and specific (98%), and results return rapidly (<48 hours); unlike AFB smears, NAA testing can distinguish between M tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria

TB pleural effusion

Latent TB

All health care personnel (HCP) should receive regular (eg, annual) screening for tuberculosis (TB) with a tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-gamma release assay. HCP who have a TST with >10-mm induration at 48 hours are likely to be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and should undergo a chest x-ray. Those with no chest x-ray abnormalities and no symptoms (eg, weight loss, night sweats, chronic cough) are considered to have latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI).

LTBI is noninfectious. LTBI screening should only be offered if treatment would be considered because, for most patients, the lifetime risk of advancing to active TB is small (5%-10%).

Latent TB treatment should be undertaken only if there are no symptoms or chest x-ray evidence of active TB.

Treatment (eg, 6-9 months of isoniazid) should be offered to affected individuals who are at higher risk of developing active TB (eg, immunosuppressed individuals) or those who reside (eg, inmates) or work (eg, HCP) in high-risk congregate settings.

Because LTBI is noninfectious, affected individuals, including HCP, may continue to work without restrictions (even if they decline or do not complete treatment); they do not require precautions (eg, N95 mask) or an absence for a full course of treatment (Choices C and D).

Miliary TB

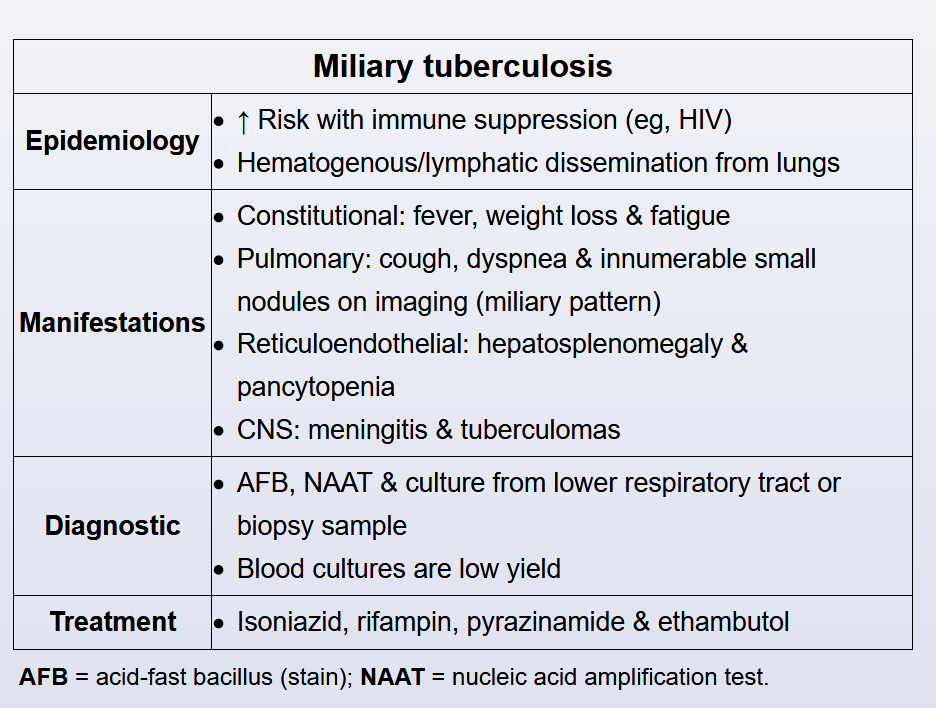

This patient with HIV and recent incarceration has subacute, nonspecific symptoms, pancytopenia, elevated transaminases, and a diffuse pulmonary infiltrate suggesting miliary tuberculosis (TB).

Miliary TB denotes the widespread hematogenous dissemination of Myobacterium tuberculosis from the lungs to multiple organs. Risk is significantly higher in patients with deficits in cell-mediated immunity (eg, HIV, tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors). Symptoms usually arise over weeks and include fever, night sweats, weight loss, weakness, cough, and dyspnea. Liver (eg, right upper quadrant pain, vomiting, transaminitis) and hematologic (eg, anemia, leukopenia, and/or thrombocytopenia) manifestations are common.

Miliary TB is classically associated with a diffuse nodular infiltrate on chest imaging. Diagnosis usually requires the identification of M tuberculosis by fluid culture or biopsy with culture; liver biopsy is generally considered to have the highest diagnostic yield, but bone marrow and transbronchial biopsies are sometimes performed. All patients should receive mycobacterial blood cultures, but diagnostic sensitivity is low.

Active TB

Active:

- RIPE: 4 drugs 2 months, and then 4 months INH/rifampin

- rifampin

- INH

- pyrazinamide

- ethambutol

- extend therapy if sputum clx positive after 2 months. Continue 7 months

- extrapulmonary: 9-12 months

MDR TB

- MDR if resistance to INH and rifampin

- extensively drug resistance: INH, R, fluoroquinolone, aminoglycoside

Links to this note

-

- related: Tuberculosis, Infectious Disease ID, Pulmonary Diseases

-

- related: pleural effusion, Tuberculosis

-

miliary TB finding includes diffuse nodules in random distribution

- related: Tuberculosis

-

- related: Tuberculosis

-

- related: Tuberculosis

-

- related: Tuberculosis

-

- related: Tuberculosis

-

- related: Tuberculosis

-

type 4 hypersensitivity reaction and TB testing

- related: Tuberculosis