constrictive bronchiolitis is small airway disease

- related: Pulmonology

- tags: #literature #pulmonology

This patient has developed rapidly progressive and irreversible obstructive lung physiology approximately 2 months after completion of chemotherapy. His clinical, radiographic, and histologic findings are consistent with the diagnosis of constrictive bronchiolitis (choice C is correct). Constrictive bronchiolitis, also termed “bronchiolitis obliterans” or “obliterative bronchiolitis,” is frequently used by clinicians to describe the clinical syndrome of dyspnea and airflow limitation not reversible with inhaled bronchodilators that is associated with small airways injury due to a spectrum of causes, such as inhalational exposure, infections, systemic diseases, and hematopoietic cell or lung transplantation. It has been advocated that the term “constrictive bronchiolitis” be used to describe the small airways disease in which variable narrowing or obliteration of the small airways occurs in a nonlung transplant patient, and the term “obliterative bronchiolitis” be applied only to describe the airway injury of chronic lung transplant rejection (so-called bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, or BOS).

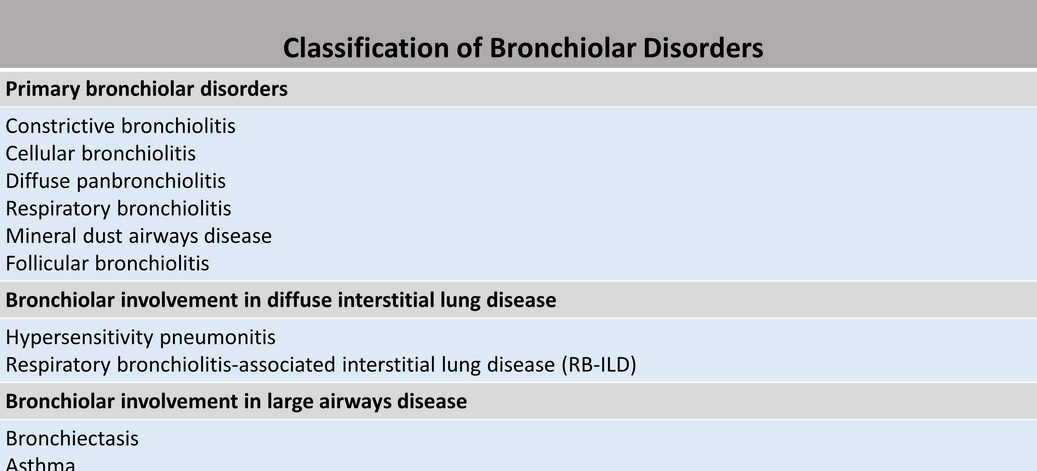

Small airways are defined as noncartilaginous airways with an internal diameter of less than 2 mm that are located from approximately the eighth generation of airways down to the terminal bronchioles and respiratory bronchioles. In normal patients, these small airways are not visible on CT due to their small size. However, in certain instances, these small airways may become visible due to underlying disease. Numerous classification systems have been used to describe small airways diseases based on clinical, imaging, and histologic findings. On a practical basis, small airways disease can be classified as follows: (1) Primary bronchiolar disorders, which includes constrictive bronchiolitis, cellular bronchiolitis, diffuse panbronchiolitis, respiratory bronchiolitis, mineral dust airways disease, and follicular bronchiolitis; (2) Bronchiolar involvement in diffuse interstitial lung disease, such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) and RB-ILD; and (3) Bronchiolar involvement in large airways disease, such as bronchiectasis or asthma (Figure 3).

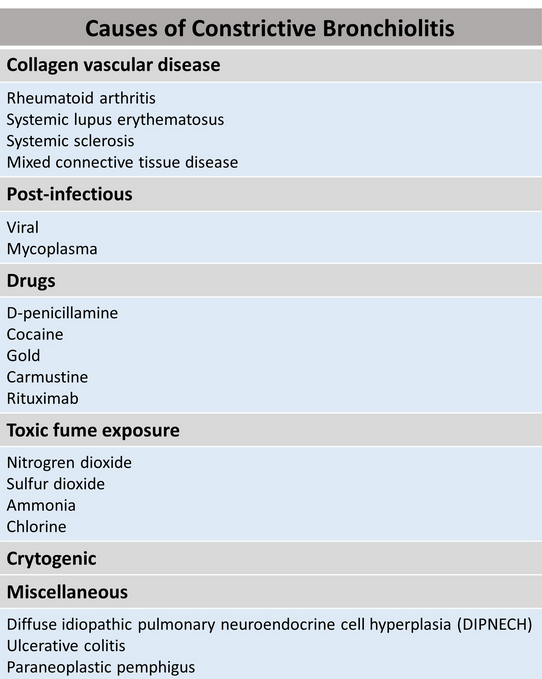

Constrictive bronchiolitis is associated with numerous predisposing conditions or causative agents (Figure 4). Constrictive bronchiolitis is rarely truly cryptogenic; most cases probably have an undisclosed precipitating cause or association, such as a connective tissue disease that subsequently declares itself. Although more commonly associated with BOOP, there have been a few report cases on constrictive bronchiolitis associated with rituximab use.

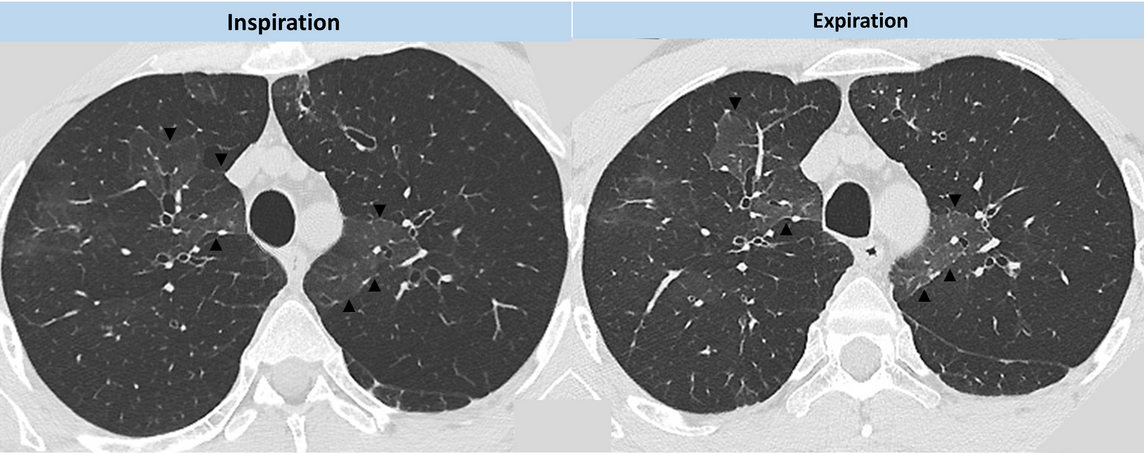

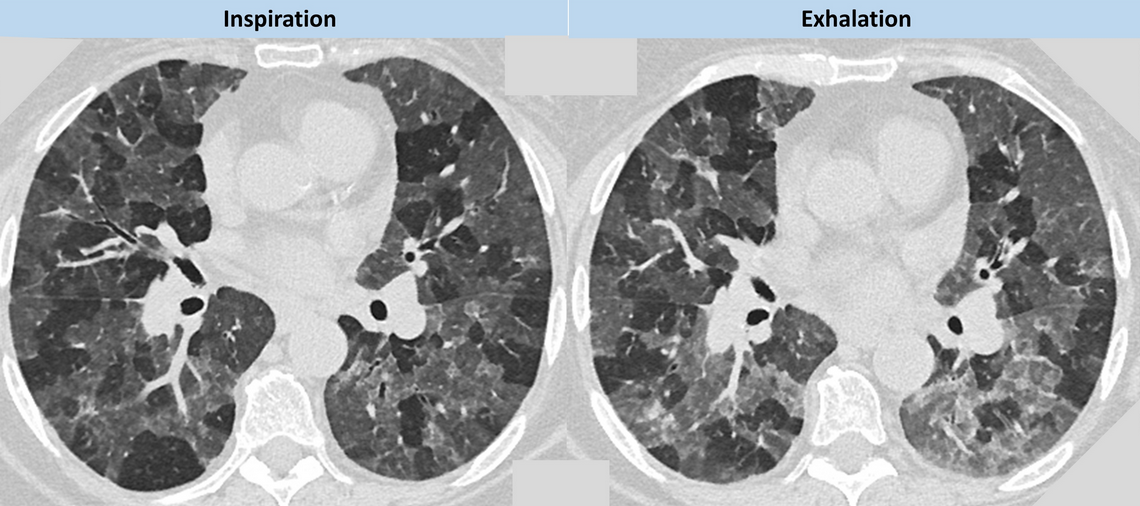

The plain radiographic features of constrictive bronchiolitis are nonspecific and absent in all but the most severe cases; the signs can be summarized as diminished pulmonary vasculature and overinflation of the lungs with or without bronchial wall thickening. CT signs of constrictive bronchiolitis comprise areas of reduced density of the lungs (mosaic attenuation pattern), constriction of the pulmonary vessels within areas of decreased lung density, bronchial abnormalities, and lack of change of cross-sectional area of affected parts of the lung on scans obtained at end-expiration. As noted in this patient, the mosaic attenuation pattern in constrictive bronchiolitis more commonly tends be subtle, although the regional inhomogeneity of lung density is clearly accentuated during expiration (Figure 5). Mosaic attenuation tends to be more pronounced when seen in conditions such as HP where the small airway disorder is part of parenchymal lung disease (Figure 6).

- CT images from our patient demonstrating the regional inhomogeneity of lung density being accentuated during expiration.

- CT images of a patient with HP demonstrating more pronounced mosaic attenuation which is being accentuated during expiration. Note the patchwork of secondary pulmonary lobules, giving a geographical outline to the interface between normal and abnormal lung.

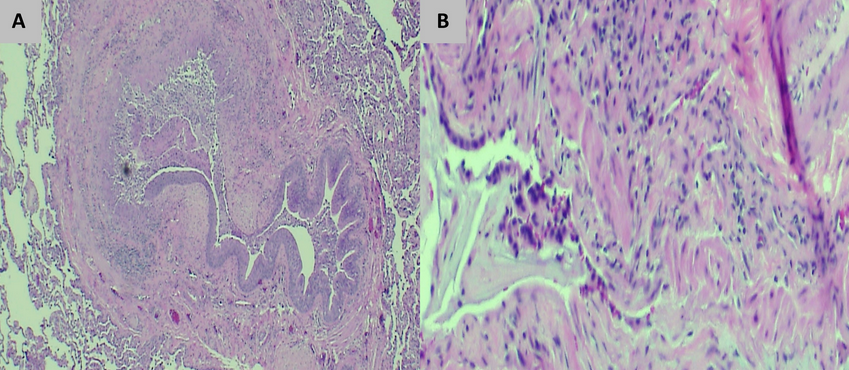

Constrictive bronchiolitis is a bronchiolar small airway disease that surrounds the lumen with fibrotic concentric narrowing and obliteration. This submucosal and peribronchiolar fibrosis leads to irreversible obstruction of the small airways. The lumen narrowing may range from slight and histologically subtle to marked, with complete obliteration of the bronchiolar lumen leaving only a residual fibrous scar (Figure 7).

- The lung biopsy specimen reveals a thick and fibrotic bronchiole characterized by fibrosis and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x10 magnification) shows a thick and fibrotic bronchiole with almost complete destruction of the lumen. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x40 magnification) shows the thick and fibrotic bronchiole with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

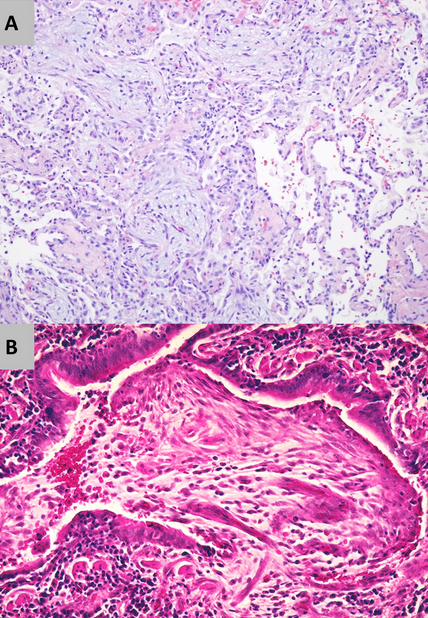

This patient’s clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic findings are not consistent with COP (choice A is incorrect). The patient lacks most of the cardinal symptoms of COP, such as cough, fevers, malaise and weight loss. Although gas exchange abnormalities are extremely common in COP, spirometry most commonly reveals mild to moderate restrictive ventilatory defects. A small percent of individuals with COP can develop obstructive ventilatory defects, though they do not tend to be severe. CT features of COP tend to comprise extensive air-space disease in the form of patchy lower lung zone predominant ground glass opacities and consolidation with a subpleural and/or peribronchial distribution (Figure 8). Histologic hallmarks of COP consistent of patchy organizing pneumonia with intraluminal fibrosis within bronchioles and airspaces. The endoluminal granulation tissue polyps are referred to as Masson bodies. There is often mild interstitial inflammatory infiltrate with type pneumatocyte II metaplasia (Figure 9).

- Lung histopathology of BOOP/COP: Patchy organizing pneumonia with intraluminal fibrosis within bronchioles and airspaces. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x10 magnification) shows homogenous interstitial inflammatory infiltrate with endoluminal granulation tissue. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x40 magnification) shows endoluminal granulation tissue polyps (Masson bodies).

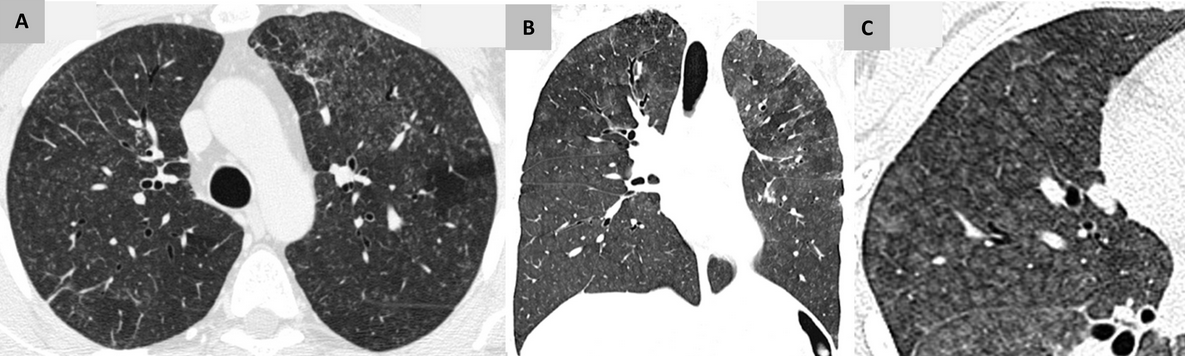

This patient’s clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic findings are also not consistent with HP (choice B is incorrect). Subacute HP would be the most plausible consideration though it is characterized by the gradual development of productive cough, dyspnea, fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss. Pulmonary physiologic testing is not specific and can demonstrate restriction or a mixed pattern of both obstructive and restrictive ventilatory abnormalities, as well as a reduction in diffusing capacity. CT findings of subacute HP most commonly consist of bilateral patchy and geographic areas of low attenuation with lobular sparing and diffuse centrilobular ground-glass nodules (Figure 10). The histopathologic features of HP are typically those of chronic inflammatory pneumonia and indistinct, poorly formed nonnecrotizing granulomas (Figure 11).

- Chest CT of subacute HP: shows bilateral patchy and geographic areas of low attenuation with lobular sparing and diffuse centrilobular ground-glass nodules. (A) Axial view. (B) Coronal view. (C) Magnified view highlighting the characteristic centrilobular ground-glass nodules.

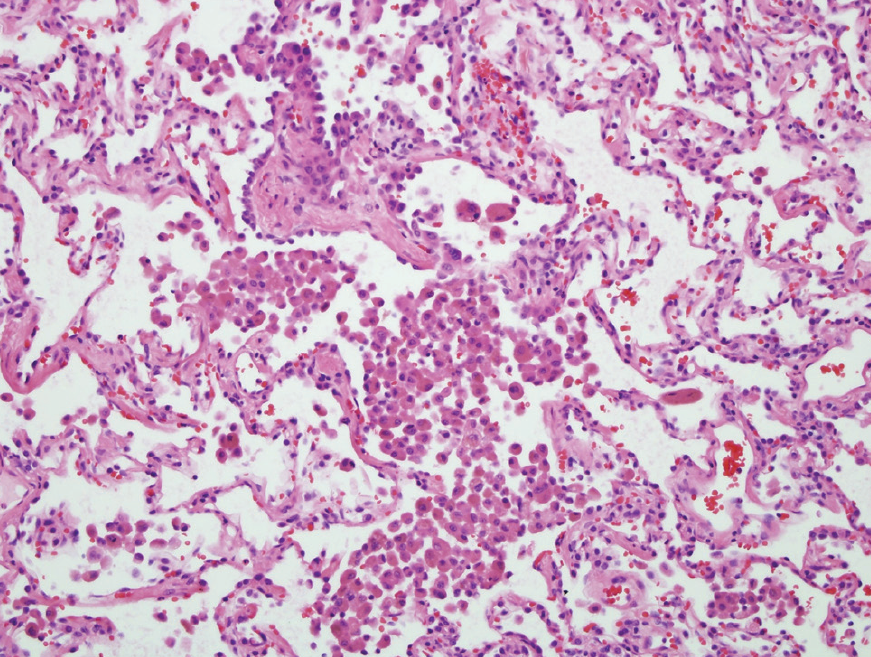

Lastly, this patient’s clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic findings are also not consistent with RB-ILD (choice D is incorrect). Virtually all patients with RB-ILD are current or former longtime cigarette smokers. Patients typically present with subacute symptoms of dyspnea, wheezing, cough, and sputum production. The most common pulmonary physiologic finding in RB-ILD is a mixed obstructive-restrictive pattern with mild-to-moderate reduction in diffusing capacity. Very similar to subacute HP, CT findings in RB-ILD commonly consist of patchy ground glass opacities, centrilobular nodules, and air trapping. The histopathologic hallmark of RB-ILD is the accumulation of tan-pigmented macrophages within the lumens respiratory bronchioles with associated submucosal and peribronchiolar infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 12).

- The lung biopsy specimen. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue (x10 magnification) showing pigmented macrophages within respiratory bronchioles with associated submucosal and peribronchiolar infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes.1

Links to this note

-

- Follicular bronchiolitis is a type of constrictive bronchiolitis (constrictive bronchiolitis is small airway disease).

-

- non-transplant and nonlung transplant patient: constrictive bronchiolitis is small airway disease

-

hydrogen sulfide is deadly sewer gas

- Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a colorless gas with a characteristic odor of rotten eggs and a common cause of inhalational toxic exposure in an occupational environment, especially in the petroleum industry. It may also be seen in confined spaces in which organic matter is being broken down anaerobically, such as in sewers and swamps. The clinical effects of H2S depend on its concentration and the duration of exposure. H2S has been referred to as “knock down gas” because inhalation of high concentrations can cause immediate loss of consciousness and death mechanistically by displacement of air or, in the case of confined space exposures, by asphyxiation. However, prolonged exposure to lower concentrations, such as 10 to 500 ppm, can cause various respiratory symptoms that range from rhinitis to acute respiratory failure and may also affect multiple organs, causing temporary or permanent dysfunction of the neurological, cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, or hematological systems. The findings in this case are consistent with exposure to H2S, including a history of an irritating odor (described as a “rotten eggs” smell) emanating from “sour” crude oil (ie, when the total sulfur level in the oil is more than 0.5%) at the transfer site with related symptoms and clinical findings, including a characteristic discoloration of the nail beds, a spirometric pattern consistent with likely bronchiolitis obliterans (mixed obstructive and restrictive) (constrictive bronchiolitis is small airway disease), and neuropathic changes (choice C is correct).